The History of Pain - Indiana Pain Society

advertisement

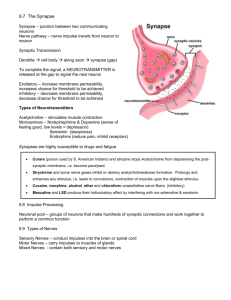

The History of Pain Michael L. Whitworth, MD What Is Pain? The word pain derives from the middle English word (circa 1250–1300 AD) peine meaning punishment, torture, pain. This word was derived from old French which was derived from the Latin poena meaning penalty, pain. This word was derived from the ancient Greek word poin meaning penalty . The English word pain was used in 1297 as "punishment," especially for a crime; also (c.1300) "condition one feels when hurt, opposite of pleasure," The earliest sense in English survives in phrase “on pain of death”. The verb meaning "to inflict pain" is first recorded c.1300. The methods used for punishment in order to produce death were also quite painful in the middle ages, and the word came to mean the same for the punishment and the physical effect of the punishment. But punishment, including torture, was commonly used as a remedy to many societal ills, transgressions against Christianity, and both civil and criminal behavior. The methods of torture used were gruesome and profoundly painful, therefore medieval torture and pain were synonymous. The church used torture during the Inquisition in order to extract confessions of sins and to ensure the non-believer became a Christian. The torture itself was not supposed to produce immediate death, unless a confession was acquired just before death. Each method of torture could be used only once, then another form of torture had to be employed, therefore there were an entire array of devices of torture created for this sacred purpose. Some of these methods are detailed in appendix A. The long unbroken history of this etymology of the word “pain” reflects a continuous uninterrupted understanding and usage reflecting the fact that all cultures throughout time have had to deal with pain. In the modern English language, its usage is commonly employed to designate both physical and emotional suffering, is used as a verb and a noun, and for the symptom of acute pain and the disease of chronic pain. Only through use in sentence context can one determine the appropriate meaning. Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) thought of pain as an emotion, like joy and Thomas More (1478-1535) stated pain is "the direct opposite of pleasure." Rene Descartes (1596-1650) perceived it as a sensation, like hot or cold and because of his perception of man as a machine (revolutionary for the time), also noted pain was a signal of physical pathology (Specificity Theory). Descarte defined pain as "Fast moving particles of fire ..the disturbance passes along the nerve filament until it reaches the brain..." Descartes (1664). Later, Dunglison (1846) defined pain as "a disagreeable sensation, which scarcely admits of definition" (this happens to be true today). Harris (1849) defined pain as the diminutive word "dolor." Mathison (1958) called pain "an emotion as vague as love, and as hard to define." The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in 1975 defined it as "an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage." This definition is a rather radical departure from the prevailing theory over the past 300 years: the Descarte Specificity Theory which viewed pain as stimulus-response. The IASP definition now invoked the use of emotion and also noted pain may not correlate with tissue damage. The departure from Descarte has become increasingly important with the recognition that whereas acute pain may be a symptom, chronic pain is actually a disease in itself. Pain may be acute (less than two weeks), subacute (less than 3 months but longer than 2 weeks), or chronic (longer than 3 months). The length of time pain lasts is not only important from the standpoint of different treatments being needed, but as pain becomes chronic there are actual changes that occur in the spinal cord independent of any tissue injury. Most acute pain is a symptom of tissue injury. Chronic pain however, may persists long after the tissue injury has resolved. But chronic pain may also be a mixture of tissue injury that is ongoing in addition to spinal cord neurological changes. Chronic pain is more closely related to that of a disease rather than a symptom. Acute pain is a symptom of tissue injury that involves some destruction of tissue, inflammation of the tissue, and the bodies attempt to repair the inflammation and tissue destruction. Chronic pain on the other hand, is more related to any of the chronic disease conditions including diabetes or hypothyroidism. Just as chronic disease states cannot be cured, usually chronic pain cannot be cured. However just as these other chronic conditions lend themselves to treatment, chronic pain may also be effectively treated but rarely is it eradicated. The gate theory of Wall and Melzack (1965) offers insight into the mechanisms of modification of pain by other incoming neurons and was the first break from Descarte in centuries. Emotion, especially anxiety and depression, prior history of response to pain, factors such as how your parents dealt with pain, cultural factors, sleep disturbance, etc. are but a few of the many factors that modify pain and amplify it as it moves along the spinal cord and brain. Chronic pain, the disease, consists of changes in the spinal cord itself that persists long after the inflammation of the acute pain is gone, or may open gates to amplify the remaining inflammatory response. Pain in the Literature Plato(428-348 B.C.) compared pain to pleasure in that when a person was suffering from acute pain, "...there is nothing pleasanter than to get rid of their pain." Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) on the other hand said, "Pain upsets and destroys the nature of the person who feels it." His concept of pain as a passion of the soul felt in the heart prevailed for almost twenty-three centuries. Not only was Aristotle’s view of pain influential on medicine for such a long period but so were his concepts of the humors of the body that were used as a basis for treatment into the mid 1800s. Lucretius (90-53 B.C.) said that "...atoms cannot ache with any pain or grief" and "...pain exists when violence attacks." Galen (A.D.129-199) was the first to recognize "referred pain" (pain felt in areas other than the affected part). He noted five different forms of sympathetic pain in his writings. Milton (1608-74) said "But pain is perfect miserie, the worst of evils..." (Paradise Lost), and Cervantes (1547-1616) noted in Don Quixote, "When the head aches, all the members partake of the pains." Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), observed "The art of life is the avoiding of pain”. He suffered from chronic migraine headaches. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-82) stated in his Natural History of Intellect, "He has seen but half the universe who never has been shown the house of Pain.". Music is full of expression of pain, both in words and in notes. Gustav Mahler exemplifies this in his second symphony, but Beethovan, Mozart, and virtually every great composer confronted and explored pain in their works. Some notable quotations about pain: “The pain of the mind is worse than the pain of the body” Publilius Syrus (Roman author, 1st century B.C.) “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” Pain and death are part of life. To reject them is to reject life itself.” Havelock Ellis (British psychologist and author 1859-1939) “Your pain is the breaking of the shell that encloses your understanding.” Kahlil Gibran (Lebanese born American philosophical Essayist, Novelist and Poet. 1883-1931) “Given the choice between the experience of pain and nothing, I would choose pain” William Faulkner “Pain is deeper than all thought; laughter is higher than all pain” Elbert Hubbard quotes (American editor, publisher and writer, 1856-1915) “If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself but to your own estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.” Marcus Aurelius (Roman emperor, best known for his Meditations on Stoic philosophy, AD 121-180) Pain is such an uncomfortable feeling that even a tiny amount of it is enough to ruin every enjoyment.” Will Rogers (American entertainer, famous for his pithy and homespun humour, 1879-1935) “We must embrace pain and burn it as fuel for our journey.” Kenji Miyazawa “Pain is temporary. It may last a minute, or an hour, or a day, or a year, but eventually it will subside and something else will take its place. If I quit, however, it lasts forever.” Lance Armstrong "We all must die. But if I can save someone from days of torture, that is what I feel is my great and ever new privilege. Pain is a more terrible lord of mankind than even death itself." ~ Albert Schweitzer, humanitarian, physician, theologian and composer Early History of Pain Primitive cultures and concepts Primitive humans, in spite of the lack of understanding of anatomy or physiology, had little difficulty in comprehending pain associated with injuries but were perplexed by pain caused by internal diseases or disorders. Externally visible cuts, contusions, or abrasions were readily understood causes of pain, whereas internal pain was thought to be due to demons. Early means to treatment of visible sources of pain or known injury were relegated to massage and the injured part, placing it in the cold water of a stream or lake, with