on factions

advertisement

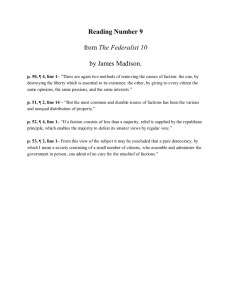

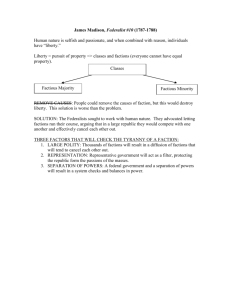

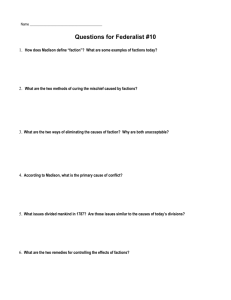

Lea Ypi London School of Economics and Political Science / Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin 1st DRAFT - Please do not cite without permission, comments welcome l.l.ypi@lse.ac.uk "It is true that some divisions are harmful to republics and some are helpful": on factions, parties, and the history of a controversial distinction Partisanship, it is often said, involves efforts to harness political power not for the benefit of one social group among several but for that of the polity as a whole, as this benefit is identified through a particular (but not partial) interpretation of the public good. In this sense partisan practices differ from the activity of factions, although for a very long time the two were assimilated to each other. In this paper I examine the reasons for that assimilation by looking at two different critiques: a holist and a particularist one and suggest that the distinction between parties and factions could be seen as one way to respond to these critiques. If parties are perceived and defended as distinct from factions and as essential to the political community, their contribution to the political process need not be seen in tension with either justice or order but as conducive to both. But while the distinction between factions and parties is normatively promising, that promise can only be maintained if, as critics of partisanship point out, certain constraints are in place. What kind of constraints these are and to what extent they are reflected in the activity of parties as they are (rather than as they should be) is the topic of the last part of the paper. 1. Introduction "Le terme parti par lui même n’a rien d’odieux, celui de faction l’est toujours”.1 With those few words, the entry on "faction" that Voltaire contributed to the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert crystallised a distinction, that between party and faction, that all successive attempts to defend the modern idea of partisanship have since unfailingly endorsed.2 Such an endorsement is not surprising. Although the analysis of partisanship as a practice necessary to the exercise of popular sovereignty is essentially a modern phenomenon, the critique of parties as equivalent to factions and corrupting the public spirit has been with us for much longer. 1 "The term party has nothing despicable in it, that of faction always is". Voltaire, François-Marie Arouet, "Faction" in Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 6, Paris, 1756, p. 360. 2 Giovanni Sartori, who also endorses Voltaire's distinction at the beginning of his excellent analysis on party systems, rightly points out that Voltaire himself seemed unaware of the evaluative implications of his definition Giovanni Sartori, Parties and Party Systems : A Framework for Analysis (Colchester: ECPR, 2005). p. 4. Indeed, when it came to defining parties, Voltaire was less consistent: "a head of a party is always a head of faction", he argued, and the main meaning of factions is "a seditious party in government". 1 Defenders of partisanship have always been aware of the weight of the critique and conscious of the need to address it. In what is now considered a pioneering argument in favour of the modern party system, Edmund Burke suggested that it was easy to distinguish between the "generous contention for power" based on "honourable maxims" characteristic of principled partisans and "the mean and interested struggle for place and emoulment" displayed in practices "below the level of vulgard rectitude".3 Almost exactly one hundred years later, another classic defence of parties, that offered by the Swiss jurist Johan Kaspar Bluntschli, tackled the distinction in no ambiguous terms. "We need to distinguish party from faction", he argued. "A faction is a distorted party; a denatured party". Parties are "necessary and useful at the higher levels of conscious and free public life", factions are "unnecessary and corrupting".4 Yet another one hundred years later, an important book which only contained a few sparse remarks on political parties but continues to shape debates on the relation between justice and political institutions echoes these thoughts. A well-ordered constitutional regime, Rawls argues in A Theory of Justice, is characterised by the fact that political parties are not "mere interest groups petitioning the government on their own behalf". They must instead "advance some conception of the public good".5 While defenders of partisanship hold on to the distinction between factions and parties, detractors tend to highlight its fragility. For the former, parties contribute to the development of the public spirit and factions undermine it. For the latter, factions and parties both represent partial associations which, in so far as they advance particular commitments are seen as incompatible with the development of a general will. Both lines of argument have a venerable history. For defenders of partisanship, parties are "oriented toward an ideal aim" which promises to "benefit everyone"; factions "strive to achieve an improper, selfish, goal".6 For their critics, "every party is criminal" and "every faction is thus criminal".7 Some celebrate how "parties complete the state" and lament that "factions rip it apart".8 Others warn, "in the most solemn manner against the baneful effect of the spirit of party " and the "alternate domination of one faction over another".9 For those who abhor partisanship, the difference from factions is only in degree. For those who appreciate its virtues, it is a difference in kind. But what explains that difference? And what accounts for the apparent similarity? 3 Edmund Burke, Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents, (1770/1999), Liberty Fund, p. 92. Johann Caspar Bluntschli, Charakter Und Geist Der Politischen Parteien (Nordlingen, 1869). 5 John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Rev. ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999)., p. 195. [This distinction is fundamental to virtually all contemporary defences of partisanship, see the recent discussions in Muirhead, Rosenblum, but also some older references from Hume to Bolingbroke and from Hegel to Kelsen.] 6 Mohl, Die Parteien in der Staate, in Enzyklopaedie der Staatswissenschaften, pp. 648-52. 7 St Just cited in Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, p. 10. 8 Bluntschli, Charakter Und Geist Der Politischen Parteien. pp. 1-12. 9 George Washington, "Farewell Address to Congress," in American Presidents: Farewell Messages to the Nation, 1796-2001, ed. Gleaves Whitney (Oxford: Lexington Books, [1796]). p. 21. 4 2 In this paper I introduce the origin of the terms "faction" and "party", examine their development and consider two different critiques of partisanship: a holist and a pluralist one. While both critiques highlight the tendency of partisanship to fragment the public good, they do so for different reasons: a concern with justice in the first case, and a concern with order (or stability) in the second. I then suggest that the distinction between parties and factions which accompanies the consolidation of the modern state could be seen as one way to respond to these critiques. If parties are explicitly defended as distinct from factions and as essential to the maintenance of the political community, their contribution to the political process need not be seen in tension with either justice or order but as conducive to both. However, while the distinction between factions and parties is normatively promising, that promise, I suggest, can only be maintained if certain constraints, on which critics of partisanship draw attention, are in place. What kind of constraints these are and to what extent they are reflected by parties as they are (rather than as they should be) is an issue that I only begin to sketch in the last part of the paper. 