Normative and Allocation Role Strain

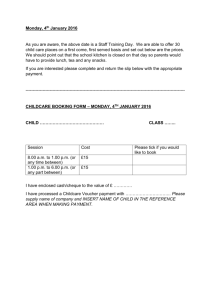

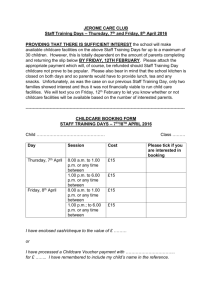

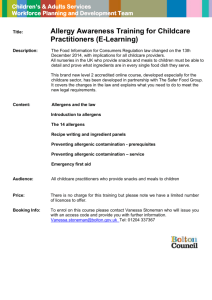

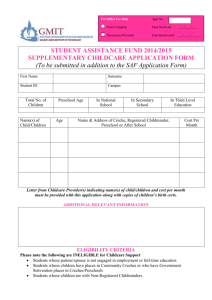

advertisement