placement of the injured area in the heat of the sun, and later using fire. Pressure was applied over the affected part and to diminish pain and over time primitive cultures learned to place pressure over specific regions that had a more pronounced effect although they did not know why. The cause of a painful disease or pain inflicted by a foreign object was thought to be due to evil spirits, pain demons, or magic fluids going into the body. Treatment consisted of eradicating the intriguing object or making efforts to appease or frighten away the pain demons. This was done with rings worn in the ears and nose talismans amulets Tiger claws and other charms. In some primitive societies the treatment was filled with activities in order to keep these evil spirits away from the body and therefore without pain. Spells and words of might were used by the injured man enabling him to cause the pain demons to flee from him. Pain, in early cultures, was thought to be the “sting of an evil spirit” that was initially treated by a sorceress-healer who is a representation of an incarnation of the Great Mother, while men began to assume the role of protector of the family. However even in patriarchal states the woman retained the preeminent role as healers. The sibyls and pythonesses of the ancients played formidable roles in the process of healing which included the power of exercising demons of illness and pain. The first sibyls (prophetess) was recorded in Greece in the 5th century BC with the most famous being the sibyl at Delphi. But later it was the medicine man that conjured up a changing of shape by dressing as an anti-demon, creating a special medicine hut house where he muttered incantations, and wrestled with pain demons. It is interesting that the power afforded the medicine man and special location of healing thousands of years later gave rise to the positions of power that doctors and hospitals hold in today's society. Some medicine man or shaman made small wounds for bloodletting and allowed that fluids or spirits or demons to escape in other societies the shaman physically sucked the spirit directly from the created wound, taking the evil spirit within himself and subsequently neutralizing it with magic. This is a therapy that continues to be used today in some countries. In some cultures, the medicine man was replaced by a priest, who was deemed a servant of the gods. Because human pain was thought to placate the deities, human sacrifices were made, and priests offered prayers in constructed shrines to appease the offended deities. These structures were known by different names throughout the ages such as ziggurats in the Babylonian and Assyrian cultures, pyramids in Egypt, temples in Greece, and teocallis in the Aztec cultures. Clay replicas of the painful body part were left in these temples for relief, and after a sacrifice was made to the gods, it was thought relief would be granted to the person suffering in pain. Prayers, exorcisms, and incantations are found on Babylonian clay tablets, in Egyptian papyri, and in Persian leathern documents, in carvings from Mycenae, and on parchment rolls from Troy. hhhhhh Ancient civilizations Ancient Egyptians believed pain other than that caused by wounds, was caused by religious influences of their gods or spirits of the dead. The spirits arrived at night and entered the body through the nostril or the ear. There were several demons and gods that were thought to inflict pain. The demon could depart through vomiting, urine, sneezing, or sweating of the limbs. It was believed there was a widely distributed network of vessels called “metu” that carried the breath of life and sensations to the heart. This was the beginning of the concept that the heart was a center of sensation, an idea that lasted more than 2000 years. In Babylonian medicine intrusion into the body by an object, whether by demons or natural means, was the cause of pain. The pain of dental caries was thought to be due to worms burrowing into the teeth. Pain and other medical knowledge was attributed in India to the god Indra. Budda in 500 B.C. believed the universality of pain in life was due to frustration of desires. It was noted, birth is attended with pain decay is painful, disease is painful, death is painful. Union with unpleasant is painful, painful and separation from the pleasant in any creating that is unsatisfied, that too is painful. Even though pain was recognized as a sensation, the Buddhist and Hindu focus on the emotional aspect of pain. The Hindus believe that pain was experienced in the heart which was considered to be the seat of consciousness. The practice of medicine in ancient China was codified in Huang Ti Nei Ching Su Wen, the Chinese canon of medicine written between the eighth and fifth centuries B.C. tracing its origin back to the time of the yellow Emperor who lived in 2600 B.C. The Chinese concept includes two opposing unifying forces, the Yin or the negative passive force, and the Yang a positive active force which are in balance and assist the energy call that Chi to circulate to all parts of the body via 14 channels or meridians, each connected to an internal organ. Pain exists due to an obstruction or deficiency or excess outpouring of the circulation of the Chi causing an imbalance in the yen and the yang. Acupuncture is thought to correct the imbalance through focusing on one of 365 points along the meridians. The Greek goddess of revenge, Poine, was sent to punish mortal men who dared anger the gods. The word pain may derive partially from the Poine. The culture of the Greeks seamlessly integrated belief in the gods and their interaction with man and exploration of the nature of man. The ancient Greeks were intensely interested in the nature of sensation in the sense organs of the body. Pythagoras traveled widely from Egypt to Babylon and to India, stimulated his disciple Alcmaeon, to study the senses. It was Alcmaeon that produce the idea that the brain, not the heart, was a center for sensation and reason. This view did not gain widespread acceptance in ancient Greek culture partially due to opposition from Aristotle for whom the heart reigns supreme. Anaxagoras who died in 428 B.C., believed all sensations were associated with pain, and the more the subject and object are unlike, the more intense the pain which was perceived in the brain. In contrast his contemporary Empedocles believes the capacity for all sensation especially pain and pleasure, was located in the heart's blood. Hippocrates believed pain was due to one of the four basic vital humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) being deficient or in excess and wrote of trepanation as a means of releasing the pain. He also used willow bark (contains salicylate) as an analgesic. Plato who died in 347 B.C. believed that sensation resulted from the movement of atoms communicating through the veins to the heart and liver which were the centers for appreciation of all sensation. The brain was thought of as an accessory organ in interpreting these sensations. Plato noted pain and pleasure were opposites, with the production of pleasure occurring on the elimination of pain. Aristotle who died in 322 B.C. elaborated further on Plato's concepts. He distinguished the five senses. For Aristotle the brain had no direct function in sensory processes for the heart was the center of all sensory perception. Aristotle believed the brains function was to produce cool secretions which cooled the hot air and blood arising from the heart. Pain was an increase in one of the 5 senses, especially touch. Pain was caused by excess of vital heat. Like touch, pain arose in the end organs of the flesh and was conveyed by blood to the heart. Aristotle's subsequent successors cast serious doubts on their masters views. However anatomical evidence that the brain was part of the nervous system was not demonstrated until 50 to 75 years later by Herophilus (335280 BC) and Erasistratus (310-250 BC). These philosophers noted that nerves attach to the spinal cord were two kinds: those for movement and those for feeling. The advances made that the Egyptians and Greeks were lost to Roman culture for four centuries until rescued by Galen (131-200 AD). Galen was educated in Greece and in Alexandria then subsequently came to Rome where he became the court physician to Marcus Aurelius. He studied the central and peripheral nervous systems, established the anatomy of the cranial and spinal nerves and a sympathetic systems. He defines three classes of nerves: soft nerves which had sensory functions, hard nerves which were concerned with motor function, and a third type related to the transmission of pain. Soft nerves were thought to contain invisible tubular structures in which a “psychic pneuma” flowed. Center in sensibility was the brain and received all kinds of sensations. Unfortunately the advances made by Galen were all but ignored until 1000 years later, and the concept promoted by Aristotle of the heart being the center of the sensorium prevailed for the next 1500 years. Herbal Medicine and Other Ancient Remedies For thousands of years, herbal medicine has been used throughout the world as a treatment for pain. Whereas the vast majority of treatments in ancient times were bogus or based on belief systems rather than effectiveness, some plants were effective in the treatment of pain. Plants such as hemp, henbane, poppy, and mandragora were all effective