2. The spectre of faction The term "party" which began to circulate in the early Middle Ages in French, Italian and German comes from the Latin "pars" and the verb "partire" which means "to divide" or "to set apart". Before its use in the XVIII century to denote the key political agents of the modern representative system, it was deployed in political contexts to refer to associations or groups of people consolidated around different leaders and following aims that were distinct and often in conflict with each other (e.g. the party of Ceasar or Pompey or the party of the Guelphs against the Ghibellins).10 The term "faction", on the other hand, derives from the Latin verb "facere", which means "to do" or to "act", and "factio" can be translated as "way of acting".11 As Voltaire's entry for the Encyclopèdie clarifies, the term circulated with reference both to a certain posture or way of being active i.e. denoting the place occupied by a soldier in his post (en faction) but also the seditious activity of a politically motivated group within a community.12 Both terms are often translated as synonymous with the Greek term στάσις (stasis) whose use is wider but which in its root-sense means "placing", "setting", "standing" and thus, 10 For an excellent conceptual history of both terms see Klaus Von Beyme, "Partei, Faktion," in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon Zur Politisch-Sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, ed. Otto Bruner, Werner Conze, and Reinhart Koselleck (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1978). 11 See the useful discussion in Robin Seager, "Factio: Some Observations," The Journal of Roman Studies 62 (1972). 12 Voltaire, "Faction", cit. above. See also the discussion in Sartori, Parties and Party Systems, p. 4-5. 3 similarly to faction, both occupying a specific position and acting in a certain way.13 Like the term faction, stasis was deployed from very early on (roughly 600BC) in specifically political contexts to refer to adopting a political position, as well as to disagreement, dispute, internal conflict, struggle for power, revolution, civil strife and even civil war.14 It is interesting to see how for the Greeks a term which initially had originally neutral connotations of staticity, settlement, and permanent occupation of a place or station, lost such neutrality when applied to political contexts.15 Taking sides, maintaing a position, adopting a stance, all attitudes that we tend to link to the spirit of partisanship, seemed to be immediately associated with a threat of division, the disruption of political community, a conflict for power and the worse excesses of sedition, civil war and revolution. Nowhere is this critique captured better than in Thucydides chilling rendition of the conflict between pro-Athenian and pro-Spartan groups that tore apart the small island of Corcyra at the beginning of the Peloponesian war. Opposing partisans all claiming to act in the name of the common good engaged here in a destructive struggle for power which, as Thucydides says, resulted in the most appalling atrocities and the most severe punishments "beyond anything required by justice or civic interest". The public whose interests the parties professed to serve, Thucydides emphasised, was in fact "their ultimate prize" and citizens who had remained neutral were destroyed either "for failing to join the cause or out of resentment at their survival".16 Factionalism undermined familial trust, destroyed the civic bond and showed human nature for what it really was: a "slave of passions" and "a stronger force than justice".17 Peace and civic order could in the end be restored only after "nothing worth reckoning was left of the other party".18 While occasionally more cautious in distinguishing the term "part" (pars/partes) from "faction" (factio), Roman historiography also abounds with warnings of the potential for civic discord fuelled by partisan disputes. Here, the terms "part" and "party" are mostly invoked in a descriptive fashion, to denote different parts in court or, in political contexts, different groups of people gathered around different leaders, with distinctive goals and aims. Thus when Cicero writes in De Republica that the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus had "divided one people into two 13 Von Beyme, "Partei, Faktion." p. 678. For a definition of stasis see Werner Riess, "Stasis," in The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, ed. Roger S. Bagnall, et al. (Oxford: Wiley, 2013). 14 See Andrew Lintott, "Violence, Civil Strife and Revolution in the Classical City 750-330 Bc," (Oxford: Routledge, 2014). p. 34. 15 See for a discussion of this issue M. I. Finley, "Athenian Demagogues," Past & Present 21, no. 1 (1962)., pp. 6-7 and Moshe Berent, "Stasis, or the Greek Invention of Politics," History of Political Thought 19, no. 3 (1998). 16 Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, trans. Martin Hammond (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)., Book III, 82 ff. 17 Ibid, Book IV, 84. 18 Ibid, Book IV, 48. 4 parts" (duas partes)19 or when Sallust explains the difference between patricians and plebeans as a difference between two parts (duas partes) of the political community20 the term has a neutral meaning.21 Faction, on the other hand, almost always circulated as a pejorative. Although this had also not always been the case, the transition from the neutral to the derogatory use of the term is easier to explain. Factio was deployed in Roman comedies (e.g. in Plautus) to indicate a certain "way of doing things", "capacity to get things done" or, even more accurately, "influence" displayed by agents who were more powerful than others by virtue of their birth rank, wealth or social status.22 Thus when the term was made popular by Sallust in his Jugurthine War to indicate the contrast between an aristocratic faction that concentrated wealth and influence and the power of a dispersed mass of people, it was not surprising that he referred to partisanship and factionalism as "vicious practices". Factionalism destroyed the initial balance of "mutual consideration and restraint" that had characterised the previous years of the republic during which, he stressed, "among the citizens, there was no struggle for glory and domination". 23 The emergence of factions brought with it "greed without moderation" and "devastated everything, considered nothing valuable or sacred, until it brought about its own collapse". Indeed, Sallust emphasised, as soon as there were people who "put true glory above unjust power, the state began to tremble and civil strife began to rise up like an earthquake".24 It is interesting to note that the term "factio" was not used by Sallust to denote a particular political agent but the more abstract tendency to concentrate individual influence in a narrow group with self-serving aims.25 Indeed, in an earlier passage of the Jugurthine War, commonality of purpose is considered to be friendship in the case of good men, and faction in 19 Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the Commonwealth and on the Laws, trans. James E. G. Zetzel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [54BC] 1999). 1, 31. 20 Sallust, "Letters to Caesar" in Fragments of the Histories. Letters to Ceasar (Cambridge MA: Loeb Classical Library, 2015) 2, 5, 1 [double check Eng. translation]. 21 It is also worth emphasising that the Romans meant by "parties" something very different from what we have in mind when we think of them as collective agents with a representative function, indeed some authors have even objected to the use of the term in the Roman context. For a defence of the terminology which also highlights the limitations, see Lily Ross Taylor, Party Politics in the Age of Caesar (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1949). and for a critique see Seager, "Factio: Some Observations." as well as Andrew Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999). pp. 173-76 22 See Seager, "Factio: Some Observations." p. 53, Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic. pp. 165-66 23 See Sallust, "Jugurthine War" in Sallust, Catiline's Conspiracy ; the Jugurthine War ; Histories, trans. William Wendell Batstone (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010). 41, 1-6. 24 Ibid, 41, 9-10. 