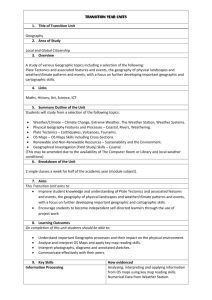

Harley J 1988

advertisement