analgesics. A Babylonian clay tablet from 2250 B.C., describes a treatment for the relief of a toothache with powdered henbane seeds mixed with gum mastic. The Egyptian Ebers Papyrus mentions opium as a painkiller and the Hindu Charaka and Susruta, written about 1000 B.C., mention the use of wine and hemp fumes to produce "insensibility to pain." Socrates (470399 B.C.) took hemlock to relieve his pain and Hippocrates (460-379 B.C.) discusses belladonna, opium, mandragora, and jusquiam. Pliny (A.D. 23-79) described a mysterious "Stone of Memphis," which makes one "quite benumbed and insensible to pain." Theriac was a concoction of up to 64 substances, originally developed in the 1st century AD as an antidote to venomous snake bites and other poisonous animals. Ultimately its use spread throughout the world and was used for 1800 years in medical treatments for over 100 uses. It contained opium, myrrh, saffron, ginger, cinnamon, castor, hemp, as well as many other substances. Galen (A.D. 129-199) wrote on the use of the mandrake root as a painkiller and his writings with respect to both surgical and medical therapies, were esteemed for 1500 years virtually unchallenged. Pain control during surgery was difficult throughout the ages. Early Egyptians produced unconsciousness (and sometimes death) by progressively tapping with mallets on a wooden cap worn by the patient. Egyptian and Assyrian physicians performed surgical operations after compressing the carotid artery to induce unconsciousness. Egyptians used electric eel from the Nile and from the Mediterranean (the black torpedo fish) to produce analgesia by placing a live fish over the affected painful part. While effective, the treatment was also dangerous since selection of too large a fish could produce fatal electrocution. Similarly, the Greeks used the Mediterranean torpedo fish to deliver electrical treatments, especially as a treatment for headaches. The Chinese used mandrake wine to produce pain relief. In 1170, Roger of Salerno (Ruggiero Frugardi), mentions monks using sponges soaked in opium and held over the patient's nose for surgical procedures. A century later, Theodoric de Lucca (1205-96), referring to the same solution stated, "The patient may be cut and will feel nothing as if he were dead.”, however of course some actually did die. Alcohol has been used as a painkiller for many centuries. In Mexico, the agave plant was utilized as an anesthetic and Amazonians used caapi vine roots to deaden pain. The Australian Bushmen use duboisia tree leaves and in India the fruit of the java plum tree are used as painkillers. The East Indian pangiun tree is used as a narcotic and native Indians in North America used Dogwood (C. canadensis) bark to relieve pain; Hops (Humulus Lupulus) blossoms for earache or toothache; Speckled Alder (Alnus incana) twigs for headache and backache; Burdock (Arctium minus) leaves for rheumatic pains. Coca leaves are chewed by the South American Indians partially as a pain reducing agent. AmeriIndianas used “pain pipes” held against the skull, and mouth suction was applied to pull out the pain or illness. Moxibustion, as practiced by the Chinese, used a small cone of combustible plant material (usually wormwood) was laid on a prescribed point (as in acupuncture) and set afire. The pain of the blister acted as a counterirritant and the patient soon forgot the original ailment's pain. Moxibustion continues to exist today, but is used through heating of acupuncture needles rather than physically burning the skin. The Early Christian Period Because of the example of healing through laying on of hands by Jesus, the elimination of pain was thought possible in the early years of Christianity, and continuing on today the same reenactment of laying on of hands and by prayer by individuals and by the clergy exists. Faith and prayer in the early Church could turn every action into a remedy. Physicians have long held this type of intercession with high regard. One of the tasks that Jesus was to heal the sick and to banish pain and suffering. Consequently the Catholic Church place great stress upon the alleviation of pain by its clergy through prayer. Later, pain was considered a disciplinary measure for sinners, "good for the soul," and not to be the object of scientific scrutiny. It was perceived as a divine punishment and a continuous act of penance or contrition. Therefore, pain could be rationalized as a preview of what it meant to be damned. This view of pain was especially pervasive in certain arenas. Pain during childbirth was felt to be an accepted punishment and a duty for Original Sin until the mideighteen hundreds when Queen Victoria of England prevailed against church doctrine and accepted an anesthetic for childbirth. An unfortunate consequence of church dogma and doctrine was the belief that the deceased human body need remain intact, thereby preventing dissection of human bodies postmortem, and blocking advancement of the fields of an anatomy and physiology for 1500 years. The Dark Ages With the political destruction of Rome in 476 AD and the establishment of the Holy Roman empire, came a time where there were few advances in technology, literature, medicine, art, or in virtually any other realm. Europe disintegrated into a series of feudal states with very little commerce, travel, or cross-pollination with other cultures. There were multiple invasions, initially from the Goths, the Vikings, then the Muslims that kept Europe in chaos. Without strong state governments, the peoples of Europe found refuge in feudal barons and within the Church. The Church of the dark ages was frequently locally powerful but the Pope held little influence. The rise in feudal state power prevented consolidation with other feudal states, and the land barons preferred their independence. Money became much less important in a serf society, and education took on a decidedly back seat role. All secular learning was in preparation of studying the Bible. Great monasteries were constructed to provide a refuge for those that preferred to escape into a religious order. Recorded history, as had been so prominent in Rome and Greece, essentially ceased to exist for 800 years. Hand reproduction of copies of the Bible under the watchful eye of the monastic guides eclipsed, then finally supplanted history documentation or secular writings. The one bright spot in medicine in the Dark Ages, was at the very end of that period when Avicenna, the latin name for Ibn Sina, a Persian physician (980-1037 AD) , wrote a series of extraordinarily insightful treatises. The centerpiece of his works is the “Canon of Medicine” in which he combined his own insight with that of the writings of Galen, Indiana, and contemporary Moslem to formulate many modern medical philosophies including The Canon is a 1,000,000 word book that is considered the first pharmacopoeia and among other things, the book is known for the introduction of systematic experimentation and quantification into the study of physiology, the discovery of the contagious nature of infectious diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of contagious diseases, and the introduction of evidence-based medicine, experimental medicine, clinical trials, randomized controlled trials, efficacy tests, clinical pharmacology, neuropsychiatry, physiological psychology, risk factor analysis, and the idea of a syndrome. in the diagnosis of specific diseases. The importance of this man’s work cannot be underestimated as it guided medical schools and European medicine for the next 600 years. His influence is so profound he is known as the “Prince of Physicians”. He distinguished five external senses and five internal senses, and localized the internal senses to the cerebral ventricles. He describes 15 different types of pain due to different types of humoral changes and suggested methods of relief such as exercise, heat, and massage, in addition to the use of opium and other natural drugs. Avincenna was first to recognize pain as a discrete and separate sense. Avicenna wrote in the early eleventh century that "Nerves are one of the 'simple members' -- homogeneous, indivisible, the 'elementary tissues' (others include the bone, cartilage, tendons, ligaments, arteries, veins, membranes, and flesh)." He rendered an accurate physical description of them: "white, soft, pliant, difficult to tear." He and his contemporaries began to describe the complex and varied arrangements of nerves throughout the body, attempting to differentiate further their functions. In the Canon of Medicine, he observed: "Dryness in the nerves is the state which follows anger" suggesting he believed the nerves to be entangled with and responsive to the emotions, yet another sign of their strong connections to the brain. The Middle Ages Contrary to the rather stagnant European middle ages, the Islamic middle ages fluorished in research, continuing the advances of Avicenna. Muslim physicians contributed significantly to the field of medicine including anatomy, pharmacology, pharmacy, physiology, and surgery. The Arabs were influenced by and subsequently expanded on works of Galen, Hippocrates, Sushruta, and Charaka. They adopted as a template for medical practice the systemic approach of medicine, that rapidly spread throughout the Arab Empire. In 1242 Ibn al-Nafis gave the first description of pulmonary and coronary circulation, develped the concept of metabolism, and developed