25 Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic. p. 165 and Taylor, Party Politics in the Age of Caesar. p. 9. 5 the case of others.26 Following the same path, in a revealing section of De Republica, Cicero gave the term an even more specific and enduring political connotation. Here the term faction (factio) was used to refer to a group that is formed "when certain individuals because of their wealth or family or other resources control the commonwealth" although they call themselves ‘‘the best people" (optimates)".27 The link between factionalism and a degenerate form of aristocratic rule remained relatively persistent and continued to be associated to the destruction of the political community. We find it, for example in Augustine's City of God, when he argues, paraphrasing Cicero, that a faction is nothing more than the unjust form in which rule by the best tends to degenerate ("injusti optimates quorum consensum dixit esse factionem"). Again here, when such unjust rule takes hold of the city, Augustine emphasises, the commonwealth is not merely flawed but "ceases altogether to be".28 We already find in these early definitions the most important themes around which subsequent critiques of partisan activity tend to concentrate: the purely destructive tendencies contained in factional divides, the detrimental effects of partisan selfishness, the potential for domination contained in the unilateral exercise of power, and so on. What is even more interesting is the idea that equates factions to depraved political groups, groups that are supposed to embody the best people in charge of ruling the city but have instead concentrated wealth and power and use it only to advance their own purposes. To put it differently, factional activity appears here as just another name for the kind of oligarchical rule that emerges in book VIII of Plato's Republic and in book V of Aristotle's Politics following the decay of aristocratic regimes. Factions represent a corrupt display of partisan passions, triggered by arrogance, envy and the desire to accumulate wealth, and leading to the explosion of a destructive conflicts between opposing parts of society. The difference between partisanship and factionalism is only one of degree rather than kind. Indeed the gradual escalation of one into the other is well captured in a famous passage from Machiavelli's Discourses sketching the phenomenology of civil strife: conflicts between individuals generate offense, "which offense generates fear; fear seeks for defence; for defense they procure partisans; from partisans arise the parties in cities; from parties their ruin"29. Despite the emerging meaning of the term "party" during the XVIII century to refer to more abstract political agents with a claim to embody popular sovereignty (a point to which I shall return), anxiety over the undue effects of their influence over the rest of the political 26 See Sallust, Jugurthine War in Sallust, Catiline's Conspiracy ; the Jugurthine War ; Histories., 31, 14-5. Note however that in this edition factio is translated as cabal. 27 Cicero, On the Commonwealth and on the Laws. 3, 23. 28 Augustine, The City of God against the Pagans (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [426BC] 1998)., Bk, 2, ch. 21, p. 78. 29 Niccolò Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, trans. Harvey Mansfield and Nathan Tarcov (Chicago: Chicago University Press, [1517] 1996)., Bk I, ch. 7, 1. 6 community has been one of the most enduring aspects of the critique of partisanship. The tendency to equate partisanship with oligarchy is echoed in Alexander Pope's definition of party spirit as "the madness of the many for the gain of the few"30 or in Moisej Ostrogorskij's admonition that as soon as a party is formed, "even if created for the noblest object, it tends to degeneration"31, or in Robert Michels' stark reminder that the tendency to oligarchy is "inherent in all party organizations".32 As we saw in the previous pages, those who sought to resist the critique did so by defending the irreducibility of partisanship to partial interest: "If a party is not a part capable of governing for the sake of the whole, that is, in view of a general interest, then it does not differ from a faction. Although a party only represents a part, this part must take a non-partial approach to the whole".33 But do such defences of partisanship succeed? What exactly does it mean for a part to take a non-partial approach to the whole? Under what conditions is it possible for it to do so? Are these conditions themselves subject to partisan dispute? That parties should exhibit a non-partial commitment to the whole might sound like an oxymoron. Detractors of partisanship have long pointed out the apparent (or not so apparent) inconsistency. Their arguments stem from two longstanding critiques in the history of political thought: a holistic one which casts parts against the whole, and a pluralistic one which acknowledges their persistence but rejects partisanship as a vehicle for channelling disagreement.34 On the first line of argument, parties represent a threat to justice; on the second they represent a threat to order. Both, as we shall see, draw attention to an important aspect of the relation between partisanship and factionalism, and both can only be overcome after careful rethinking of what a party is, and of the conditions under which its commitment to a non-partial account of the public good can be promoted. Let me try to elaborate more on each. 3. Justice and the holistic critique of faction The holistic critique of faction is a familiar one. Nowhere is it captured better than in Rousseau's famous discussion of partial associations as an obstacle to the development of the general will, a discussion that takes shape in the context of a famous section of The Social 30 Alexander Pope, Thoughts on Various Subjects, REF. Moisey Ostrogorsky, Democracy and the Organisation of Political Parties, (New York 1922), vol. 2, p. 444. 32 Robert Michels, Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (New York: The Free Press 1962), p. 50. 33 Sartori, Parties and Party Systems : A Framework for Analysis., p. 24. 34 For further analysis of the distinction see Nancy L. Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels : An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008)., chs. 1 and 2. 31 7 Contract entitled "Whether the General Will can err". Here, as is well-known, Rousseau develops the much discussed distinction between the general will and the will of all: the former organic and committed to the good of the whole, the latter aggregative, only focused on private interests and merely replicating a sum of these. It is here that Rousseau emphasises how partial associations exacerbate the will of all and undermine the general will. When these partial associations arise, he argues, small associations emerge "at the expense of the large association" and "the will of each one of these associatons becomes general in relation to its members and particular in relation to the State".35 And, when one of these grows so much that it ends up prevailing over the others "there is no longer a general will, and the opinion that prevails is nothing but a private opinion".36 If partial associations undermine the general will, the latter can only be expressed if the former are abolished. Therefore, as Rousseau famously notes, it is crucial that "in order to have the general will expressed well, there be no partial society in the State, and every Citizen state only his own opinion".37 Rousseau's analysis represents the culmination of a longstanding tradition of similar complaints about difficulties with promoting the good of the whole (which requires commitment to reason) and the disruption caused by partial associations (which is in turn influenced by passions).38 The spirit of his remarks is similar to those of Spinoza's reflections in Ethics where he emphasises, in the context of a similar distinction between reason and passion, that "[W]hatsoever conduces to man's social life, or causes men to live together in harmony, is useful, whereas whatsoever brings discord into a State is bad".39 Before that, Hobbes had also warned of the incompatibility of all partisan associations with the exercise of sovereign power: "all uniting of strength by private men, is, if for evill intent, unjust; if for intent unknown, dangerous to the Publique, and unjustly concealed". Factions, for Hobbes are "unjust" because they undermine "the peace and safety of the people" and take "the Sword out of the hand of the Soveraign".40 And even Locke, who thought that there was occasionally nothing wrong with taking the sword out of the hands of the sovereign, especially if the latter is an unjust tyrant, was careful to point out that the right to resist belonged to the people as a whole and could hardly be exercised "as often as it shall please a busy head, or turbulent spirit, to desire the 35 Jean Jacques Rousseau, "Of the Social Contract," in The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings, ed. Victor Gourevitch (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [1762] 1997)., ch. 3, 2-3. 