Background of 14th Amendment

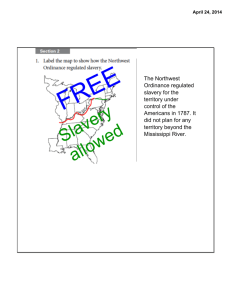

advertisement