new systems of physiology to replace Galenic systems while discrediting many erroneous theories based on the four humours. Mansur ibn Ilyas in 1390 wrote “Anatomy of the Body” that contained comrehensive diagrams of the body’s nervous system. There were over 2,000 drugs and medicines cited by the end of the 12th century. However, the Arab Empire was culturally and politically isolated from Europe during the middle ages, so advances in medicine happened much slower in Europe. The European middle ages were a time of consolidation of church power and expansion of influence into virtually every aspect of daily life. There were plentiful reminders of pain in the art embedded in the church depicting the suffering of Christ. The daily lives of the people was difficult with manual labor in an agrarian based society causing significant daily discomfort. The church was not always monolithic in its message about pain with a divergence developing in the self flagillation and suffering of the Franciscans in order to achieve a mystical path to knowledge compared to the more practical Dominicans that eschewed suffering and pain as it interfered with the intellectual pathway to knowledge and the ability to study. However, folk medicine largely replaced the advances of ancient medicine for most of the population, yet medical knowledge was preserved and practiced in monastic institutions where the books of learning were housed. Organized professional medicine did not begin to re-emerge until the Schola Medica Salemitana in Salerno Italy was established in the 11th century. This institution along with Monte Cassino translated many Byzantine and Arabic works. Later, the great universities of the 13th century, Paris, Montpellier, and Bologna, had accepted medicine as one of the four pillars of learning, therefore became very influential in European medical treatment. The centrality of pain in the Christian definition of what it meant to be human, notably Adam's suffering after the Fall and Christ's humanity as defined by his physical suffering, was also accepted by the 1300 AD European universities of the time. The textbooks used in these universities were newly translated Latin works of Aristotle, Galen, and Avicenna used to teach the students of the arts that pain was at the very core of the definition of humankind as a living animal. Works from a medical tradition, such as the Hippocratic “On the Nature of Man”, were also used to show that pain was a defining human characteristic. However, pain, then as now, also presented practical issues- namely how to treat pain. The legitimacy of the university system hinged upon the search of the medical schools to provide a theoretical and practical response to the pain complaints of the patients. The Universities were rich with books by Aristotle on logic and philosophy, and also added new works by Galen on pathology and pain. Academic discussions about the causation of pain led to the conclusion that it could be caused by an “imbalance of the normal complexion of the individual”, ie. An imbalance in the four humours (blood, phlegm, bile, and black bile). These humours were thought to be carriers of the four qualities, heat, cold, dryness, humidity, that characterized the four elements that made up the human body, earth, water, air, and fire. Pain was reasoned to appear if the humours were in imbalance, even in one body part. The character of the pain depended both on the affected part and on the specific imbalance. A “weighty” pain was always due to the internal organs whereas a gnawing pain represented an abundance of a “biting substance” Within this medical model, pain could also be caused by a break in the continuity of the body, internal or external. The middle ages Universities gave substantial deference to the writings of the ancients more than the experience of the practitioner in making a diagnosis, determining prognosis, or the delivery of therapeutic advice. However, the patient’s reflections on their pain were recorded and compendiums of pain patterns from these reflections was integrated into the medical lexicon of the time. Taddeo Alderotti (1223-c.1295), medical master at Bologna, studied written medical testimonies to ask why mentally ill people did not always perceive pain and whether a large pain could conceal a smaller one. The experience of pain in childbirth was given more weight than a biblical curse by Bartholomew of Varignana (c.1260-p.1321) and Dino del Garbo (d.1327), both who practiced and taught medicine in Italy. Arnald of Vilanova (d.1311) who taught at Montpellier, advised in his Mirror of Medicine that the patient's account of pain was relevant in making a good diagnosis. For most medical authors, the main reason to study pain was to develop a tool for a better diagnosis of internal diseases. This was, for example, the aim of the complex classification of pain into 15 different types developed by the master Pietro d'Abano (c.1250-c.1316) from the University of Padua. According to Pietro, a pain could be throbbing, dull, stabbing, distending, pressing, vibrating or shaking, piercing, gnawing, nailing, crushing, grappling, freezing, itching, harsh or loose. In the treatment of pain, opium was well known to university trained and non-university trained healers alike. Physicians and apothecaries fought to control the market of narcotics. The use of ice as a local painkiller was also advocated, and was thought to work in the same way as opiates. However, they were not considered first-choice painkillers on theoretical grounds because they did not attempt to eliminate the cause of pain: they only masked its perception. The extent of narcotics use during this time period is difficult to establish. Common therapeutic devices that aimed to eliminate the cause of pain by restoring the humoral balance were more likely to have been used. In this respect, pain was just another ailment that would benefit from bloodletting, laxatives, purgatives and the monitoring of food, drink and sleep. Other remedies, such as astrological seals, were thought of as being useful as painkillers because they conveyed some specific properties explained by a magical rationality. In extreme juxtapositioning to the University healers studying pain, the Inquisition or “Holy Office” began on the road to sanctioned torture under Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) when he ordered members of his church to prosecute heretics. Previously heretics had their property confiscated, however under the Inquisition, heretics were tortured, burned to death, or submitted to combinations of torment resulting in death. Torture was used as a way to submit the heretics to a taste of hell, and at the last minute they would repent, although sometimes too late to save their physical bodies. Inventiveness rose to new heights during the Inquisition with a multitude of methods devised to inflict the maximum amount of pain. Appendix A. lists some of these gruesome methods. The last victim of Inquisition was put to death in 1826, thereby closing the door on a horrible ethnic of Christian history. Unfortunately, torture became so commonly employed in society that it was used to settle differences and punish criminals in addition to being used as a method to save the souls of those that were lost. The only other significant advance occurring in pain management in the Middle Ages was a gradual shift in understanding of the location of the center of sensory perception from heart to the brain. Albertus Magnus localized the sensory source to the anterior cerebral ventricle of the brain in 1254 AD and made extensive study and commentary of the works of both Aristotle and Avicenna. Mondino de’Liucci presented a bizarre overlapping of Aristotle and Galenic thought in his year 1316 unillustrated anatomy book Anathomia Mondini that served as a textbook for over 200 years in many European medical schools. During the middle ages the population was occupied in for centuries with the recurring Black Death, which further cause contraction of travel for fear of contagion. 25 million people died of the plague is about one third of Europe's population. Also during the middle ages, the painful disease syphilis became quite prominent. It was known the French disease, and cause pain is so severe that the sufferers felt they had been beaten with sticks. The Renaissance Prior to the Renaissance, it was thought pain existed outside the body as a punishment from god. The torture inflicted during the most egregious aspects of the Inquisition did nothing to change that view and in fact encourged it. The only relief from pain was to be through prayer and through confession (frequently just before death mercifully removed the pain from the tortured). The treatments available during the Renaissance included electrical therapy developed from electrostatic generators (batteries and other electrical generation had not yet been invented). Massage, exercise, use of natural herbs including opium (not commonly available) were used to treat pain. This was a period of great scientific interest with advances being made in physics, physiology, anatomy, and chemistry. Plato's and Aristotle's works were studied in particular from the Greek originals, and not translations as had been done throughout the middle ages. The fall of Constantinople in 1453 opened up massive libraries of ancient works that bridged continents and cultures. One of the most famous academies of learning was the Academia Platonica founded in Florence Italy by Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492). Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was one of the greatest scientists and artists of the era. His early drawings were inaccurate based on descriptions of dissections from the middle ages, but later he began performing dissections himself when the ban against human dissection was lifted by Pope Sixtus IV in the 1470s. Subsequently the accuracy of depiction of the human body (especially the muscles) improved markedly. These drawings also were a prelude to the further study of physiology of muscles. He considered nerves as tubular structures and pain sensibility was strictly related to touch. The sensorium source was located in the third ventricle of the brain and the spinal cord was thought of as a conductor that transmitted signals to the brain. Da Vinci made wax castings of the ventricles of the br ain as part of his work. Bartolemeo Eustachi (1520-1574) was an anatomist that was one of the first in the Renaissance era to illustrate the entire nervous system intact as seen in the drawing on the next page. The anatomist Vesalius in 1543 further expanded on Leonardo da Vinci's concepts and his works, the brain was considered the center of sensation. This period saw an explosion of the understanding of anatomy of the human body, but studies on physiology would have to await scientific advances in the 17th century with electricity and magnetism and pneumatics that were necessary to further define concepts of pain and nerve transmission. In the Renaissance, there were only a few effective drugs employed: opium and quinine. Seventeenth Century Aristotle's concept of the heart as the source of pain was alive and well in the 1700s. William Harvey in the year 1628 discovered the circulation of blood believed the heart was where pain is experienced. René Decarte (1596-1650) did extensive anatomical studies including sensory physiology. He believed that nerves contained a large number of fine threads that for the marrow of the nerves and connect the brain with the nerve endings in skin and tissues. Descarte was the first to separate the body from the soul by reducing a human being to a mechanical apparatus. This concept led to the modern view that pain is not inevitable and as a result of original sin, but rather is a result of the dysfunction in a mechanical apparatus. His famous drawing in the year 1664 demonstrated clearly the precursor to specificity theory that was not published until 1835. Descartes proposed his theory by presenting an image of a man's hand being struck by a hammer. In between the hand and the brain, Descartes described a hollow tube with a cord beginning at the hand and ending at a bell located in the brain. The blow of the hammer would induce pain in the hand, which would pull the cord in the hand and cause the bell located in the brain to ring, indicating that the brain had received the painful message. Based on this theory, researchers began to pursue physical treatments such as cutting specific pain fibers to prevent the painful signal from cascading to the brain. Also in 1664, Thomas Willis, a physician and professor at Oxford University, coined the term “neurology” in his textbook Cerebri anatome which is considered the foundation of neuroanatomy. Eighteenth Century The 18th century was a time of continued scientific exploration in Europe. With the societal infrastructure still in development in America in a very agrarian society, there was not much scientific advancement (with a few notable exceptions), and virtually no medical advancement in the New World. Theories of pain were slow to move throughout the scientific community and even slower throughout the very fragmented medical community internationally. In the first volume of his 1794 Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life, Erasmus Darwin supported the idea advanced in Plato's Timaeus, that pain is not a unique sensory modality, but an emotional state produced by stronger than normal stimuli such as intense light, pressure or temperature. Yet, there continued to be a lack of availability of tools to understand human neurophysiology and disease causation. European medical doctors adhered to the dogmas of vitalists, iatrochemists, and iatrophysicists. Each of these “brands” of medical practice had followers and none were able to explain the ills of the human body. The practitioners and university centers alike thought the ills of the human bodies were due to maladjustment of the body’s system. Diagnosis of illness was based on the four humours of Aristotle, bodily “tension”, or other even cruder doctrines. The Aristotle doctrine acceptance led to “bleeding” of the body or use of leeches to cure illness was common in the 18th century. Combining this with use of the drugs used in Europe (most of which were quite toxic or were patent medicines), and the lack of sterility, there was a healthy fear of being treated by a doctor. In America, herbal medicine was frequently used including witch-hazel, ginseng, snakeroot, etc and many people grew their own herbal gardens for medicinal purposes. Most doctors were self trained in America or trained as an apprentice with only relatively few doctors having been trained in the European institutions since the first US medical school was not established until 1765 at the University of Pennsylvania. Patent medicines began arriving from Europe into North America, carried over by settlers. These included Daffy's Elixir Salutis for "colic and griping," Dr. Bateman's Pectoral Drops, and John Hooper's Female Pills representing some of the first English patent medicines to arrive in North America. The medicines were sold by postmasters, goldsmiths, grocers, tailors and other local merchants. The development of electricity and magnetism moved slowly throughout the century but provided the foundation for both the understanding of neural transmission and pain perception. Stephen Gray in 1729 described static electricity conduction over metal filaments and classified materials as insulators or conductors; DuFay described positive and negative electricity in 1733, and the Leyden jar (the first capacitor to store electricity) was created in 1745. In 1744, Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein made the first experiment to determine the effects of electricity upon the human body. He found “the action of the heart was accelerated, the circulation was increased, and that muscles were made to contract by the discharge.” Subsequently he began to administer electricity for the treatment of certain diseases, finding it to be particularly useful in rheumatic diseases and palsies. From 1756 to 1791, John Wesley, an itinerate preacher in England, acquired his own friction electricity generators and leyden jars, and became an expert in the treatment of many diseases with electricity. Of note is that he kept copious notes on the results of treatments, both the successes and failures, that laid the foundation for electrotherapy treatment of pain and other conditions for centuries into the future. John Wesley also purchased scores of the static electricity generators and donated them to clinics for medical treatment he had established. From 1760-1780, static electricity was becoming better accepted as a treatment and was incorporated into European hospital treatments. However by 1800, the public had become skeptical of many of the offered treatments since they were being rendered by flim flam artists and charlatans claiming cures for a variety of conditions including pain. In the US, a Yale trained and degreed medical doctor, Elisha Perkins, invented electric metallic tractors which he claimed would cure many diseases by simply rubbing these across the skin. These became wildly popular in Europe and the US. In 1800 he was demonstrated to be a fraud by John Haygarth who did a parallel control test with painted wooden otherwise identical tractors and found no difference in the results, thus ushering in the beginnings of controlled studies. Other significant advancements of the century include the discovery of oxygen and nitrous oxide by Josph Priestly in 1774 and in 1799 Humphry Davy discovered the anesthetic properties of nitrous oxide. Nineteenth Century The concept of pain in the 19th century was in flux throughout the century, primarily due to changing views of society on religion, hell, and the purpose of pain. Early in the century, the predominate view of pain as a punishment still prevailed in the public eye. However by mid century, Darwin published “The Origin of Species” that was in itself controversial, but was extremely provocative, calling into question some of the fundamental principles of church dogma. There were a series of letters and responses in the journal Lancet in mid century to late century questioning the function of pain but also calling into question the religious presupposition for the need of pain. The concept of hell among the public was changing from a literal place with eternal damnation requiring everlasting pain to a figurative hell or that there is no need for further punishment once a person is already in hell. This change in view caused fewer people to believe in an external God driven pain as punishment and rather that there must be some other (medical) explanation for pain. Therefore, a medical explanation for pain was more widely