36 Ibid. 37 Ibid. 38 For an excellent overview on the idea of party in the XVIII and XVIII century see Cotta, Cattaneo, Compagna, Palano, ch.4. 39 Benedict de Spinoza, Ethics (London: Penguin, [1677],1996), part IV, prop. 40, p. [add Bacon] 40 Thomas Hobbes, The Leviathan, R. Tuck ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991)., ch. XXII, 121-2. 8 alteration of the government".41 Indeed, in granting that "the pride, ambition, and turbulency of private men have sometimes caused great disorders in commonwealths", Locke pointed out that "factions have been fatal to states and kingdoms" and that such divisive attempts only contributed to partisans "own just ruin and perdition".42 It is tempting to dismiss the holistic critique of parties as an implausible (and by now outdated) instance of dogmatic commitment to a unitary view of the political world that is averse to conflict and rejects pluralism and change as undesirable features of human interaction.43 Longing for perfection and oriented by a utopian belief in the possibility of realising a perfect society once and for all, holism, so the argument goes, treats all parties as dangerous and obnoxious, issues constant warnings about the factional disruption of civic unity, and promises peace that can be delivered only by a divine legislator or mythical founder. Indeed, critics of holism emphasise, in so far as pluralism about conceptions of the good is taken for granted, conflict and change constitute unavoidable features of human life and holism seems to simply ignore them.44 Holism is anti-political, and its antipolitical stance stems from the belief in the possibility of identifying the public good without granting that partisan rivalry might make an important contribution to the process through which that good is progressively articulated.45 Hence all parties are thought of as factions and all factional conflict is rejected as divisive. But I think that the temptation to dismiss the holistic critique of parties and factions as anti-political must be resisted. The fact that holists often struggle to distinguish between factions and a more honourable form of political division, and the arguments they provide in 41 John Locke, Two Treatises on Government, ed. Peter Laslett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [1690] 1988)., ch. XIX, section 229. 42 Ibid. The disruption such factions caused, Locke warned, could only have had a chance of succeeding in bringing about a political change if the mischeif they caused would "be grown general, and the ill designs of the rulers become visible, or their attempts sensible to the greater part, the people". Locke's observations in the passage just cited might be read as an early attempt to distinguish between a kind of partisanship detrimental to the public good and which only serves the narrow interests of particular 'turbulent heads', and a kind of oppositional activity that claims to relate to more generalisable concerns of the whole people. In fact, I think his observations are much more continuous with a holist argument which condemned partisanship precisely in the context of acknowledging the right to resistance of a whole people. Thomas Aquinas had made a similar case in much the same context. Although he granted that it was not only a right but also a duty of citizens to remove an unjust tyrant, one also had to be careful about the potential for deterioration into an even worse form of tyranny. For, as Aquinas put it, "should one be able to prevail against the tyrant, from this fact itself very grave dissensions among the people frequently ensue: the multitude may be broken up into factions either during their revolt against the tyrant, or in process of the organization of the government, after the tyrant has been overthrown". See Aquinas, De Regno, ch. VII, 44. 43 For a similar critique of holism in the context of a defence of parties see Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels : An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship. pp. 28 ff. One finds similar complaints characterising also so-called realist critiques of political moralism. 44 See on this issue in addition to Rosenblum cit., also Sartori, cit. 45 For a similar critique of holism in the context of a defence of partisanship, see Ibid., p. 28. For similar critiques of political moralism see also authors in the agonistic and realist tradition, e.g. Mouffe, Honnig, Stears, Newey, Gray, Sleat, Rossi etc. 9 motivating that difficulty are revealing. But what they reveal is not so much the holist hostility to partisanship as symptom of its limitations in grappling with the political, as much as the limitations of a certain conception of the political in guaranteeing an appropriate relation between conflicting parts. Indeed, I want to go even further and suggest that when defenders of partisanship distinguish parties from factions, it is because they themselves are implicitly acknowledging the force of an important part of the holist critique. That implicit recognition however, needs to be brought out more clearly, and where necessary defended. Let me explain. Although ultimately motivated by the concern with stasis and the disruptive threat that factional strife poses to the political community, holist scepticism toward the value to partisanship has less to do with fear of political conflict as such and more with an attempt to reflect critically on how political conflict ought to be channelled so that no group ends up suffering from injustice. Therefore, rather than eliminate conflict altogether, holists seek to regulate it in such a way that different parts can interact with each other in the right way; indeed that harmony between the parts is precisely what Plato (and many others since) thought was the essence of justice. Harmony here does not mean that the sources of conflict are abolished: if they were, one would not need justice at all. But if justice is needed to allow all parts of the polity to pursue their ends (or discharge their function, as Plato would have said) without one prevailing over the others, justice itself cannot be conceived as the mere outcome of partisan conflict. If what is required to regulate conflict were itself the outcome of that conflict, justice would simply reflect the interest of whoever prevails in the conflict. Or to, put it differently, justice would simply end up being defined as the interests of the stronger party. That justice should not be defined as that which merely reflects the interests of the stronger party is of course Thrasymacus's definition of justice that Socrates sets out to defeat in the course of Plato's Republic. Only by appreciating what is at stake in the contrast between two different understandings of justice: justice as harmony between parts and justice as that which emerges from political conflict do we actually see what is at stake in the holist hostility to partisanship and its refusal to distinguisg between parties and factions. Unconstrained partisanship runs the risk of turning justice into a mere instrument of power politics and power politics helps no one, not even those who might initially benefit from it.46 But notice that in articulating this view, holists do not ignore political conflict or express an anti-political stance, as many critics would have it.47 On the contrary, it is because conflict is taken so seriously that the problem of justice as that which is required to prevent conflict from becoming a source of ongoing domination of one part by another becomes such a pressing one. 46 Indeed, this is the surprising claim Plato makes in The Republic when he argues that justice is more advantageous than injustice. 