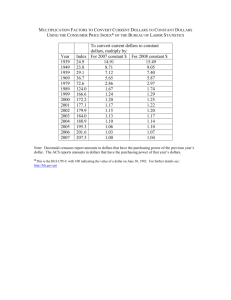

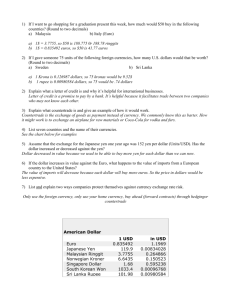

A straightforward explanation of the present financial

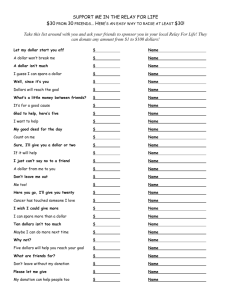

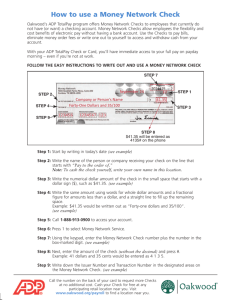

advertisement