accepted than a religious one by the end of the century than at it’s beginning, especially in England. The medical community in America was not held in high esteem during the 19th century, and in fact was frequently overtly deleterious to patient health early in the century. The continued application of the four humours to patients with subsequent treatments such as bleeding of a patient, use of purgatives in those already having diarrhea, or giving morphine for those in shock, made the profession of medicine so dangerous by the end of the 1830s that several states began delicensing physicians and the medical profession. People needing medical attention would not necessarily turn to an actual physician, of which few were available in rural areas. They may have preferred to be treated by a local or Amish healer, a patent medicine-maker, or a midwife. Doctors were simply tradesmen competing for clients against other tradesmen. Many doctors considered it part of their jobs to keep up a sophisticated social calendar and attract the kind of patients who could pay good money for their services. There was a proliferation of medical schools in America in the 1800s, but these were very unlike the University systems in Europe. These were effectively trade schools, frequently offering one year of education. By 1850 there were 52 medical schools in America compared to 3 in all of France. The quality of physician and inconsistencies in medical philosophies continued to cause erratic results at best, and a public highly suspicious of the training and expected outcomes of physician treatment. The American Medical Association was established in 1847 as an attempt to bring some standardization into medical training and practice, however it took more than a decade for these to be implemented. It was not until the 1880s that medicine was able to establish its credibility and convince legislatures of states that licensure of the profession was again warranted. The application of medical treatments made increasingly available throughout the century outstripped the scientific underpinnings of medical therapies, that had yet to be developed. Up to the 18th century all main textbooks of medicine contained the work of Hippocrates and Aristotle in which the heart was depicted as the sensory center. In the 19th century, the text books began to reflect an updated view of neurology, a field in its infancy. The anatomy texts continued to develop along with the primitive understanding of neurophysiology, and the textbooks before the 1870s often reflected bizarre anatomical constructs such as the assumption that blood would carry administered local anesthetics along the spine instead of spinal fluid. Those relying on these textbooks would institute treatments that had no merit but were actually dangerous. Corning, a neurologist in New York, performed the first epidural injection of local anesthetic in 1885 on this basis, believing that he needed to place the needle directly into the spinal cord in order for it to be effective. He aimed at the thoracic spinal cord but fortunately missed, and did not penetrate dura, since the 120mg cocaine he injected would have caused instant paralysis and probably death if injected either into the cord or into the spinal fluid. Instead, the patient developed a sensory block only from the waist down and Corning erroneously reported this as a spinal injection in the medical literature based on assumptions made by consulting an outdated anatomy textbook before the procedure. With the development of the battery (voltaic pile) by Faraday in 1800, new worlds of exploration of electricity, magnetism, and ultimately physiology were opened. The 19th century was an era of very rapid developments in these realms. An electrochemical telegraph (very slow) was developed by Campillo in 1809, Orsted discovered electric current produces a magnetic field, and the first galvanometer was invented in 1821. The electromagnet was invented in 1825 by Sturgeon and improved by Joseph Henry in 1828 by using several coils of wire. Electromagnetic induction was discovered in 1831, the first electromagnetic telegraph created in 1832 in Russia by Baron Schilling, and in 1835 the electrical relay was developed by Joseph Henry. The first practical battery was built in 1836 by Daniels and Cooke and Wheatstone in the UK and Samuael Morse in the US in 1838 independently developed the telegraph and codes. The lead acid battery (rechargeable) was created by Plante in France in 1859, the first dry cell battery by Gassner in 1887 (Zinc-carbon), and the first alkaline battery (NiCd) in 1899. Paralleling these scientific discoveries in electrophysics were medical advances. Charles Bell described the motor function of the ventral root and sensory function of the dorsal root in 1811, later confirmed by Magendie in 1822. In 1823 Sarlandiere in France introduced electroacupuncture and Magendie in 1826 used platinum needles inserted into muscles, nerves, and through the eye to the optic nerve for electrostimulation therapy in humans. Duchenne invented cutaneous electrical stimulation pads for electrical treatment in 1833, thereby bypassing the need to place needles into the tissue. This was a precurser of the TENS units of the mid 20th century. He found using a chopped DC current produced a more comfortable and warming sensation to patients. He also developed motor stimulation points for activation of specific muscles. A portable hand cranked electromagneto was invented in 1854 delivering mild shocks for the treatment of virtually anything. Julius Altheus, a British physician, became a champion of electroanalgesia in 1855 and wrote many books on the use of interrupted current on peripheral nerves (TENS) and more importantly developed scientific method as applied to clinical medicine (prior to this anecdotes by physician were given supreme weight in determining effectiveness). During the 1800s Winslow and others (Charles Bell described the motor function of the ventral root and sensory function of the dorsal root in 1811, later confirmed by Magendie in 1822), defined the anatomy and some of the physiology of the sympathetic nervous system. The age of exploration of microscopic structures was also found in the 19th century. Purkinje (Purkinje cell), Schwann (myelin sheath), Remak (unmyelinated nerve), Ranvier (nodes) all made important discoveries during that time. Staining methods advanced through the work of Joseph Gerlach in 1858 who was the founder of staining techniques….he used carmine as a stain. Weigert, Nissl, and Bielschowsky were major contributors to staining techniques in the 19th century. Neuroanatomy techniques were developed by Augustus Waller (1816-1870) Wallerian degeneration, Wilhelm His (1831-1904) histogenesis of the nervous system, Paul Fleschig (1847-1929) myelogenetic study of the nervous system. Mechanical sensors were discovered by Meissner, Paccini, Merkle, and Golgi during this time. SPECIFICITY THEORY The prelude to the specificity theory was a drawing of Descarte in the 17th century, however was not published in the current form until Muller. The law of specific nerve energies (specificity theory) was developed by Johannes Muller in 1835 and was expressed: ". . . (T)he same cause, such as electricity, can simultaneously affect all sensory organs, since they are all sensitive to it; and yet, every sensory nerve reacts to it differently; one nerve perceives it as light, another hears its sound, another one smells it; another tastes the electricity, and another one feels it as pain and shock. One nerve perceives a luminous picture through mechanical irritation, another one hears it as buzzing, another one senses it as pain. . . He who feels compelled to consider the consequences of these facts cannot but realize that the specific sensibility of nerves for certain impressions is not enough, since all nerves are sensitive to the same cause but react to the same cause in different ways. . . (S)ensation is not the conduction of a quality or state of external bodies to consciousness, but the conduction of a quality or state of our nerves to consciousness, excited by an external cause." Effectively, the theory stated pain is a specific sensation with his own sensory apparatus independent of touch and other senses. It had been suggested by Galen, Avicenna, and Descarte, and in 1853 by Loetze. In 1858, the theory was proven by Schiff after analgesic experiments on animals. After creating a series of lesions through the spinal cord he noticed that touch and pain were independent. Sectioning of the gray matter of the spinal cord eliminated the pain but not touch whereas a cut through other sections of the white matter of the spinal cord caused touch to be lost but not pain. INTENSIVE THEORY The prelude to intensive therapy was in Plato and E. Darwin in that pain not uniquely sensory (as per the specificity theory) but was an emotional state activated by light, pressure, or temperature. Wilhelm Erb, in 1874, also argued that pain can be generated by any sensory stimulus, provided it is intense enough, and his formulation of the hypothesis became known as the intensive theory The concept of nociception was developed in 1898 by the British physiologist, Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (1857-1952), who proposed the key concept of nociception: pain as the evolved response to a potentially harmful, "noxious" stimulus, but through competition and