47 See on this issue Rosenblum, On the side of angels, cit. but also many realist critiques of political moralism that take a similar form. 10 As we saw in the previous pages, the term "faction" circulated in the ancient world always in connection to the abuse of power by a particular group of citizens who is supposed to rule in the name of the whole people and instead uses its strength and position of advantage to advance its own self-interest. Plato's account of the degeneration of what is supposed to be rule by the best (aristocracy) in rule by the few (oligarchy) in book VIII of The Republic is here the paradigmatic example of a factional accumulation of power to which many other authors, from Cicero to Augustine, and from Hobbes to Rousseau, continue to refer. In a political community where different groups have distinctive and often conflicting interests, the accumulation of offices and wealth, the growth of private property which exacerbates comparisons between citizens, and the envy and mutual hostility that results from such comparisons, risk driving animosities between groups in a destructive direction. Those with more money and titles end up occupying advantageous offices and positions and make laws that exclude the many who are only seen as means to promote their own self-interests. Public decisions are then corrupted by those special interests that enter the political sphere, and the general will no longer tracks what is right. As Rousseau puts it in a passage of the Discourse on Political Economy, public deliberation and the general will always coincide, except "if the people is seduced by private interests that some few skillful men succeed by their reputation and eloquence to substitute for the people's own interest".48 If justice is reduced to whatever results from adversarial encounters, justice ends up serving the interest of the stronger party. And if justice serves the interest of the stronger party, it can only exacerbate conflict rather than help to regulate it. The holistic critique is therefore not the result of a simplistic failure to appreciate the positive value of partisanship in political circumstances where pluralism characterises political life. On the contrary, holism's concern with justice seems plausible if we keep in mind the destructive form that partisan conflict can take if a plurality of interests confronts each other in the political sphere without a method for distinguishing between more or less reasonable instances of disagreement. Justice, in other words, is necessary for an impartial adjudication of the relation between different interests; it is necessary to contain the destructive form that conflict between parts of society can take if interests enter the political sphere entirely unmediated by principles. Without reflecting on how the interests of particular groups fit with a collective attempt to express and regulate the relation between such interests through principles of justice, the political sphere ends up becoming a realm of domination of the weaker party by the stronger party, and partisan disputes are difficult to distinguish from factional strife. 48 Jean Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on Political Economy" in The Social Contract and Other Later Political Writings, cit. p. 8. 11 It might be helpful to bring this section to a close by revisiting Rousseau's famous holistic critique of partial associations with which I started to see if we can now reinterpret it. Although Rousseau's account is often dismissed as a form of quasi-totalitarian mocking of essential and unavoidable pluralism, his thoughts are in fact much more nuanced. In the very section of The Social Contract where his apparent hostility to parties is expressed, the antipartisan argument is qualified in a little-noticed footnote that refers to Machiavelli's distinction between different kinds of divisions in the political community.49 The truth is, Machiavelli had argued in the Florentine Histories, that "some divisions harm Republics, and some benefit them; harmful are those that are accompanied by factions and parties; beneficial are those that do not give rise to factions and parties".50 But since the legislator knows that conflicts and enmities are unavoidable, he must make "the best provision possible against factions". 51 In citing these same passages, Rousseau comments further on Machiavelli's suggestion by recommending that "if there are partial societies, their number must be multiplied and inequality among them prevented, as was done by Solon, Numa and Servius".52 The real problem for Rousseau, as one can see here, is not with partisanship per se but with the conditions under which a just interaction of partisans is possible. And interestingly, the answer to the problem consists not in establishing laws that suppress these differences, but in correcting inequalities between parts, such that no partisan group can prevail over the others.53 Indeed, the examples of successful legislators that Rousseau mentions (Solon, Numa etc.) are far from indicating his approval of reforms that sought to abolish partisanship; quite the opposite. Solon's famous antipartisanship law condemned to loss of citizenship all those citizens who, in times of civil strife, refused to join one of the struggling parties: it was a law that intended to pluralise political opposition, not to eliminate it by asking people to bracket from their political disagreements. One of Numa's most admired initiatives, as Plutarch reports, was to divide the city in smaller parts, allow different associations of citizens distinguished by trade to flourish and to multiply but then make sure that none of them had more power than the others.54 The way to correct the general will from making mistakes, once conflict is acknowledged as unavoidable, is to correct inequalities between parts and to ensure that a plurality of associations can flourish under conditions that prevent some from becoming a source of domination for others. For that however one needs principles of justice. And yet those 49 Rousseau, "Of the Social Contract.", ch. 3, 4, p. 60. Machiavelli, Florentine Histories, Bk. VII, ch. 1. 51Rousseau, "Of the Social Contract.", ch. 3, 4, p. 60. 52 Ibid. 53 "That if there are partial societies, their number must be multiplied and inequality among them prevented, as was done by Solon, Numa and Servius. 54 On Solon's law see Plutarch, "The Life of Solon" in The Parallel Lives, vol. 1, Loeb, p. 20 and on Numa see ibid. "The Life of Numa", 17. For further discussion of the Solonian law see Joseph A. Almeida, Justice as an Aspect of the Polis Idea in Solon's Political Poems, (Leiden: Brill 2003), pp. 13-15. 50 12 principles of justice cannot themselves be subject to unconstrained partisan dispute, they need to be formulated by parties that are motivated by general, rather than particular interests, and in doing so they need to abstract from particular interests and goals. Notice how here, the holist attraction for the universal is not the cause of partisan anthipathy but an effect of the reflection on the detrimental consequences of partisan conflict whenever we take people as they are. Where asymmetries of position, wealth, and opportunities define particular partisan groups and are left unconstrained, they end up becoming a source of inequality and potential domination, threatening the integrity of the general will. Justice is required to harmonise conflict rather than to suppress it, and some kind of general, supra-partisan agreement on the fundamental principles through which this can be achieved (again, in Rousseau's terms: a general will) is essential to ensure that partisanship is beneficial rather than harmful to the political community. Although neither Rousseau nor (as we shall see in the next section) Machiavelli before him went as far as making a distinction between factions and parties to explain how the latter might contribute to the formation of such general will, their remarks on the relevance of the distinction between private and public interests give us some indication of what one needs to be begin with. To sum up, a framework of justice (i.e. the one that is required to avoid inevitable conflicts among human beings become purely destructive) is recognised by holists as beyond partisanship and in some ways necessary to regulate partisanship. If political institutions are arranged so as to reflect these norms, and if citizens abstract from self-referential needs and aims in articulating their concerns and commitments, a fair mechanism for regulating conflict becomes available. This is not to exclude that disagreements on principle will persist even once such efforts at advancing such interpretations of the public good are in place. Indeed, this is exactly what is at stake in the apparently paradoxical idea that parties should seek to articulate a non-partial view of the public good. That idea acknowledges that pluralism and disagreements might be unavoidable but does not thereby entail that all disagreements should be relativised and applauded without constraints. If such disagreements can be channelled by appealing to reasons that can be generally shared, if partisanship becomes a vehicle for generating public justifications rather than a mechanism of representation of groups' interests, disagreements become productive rather than destructive, they contribute to identify what is in the public good rather than undermine it. This, I take it, is also the heart of the distinction between partisanship and factionalism that many defenders of partisanship seek to articulate, and this is also why the holist critique of partisanship (even in the extreme form it is usually taken to be offered by Rousseau) is not as wildly implausible as it might initially seem. 13 4. Order between parts Abstracting from particular interests in an attempt to develop principles of justice that regulate political conflict is only one way of tempering the potentially destructive power of unconstrained partisanship. An alternative way of thinking about how to bring order between parts is to arrange institutions in such a way that the interests of particular groups balance each other so that no particular one can prevail over the others. This proposal is at the heart of a second tradition of anti-partisanship which (as I shall argue in what follows) tends to assimilate factions and parties and resist unconstrained partisanship in the interest of stability more than justice. By exploring the reasons for this different kind of assimilation, we also learn to resist the temptation of celebrating unconstrained partisanship without reflecting on the background conditions under which partisanship can become a vehicle for promoting the public good rather than a manifestation of power which undermines it. The label "pluralist" which is often invoked to define this second line of thinking seems appropriate here.55 Pluralists are thought to be sceptical of the possibility of identifying suprapartisan principles able to regulate political conflict so that justice can oversee the order between parts. Their alternative is to reflect on the interaction between different parts of the political community such that the interests of different groups are institutionally represented without leading to destructive tensions. The existence of such parts is endorsed without much further questioning: it is assumed to be reflexive of the functional differentiation of groups in society, depending on the specific place of members of such groups in a wide mechanism of social cooperation, and on the specific interests attached to each. Although initially sceptical of the acknowledgment of the positive role of partisanship in this process, this second tradition is often thought to pave the way to a grudging acceptance of the productive role that conflict between parties might play if political rivalry is properly regulated.56 The distinction between factions and parties is here crucial too but, as I try to show, the reasons that make the distinction relevant in the first place risk being lost in an appreciation of partisanship which is blind to the pre-conditions under which partisanship can flourish and be distinguished from factions. Let me explain. One of the earliest and most forceful defences of pluralism in the context of an analysis of partisan conflict is Aristotle's account of regime types and his justification of the mixed constitution in book V of Politics. His assimilation of parties to factions occurs in the context of an argument which seeks to explore the causes of revolutions, the contribution partisan conflict 55 I owe the label to Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels : An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship., ch. 3 but for a discussion and the distinction between a pluralistic political system and the acceptance of party pluralism see also Sartori, Parties and Party Systems : A Framework for Analysis. pp. 12-16. 56 See Rosenblum, ch. 2 and 3. 14 makes to political stasis, and the way to guarantee the stability of a political system. Aristotle begins by targeting a certain idea of justice, justice as proportional equality, to illustrate the unavoidability of conflict between social classes when each of them interprets such an idea to favour its own perspective. As he emphasises "many forms of constitution have come into existence with everybody agreeing as to what is just, that is proportionate equality, but failing to attain it".57 It is interesting to notice here that Aristotle's critique is not so much that justice is an inappropriate value on which to focus in seeking to regulate social conflict, it is rather that interpretations over what justice requires end up fuelling such conflicts rather than providing a remedy to them. For example, democrats maintain that people are all free and also think that if people "are equal in one respect they are equal absolutely"; oligarchs, on the other hand, assume that if people are unequal in one dimension (e.g. their access to property) they are therefore "unequal wholly".58 These different beliefs lead to advocating different claims to rule, and "when each of the two parties has not got the share in the constitution which accords with the fundamental assumption that they happen to entertain, class war ensues".59 Order and stability in the political community can therefore be guaranteed only when the constitution mixes the representation of different groups and avoids making collective political decisions dependent on only one of them. Aristotle's analysis of political institutions is rooted in an account of society that emphasizes the functional differentiation of citizens and the relevance of identifying the type of constitution that suits the balance of different class interests. Particular forms of government (democracy, oligarchy, aristocracy, monarchy) correspond to different understandings of the ideal of equality that conforms to the wishes of different social classes, and can only be tempered if all of them find the right balance in a mixed constitution. Yet the assimilation of parties and factions here too confirms the preoccupation with class conflict resulting from the accumulation of power and wealth on the side of "the few" who run the risk of oppressing "the many". To regulate political conflict means to pluralise the sources of power in such a way that order and stability can be preserved whilst avoiding domination. The concern with civic order and the idea that partisan divides run the risk of fuelling destructive conflict unless they find a place in a political system that accommodates the humors ("umori") of differentiated parts of the citizenry is also central to Machiavelli's account of republican freedom (as it is to Vico after him60).61 Indeed, Machiavelli's argument that the conflict between the "humours" of different classes (the people and the great) and the tumults 57 Aristotle, Politics, trans. M.A. H. Rackham (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, [unknown] 1959). Book V, I, 2-3. 