integration using the same neural pathways. The nociceptive part was readily grasped by scientists, but the integration and competition aspect required another half century to be accepted. The concept of pain as nociception represents a significant departure from the concept of the purpose of pain up to this point in time. Previously pain’s function was to heal, to punish, or to ennoble. Sherrington demonstrated pain was to serve as a warning sign. Treatment advances made during this time period included the isolation of morphine from opium. In 1806, after centuries of use of opium as a painkiller, Friederich Wilhelm Sertuerner (17841841), an apothecary's assistant in Westphalia, isolated the alkaloid of opium. He called it "morphium" after the Greek god of dreams, Morpheus. Later it was changed to morphia or morphine. In general, its use as painkiller would have to wait for the invention of the hypodermic syringe and hollow needle in the 1850s. It would remain the principal pain drug well into the twentieth century. For treatment of headaches (particularly those due to alcohol induced hangovers) the bromates were introduced in the 1860s. These drugs were frequently part of a mixture of nostrums or patent medications, and were also used to treat stress. Effectively this class of drug was the first minor tranquilizer (sedative-hypnotic). The primary drug used was sodium bromide which had a very long lasting effect, but also a very narrow therapeutic index. It caused severe gastritis, but in chronic use could be quite addicting with some consuming 5-6 bottles of the drug per day. The bromides were determined later to be carcinogens and were outlawed in 1975 with a few exceptions. The bitter tasting bromides were largely replaced with the introduction of the barbiturates in 1903, with the exception of Bromo-seltzer that remained popular for many decades. The xray was discovered in 1895, with almost immediate universal acceptance of xrays films for diagnostic purposes. SURGICAL ANESTHESIA The need for an adequate surgical anesthetic was wanting for many thousands of years with tapping on wooden bowls over the head until unconsciousness occurred, bilateral carotid artery compression to the point of unconsciousness, and holding children over natural gas until they became unconscious the preferred means of anesthesia. Later from the 9th to the 16th centuries, the soporific sponge was described in textbooks and other compilations as a means to attain surgical anesthesia but not without significant risk of death. The following is a recipe for the soporific sponge from Theodoric of Cervia from the work, Cyrurgia (Venice, 1498): "The composition of a savour for conducting surgery, according to Master Hugo, is as follows: take opium, and the juice of unripe mulberry (probably a textural mistake for black nightshade),hyoscyamus (henbane), the juice of hemlock, the juice of leaves of mandragora, juice of climbing ivy, of lettuce seed, and of the seed of the lapathum (dock) which has hard, round berries, and of the water hemlock, one ounce of each. Mix all these together in a brazen vessel, and then put into it a new sponge. Boil all together out under the sun during the dog days, until all is consumed and cooked down into the sponge. As often as there is need, you may put this sponge into hot water for an hour, and apply it to the nostrils until the subject for the operation falls asleep (he who must go under the knife,--llit. be cut into). Then the surgery may be performed and when it is completed, in order to wake him up, soak another sponge in vinegar and pass it frequently under his nostrils. For the same purpose, place the juice of fennel root in his nostrils; soon he will awaken." Chloroform was introduced in 1847 in England and was used extensively, whereas shortly thereafter diethyl ether was introduced in the United States. Because of the toxicity of chloroform ultimately diethyl ether replaced chloroform in the United States. Chloroform and diethyl ether were used in the late 1800s for production of general anesthesia for surgery and childbirth. Charles Gabriel Pravaz (1791-1853) of France, who invented the hypodermic syringe in 1851; and Alexander Wood (1817-84) of Scotland, who invented the hollow hypodermic needle in 1853. In 1869, Claude Bernard (1813-78), a French physiologist, injected morphine prior to the administration of chloroform or ether for general anesthesia. In 1884, the breakthrough came when Carl Koller (1857-1944), a Viennese ophthalmologist, discovered the anesthetic properties of cocaine. William S. Halsted (1852-1922), a Bellevue Hospital surgeon, blocked the inferior alveolar nerve with a four percent cocaine solution in November 1884 - the first mandibular nerve block. However, cocaine was found to be an addictive and dangerous drug. Coca cola was originally developed by Pemberton, a pharmacist, and was initially sold as a cure all for everything given that it contained relatively high concentrations of cocaine. Coca Cola contained relatively high amounts of cocaine, a very potent local anesthetic, from 1886 until 1891, when the amount of cocaine was lowered by 90%, then essentially eliminated after 1903. Heroin was originally synthesized in 1874 by Wright, and experiments on rabbits were not encouraging, therefore no further development of the drug occurred until Hoffman at Bayer Co. synthesized the drug in 1897. The creation of heroin was actually a chemist error since he was tasked with creating synthetic codeine to be used as a less addictive substitute for morphine. Instead heroin was nearly 3 times as potent as morphine yet was marketed by Bayer as a nonaddictive cough syrup from 1898 until 1910. It was also used to eradicate morphine addiction until it became apparent it was far more addictive than morphine given its passage across the blood brain barrier before deacetylation to morphine, thereby developing very high brain levels of morphine. The drug was universally removed from the world markets after 1925, but is still used in Britain in epidurals for labor pain and as a pain medication in the oral tablet form. Other 19th century advances in pain included the observations of Weir on causalgia pain produced by US Civil War wounds, the development of aspirin in 1898 as a substitute for the severely gastric irritating willow bark (contained salicylic acid) , and the application of hot mustard plasters used in 19th and early 20th century America as a treatment for pain based on the principle of counterirritation. Twentieth Century In 1916 Rene Leriche discovered causalgia pain in soldiers from the Great War could be partially alleviated through periarterial sympathectomy initially performed surgically. Later he blocked the sympathetic chain with procaine and found some of the patients had long lasting pain relief. This linked the sympathetic nervous system and causalgia. William K Livingston (1892-1966) studied the visceral neurological system and causalgia, noting similarities between the diffuseness of the pain and argued against absolute specificity. Livingston wrote in his Pain Mechanisms (1943): "I believe that the concept of 'specificity' in the narrow sense in which it is sometimes used. . . has led away from a true perspective. . . Pain is a sensory experience that is subjective and individual; it frequently exceeds its protective function and becomes destructive. The impulses which subserve it are not pain, but merely a part of its underlying and alterable physical mechanisms. . . The specificity of function of neuron units cannot be safely transposed into terms of sensory experience. "A chronic irritation of sensory nerves may initiate clinical states that are characterized by pain and a spreading disturbance of function in both somatic and visceral structures. If such disturbances are permitted to continue, profound and perhaps unalterable organic changes may result in the affected part. . . A vicious circle is thus created." By the 1950s, the specificity theory had been strongly supported by the work of Joseph Erlanger, Herbert Gasser, and Ainsley Iggo, who had recorded pain impulses from Livingston's Case Notes from single nerve fibers. But several investigators proposed a WWII Peripheral Nerve alternative physiological models to replace the specific Injury Patient, 1945 one-to-one pain pathway of perception and response, which might better explain the clinical observations ofBeecher, Leriche, Livingston, and others. These included the pattern theory of Graham Weddell and D.C. Sinclair, which suggested that pain perception was the interpretation of the spatial and temporal patterns of stimuli, and the multisynaptic modification system proposed by the Dutch surgeon Willem Noordenbos. However, these theories lacked strong experimental support. Henry Beecher further advanced the perception of pain by using experimental pain production and noted the differences between the experimental hospitalized and home groups. He concluded: "Thus emotion can block pain; that is common experience. It is difficult to understand how emotion can affect the basic pain apparatus than by affecting the reaction to the original sensation." Certainly psychological effects have great influence on subjective responses, not only pain but other responses as well. Every small boy has learned, knows, even though he does not consciously recognize the fact, that emotion can block the pain of a wound received during fighting