58 Ibid. 59 Ibid. 60 See also Giambattista Vico, Scienza Nuova Seconda (Bari 1953), vol. 1, p. 288. 61 The famous discussion appears in Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy., I, 4, 1. 15 resulting from them were one of the main causes that preserved the freedom of Rome is often interpreted as a proto-defence of partisanship without parties.62 But this might be too quick. What matters to Machiavelli is neither partisan conflict per se nor its containment through collective political arrangements accommodating a plurality of perspectives by appealing to a kind of abstract commitment to the public good. What matters instead is the defence of a plurality of class-specific forms of decision-making, able to limit abuses of influence by the wealthy (i grandi) and which can empower the people to oppose the tendency of political elites to dominate them.63 Indeed, Machiavelli's response to civic corruption is a defence of institutions with veto or legislative authority that exclude wealthiest citizens from eligibility, the combination of lottery and election in the appointment of magistrates, and a preference for trials which make political elites accountable to the entire citizenry.64 His remarks on the value of partisan conflict are generally sparse and heavily qualified. They do not even begin to contribute to a meaningful distinction between factions and parties; indeed both are seen as continuous to each other and as associative practices dedicated exclusively to the accumulation of private benefits. Machiavelli's distinction between divisions that harm republics and divisions that benefit them leads to warnings about partisan association simialr to those expressed by Rousseau in the famous passage of the Social Contract citing the Florentine Histories. The fact that a pluralist like him and a holist like Rousseau agree on this point should give us pause for thought. As Machiavelli puts it here: "it is true that one acquires reputation in two ways: either by public ways or by private modes". The latter entails "benefitting this or that private citizen, defending him from the magistrates, helping him with money, getting him unmerited honors, and ingratiating oneself with the plebs with games and public gifts. From this latter mode of proceeding, sects and partisans arise, and the reputation thus earned offends as much as reputation helps when it is not mixed with sects, because that reputation is founded on a common good, not on a private good".65 62 SeeIbid., I, 4, 1. For an analysis of the relevance of Machiavelli's account of partisanship see Sartori, Parties and Party Systems : A Framework for Analysis. p. 5, see also Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels : An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship. pp. 64-7. 63 See for a further discussion and defence of Machiavelli's model John P. McCormick, Machiavellian Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). 64 For further analysis and defence of each of these proposals in contrast to representative institutions and for a critique of the republican assimilation of Machiavellian democracy see Ibid., esp. chs. 3, 4 and 5. 65 Niccolò Machiavelli, Florentine Histories (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990) VII, 2. This distinction between private and public good is also central to Vico's reconstruction of republican conflicts: "Nelle repubbliche libere tutti guardano a' loro privati interessi, a' quali fanno servire le loro pubbliche armi in eccidio delle loro nazioni". See Giambattista Vico, La Scienza Nuova, vol. II, p. 108. 16 Although Machiavelli is often heralded as a pioneer of realism in political theory, a critic of abstract justice (which he did indeed drop from the list of cardinal virtues66), and a sceptic of moral values to which one might appeal in regulating conflict, it is useful to see that his concerns here resonate perfectly with those of Rousseau. Like many holists before and after him, the Machiavelli is also concerned with the corrupting effects of inequalities of honours, titles, wealth and influence, with the ability of the rich to manipulate public officials, and the use of bribery and clientelism as a way of obtaining private favours. Although it is difficult to find in his pluralist account of political community an appeal to principles of justice as a means to accommodate such conflicts, his analysis of civic order and his emphasis on republican freedom as a system of rule where the many are protected from domination by the few suggests a similar concern with the problem of inequality of influence and with the corrupting power of unconstrained wealth with which factionalism was identified. Without remedying such pathologies, Machiavell stressed, rule by the people struggles to become a meaningful vehicle of political participation and remains an instrument in the hands of powerful elites. 5. More than the sum of its parts? There is, I think, a reason for why neither Aristotle nor Machiavelli nor any of the other authors that defended pluralism prior to the consolidation of the modern representative system managed to distinguish clearly between factions and parties. None of them could really contemplate the idea of the state as an abstraction, an entity with a life of its own which both precedes and succeeds the particular groups that contend for the right to rule.67 Such an idea is crucial for understanding the problem posed by the equally abstract problem of a partisan but non-partial relation to the whole that is at stake in the distinction between factions and parties. The transition from an understanding of the well-ordered political community as an aggregate of functionally differentiated elements in society to an account of the state as an impersonal agency that is separate from both rulers and ruled required the modern concept of sovereignty. Only once such an idea was no longer alien among the different elements of society, the 66 See for a discussion of the role of traditional virtues in Machivalli, Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, vol. 2, Renaissance Virtues, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), esp. pp. 207-210. 67 For a discussion of this point and an excellent analysis of the relation between Aristotle's and Machiavelli's conceptions of political community see Harvey Mansfield, "On the Impersonality of the Modern State", American Political Science Review, vol. 77, no. 4, (1983), pp. 849-857. For a discussion of the transition in the use of the term state and the argument that Machiavelli plays a key role in the transition from the personal to the abstract idea of the state, see Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, vol. 2, cit. esp. pp. 186-212. 17 problem of the legitimate exercise of power by such impersonal force arose and demanded a solution through different articulations of popular sovereignty. The notion of parties as essential political agents indispensable to the formation of a general will through their non-partial contribution to articulating the good of the whole is inherently connected to this development. Justifying the central power of the state and legitimising the political institutions through which that power was exercised required mediating forces that could represent the will of the people in a way that both spoke to their concerns and commitments and connected them to a civic project which was no longer reduced to their partial interests or understood as the simple sum of its parts.68 For some this required bracketing partisanship altogether and designing political institutions in such a way that abuses of power by partisans could be tempered in a system of checks and balances involving mixed government or the separation of constitutional powers.69 For others, it involved assigning a positive role to parties either as vehicles of corporate representation and an essential chain linking civil society to the state70 or as associative practices necessary to articulate a public will in conformity with particular interpretations of the public good.71 A similar