but not perceived until the fight and the emotion have subsided." (From: Henry K. Beecher.Measurement of Subjective Responses: Quantitative Effects of Drugs. New York: Oxford University Press, 1959) In 1965, a collaboration between two self-described iconoclasts, Canadian psychologist Ronald Melzack and British physiologist Patrick Wall, produced the gate control theory. Their paper, "Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory," (Science: 150, 171-179, 1965) has been described as "the most influential ever written in the field of pain." Melzack and Wall suggested a gating mechanism within the spinal cord that closed in response to normal stimulation of the fast conducting "touch" nerve fibers; but opened when the slow conducting "pain" fibers transmitted a high volume and intensity of sensory signals. The gate could be closed again if these signals were countered by renewed stimulation of the large fibers. Ironically, the paper published came out of simply batting ideas back and forth and was subsequently proven with electrode stimulation of the forehead. The two had published a virtually identical paper 3 years earlier in a less well known journal, and it went completely unnoticed by the scientific and medical communities. The multidisciplinary pain clinic began when the young anesthesiologist John J. Bonica (1917-1994), was assigned to take charge of pain control at Madigan Army Hospital in Washington State in 1944, and found himself seeing "cases that baffled me." He sent the patients for consultations with colleagues: an orthopedist, a neurosurgeon, a psychiatrist, but "they knew less than I did." He proposed that the four meet twice a week at lunch for conversation and exchange of information on difficult pain problems. The success of this informal collaboration prompted him to establish a multidisciplinary pain clinic at Tacoma General Hospital in 1947, which he brought to the University of Washington in 1960. Bonica saw the idea of interdisciplinary collaboration as the key to the John Bonica understanding of pain. He described his clinic as "a totally different thing, much more fruitful and efficient. . . The basis of my program is patient care; the frosting is the research." (Quotations from the Oral History of John Bonica, 1993) In 1973, encouraged by the response to the gate control theory, John Bonica (shown here at another conference in 1972) organized a highly productive scientific meeting of some 300 pain researchers in Issaquah, (Seattle) Washington, where he won their unanimous endorsement of a new International Association for the Study of Pain based on the concept of interdisciplinary collaboration. Treatments of the 20th Century Brochure announcing the Issaquah conference, 1973 The synthesis of Novocain (procaine) by Alfred Einhorn (1856-1917) of Germany in 1905 finally provided a local anesthetic without the dangerous side effects of cocaine. It was introduced into the United States in 1907, and became the most popular anesthetic for dental procedures. Epidural blocks with cocaine were performed in the early 1900s with excellent pain relief results. Unfortunately the results are short acting and it wasn't until the administration of steroids epidurally in the 1950s and 1960s was it apparent that there were other receptors and structures that needed to be targeted for long-term relief. The facet was thought to be the source of much spinal pain (Ghormley ) until Mixter and Barr in 1934 demonstrated clinical confirmation that disc herniations previously described in the extensive pathology spine sections dissected by Schmorl, are a source of pathology. Almost immediately attention turned to the disc as a source of pain, and surgical discectomy was born. Later, Nik Bogduk defined the anatomy of the medial branch of the posterior primary ramus innervating the facet joints. Much later the sacroiliac joint anatomy was defined with dissections by Frank Willard and Way Yin. Procedures were developed to treat pain associated with each anatomical structure. Spinal cord stimulation was invented in 1967 first performed by Shealy and subsequently intrathecal infusion pumps were developed. During the 20th century there continue to be advances in not only the theories of pain. The most significant advance in the series included gate control theory (Melzack/Wall 1965) which explains why there are many influences on perception of pain and also why there does not seem to be a direct relationship with pain intensity and stimulus intensity. This becomes very important chronic pain which is no longer seen as merely an extension of acute pain. In the 20th century there were many advances made in analgesics, the use of anticonvulsants to slow pain pathways, anti-inflammatory agents, and the synthesis of many new opioids. Pain clinics were developed in the 1980s as a means of handling chronic pain, frequently in a multidisciplinary approach. The use of psychological counseling, physical and functional rehabilitation, medication management, peripheral nerve blocks, central nerve blocks, neural destructive techniques, and neuromodulation techniques were all packaged in a single clinic setting. Because of the expense of maintaining such a cadre of individuals providing such care, the full multidisciplinary clinic is not nearly as popular as it once was. Currently it is more popular to utilize an interdisciplinary clinic in which selected disciplines are brought in to meet the patient’s specific needs or the patient is sent to other specialist clinics working in concert to help control pain. The advances in neurophysiology over the past several years are profound and will be discussed elsewhere Appendix A Methods of Torture to Produce Pain If you have a weak heart, it is suggested you skip this section due to the graphic nature of the content. The Crusades were winding down around 1250-1300 AD and methods of securing confessions from the heathen became commonplace. Eventually, methods of torture became so common, they were used to quell civil disobedience, inflict pain due to crimes, and to settle arguments in addition to their continued original use. Much of Europe adopted the methods of torture used as punishment to inflict pain. Wooden wedges were forced underneath the toenails to invoke confession from the criminal or the heretic. The toenails often became infected and other tortures were applied if this was not enough for confession. A scissor like tool was used to slice the tongue up after the victims mouth was forcibly opened. The copper boot was inserted onto the foot of the criminal and filled with molten lead causing significant burns. The sprinkler was a device filled with molten metal and dripped on the stomach, back, and other body parts of the victim. During the water torture, the victims nostrils were pinched shut and fluid was poured down his throat. Instead of water, sometimes vinegar, urine, or urine and a combination of diarrhea were forced down the throat. The thumbscrew was a sharp tipped device that was tightened on the thumb until it was crushed. The tool was also used on toes. Toothed bars were used to squeeze the victim's testicles til they were destroyed. Another method of torture was the application of heavy weights to the legs of a person sitting on a Spanish donkey until the force was so great that it destroyed the perineal area, penis, and testicles. The Foot Press slowly squeezed the naked foot between the iron plates lined with sharp spikes to crush the bones of the foot. The Scottish Boot was placed around the ankle of the victim and then wedges were forced into the ankle. The name breast ripper was a device with 4 sharp prongs that were impaled into the breast and back, and while the person was held down, the device was forcibly moved upwards thereby removing the breasts and muscle. The pear, shown at the right, was a metal object that is shoved inside the mouth anal cavity and vagina. Once in place the screw at the end was turned and the pear opened up inside the cavity. This caused much damage and lead to death. The victim was bound on an oblong wooden frame with a roller at each end. If the victim refused to answer questions, the rollers were turned until the victim's joints were pulled out of their sockets. The branks were a mask that had a metal piece that goes in your mouth. The mouth piece has spikes on it, which unables you to talk. The Juda Cradle is a horrible torture. The victim is hung above a cone pyramid type object and then is lowered upon it. the sharp tip of the cone or pyramid is forced into the area between the legs. The headcrusher simply crushed your head. The whirligig was not that bad of a torture. It just span the victim til they puked. The cat's paw was a short pole with a pitch fork at one end. It was used to tear the the flesh of the victim. The heretic fork, shown to the left, was a two sided prong that went between your chin and your chest. You could not talk with instrument in place and it was very painful. The chair of spikes was a chair of spikes. The victim would sit in the chair and weights would be applied onto the victim forcing his body into the metal spikes. And of course we are all familiar with drawing and quartering in which ropes were attached to the legs and arms, each one hooked to one of four houses made to run in opposite directions. Hanging was used as a death penalty but with the person only partially hung, they were subsequently disemboweled.