transition to the more positive understanding of parties, and an attempt to distinguish them from factions can already be observed in Montesquieu's pluralistic account of political order where a more sympathetic reconstruction of the role of parties in a political system begins to emerge. Located in the context of an analysis of the Roman republic similar to the one that we find in Machiavelli, Montesquieu also notes that the divisions that characterised the republic were far from detrimental to it, indeed they were necessary to maintaining its freedom. To ask that a free state should contain citizens that are both "so proud and brave" outside its boundaries and "moderate and timid" when it comes to domestic affairs is to ask "for impossible things", he suggested. Indeed, "each time people are seen to be in peace in a state that is called a republic, we can be certain that freedom is not there". However, while Machiavelli identified partisanship and factionalism and condemned both as detrimental to the public good, for Montesqueiu the former had a place in the republic, provided they contributed to a general harmony of parts. His point extended beyond the experience of republican Rome: "[W]hat we call union in a political body", he argued, "is something very ambiguous: the real union is a union of harmony that makes it possible that all parts, however opposed they may 68 As shown in ch. 1. See the discussion in Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels : An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship. ch. 2, esp. pp. 81-9. 70 See on this Hegel on, inter alia, the English reform bill and Rosenkranz. 71 The latter conception is the one whose story begins with Burke's appreciation of principled partisan with which I started this paper and that is further explored in ch. 3 of the book. 69 18 appear to us, concur to the general good of society, like dissonances in music concur to a general harmony".72 If Montesquieu was willing to grant that republics could flourish even in the presence of persistent partisan disagreement, provided that the relationship of parts to the whole was a harmonious one, it was because, similarly to Rousseau, he associated the general good with the development of an abstract entity like the state that could not be identified with the sum of its parts. Here too the holist and the pluralist critique overlap. The legitimacy of such entity could of course admit conflicts on matters of principle but such conflicts had to go beyond a mere confrontation of private interests and the attempt of particular groups to use the state to their advantage. Once the fundamental equality of all human beings was, if only in principle, acknowledged without restrictions to birth rank, religious affiliation or social status, the order of the whole depended on the existence of a mechanism for aligning a plurality of positions of principle and guaranteeing them universal representation while also tolerating difference. Only thanks to a similar mechanism grounded on associative practices through which individual views could be organised in conformity with a plurality of interpretations of the public good could the promise of popular sovereignty be effectively discharged. It is precisely from the necessity of this link between the universal and the particular, a link essential to rendering meaningful the idea of the people as sovereign, that the modern concept of partisanship became inextricably linked to the preservation of both justice and stability. This interpretation also explains why when conservative thinkers and apologists of the ancient régime later criticised modern conceptions of the party as vehicles for the expression of principled disagreement, it was because they longed for a return to a society based on the equilibrium between natural orders and unthreatened by the difference of opinions grounded on norms of reason. They saw exactly what was at stake in the acceptance of the modern idea of partisanship and they abhorred it for the way in which it elevated reason and principles to being the measure of the adequacy of any system of rules, undermining any natural hierarchies based on the authority of tradition. So the conservative German jurist and politician Julius von Stahl, for example, criticised political parties by distinguishing between two versions of a constitutional order: a traditional one based on historical political divisions emerging from functional divisions of the social organism (e.g. nobility, military, religious order) and a radical one based on natural rights and inspired by Rousseauian ideas that linked the political order to 72 Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu, Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Paris: Garnier Flammarion [1734] 1968), ch. IX, p. 59b, my translation (check Eng. translation). For further discussion of the idea of parties during the Enlightenment see Sergio Cotta, La Nascita Dell'idea Di Partito Nel Secolo XVIII (Bologna: Il Mulino, 1959). and Mario A. Cattaneo, Il Partito Politico Nel Pensiero Dell'illuminismo E Della Rivoluzione Francese (Milano: Giuffré, 1964). 19 norms of reason.73 Pluralism and partisan conflict based on principles, he thought, contained the seed for permanent revolution because one failed to understand society for what it was in its natural condition, and disrupted its organic equilibrium making the legitimacy of its institutions dependent on individual opinions allegedly based on reason. Conversely, when liberal defenders of the modern party system, responded to this critique, they insisted that the conservative ideal of society based on functionally differentiated groups and a traditional account of political legitimacy (one that was independent from principled views and involved the exchange of different reasons and opinions) had pernicious implications. Johan Kaspar Bluntschli, whose stark distinction between factions and parties we looked at earlier on, argued for example that Stahl's doctrine "divides the government from the governed and instigates each to consider the other its natural adversary and mutual sparring partner".74 The state was different from society: it could represent the latter but it stood above it, and it was precisely the acknowledgment of this superiority that allowed a plurality of parts to coexist and contribute to overall justice and order. If parties were essential to the life of a free state, it is because they accepted the partiality of their own position within it. If they distinguished themselves from factions, it is because they agreed that the perspectives they helped shape, articulate and channel were not reducible to the private interests of their associates but in accordance with general interpretations of the public good. That the state was abstract from society and superior to it, that it succeeded in realising the promise of popular sovereignty, that its system of rules could be shaped independently from the particular interests and needs of the different social groups from whose conflicts the state had emerged (e.g. the nobility, the clergy, regionalist groups, different economic classes etc.), were all propositions that many of course continued to doubt. Indeed, far from becoming obsolete, the party-faction distinction and the assimilation of one to the other, continued to be invoked each time that ideal, i.e. the ideal of the separation of the state from particular interest groups, was challenged. The spectre of factionalism continued to haunt partisanship anytime the state was accused of being no more than a committee for managing the affairs of any one of them (as with many socialists after Marx and Engels75) and anytime the purpose of government was declared to be the avoidance of permanent majorities (as in the Federalists' critique of the 73 See Julius von Stahl, Die gegenwärtigen Parteien in Staat und Kirche (Berlin: Hertz 1868). Bluntschli, Charakter Und Geist Der Politischen Parteien. p. For further analysis of the controversy between Bluntchli and Stahl, see Paolo Pombeni, Partiti e sistemi politici nella storia contemporanea (Bologna: Il Mulino 1994), pp. 108-112. 75 This awareness, rather than the affinity between socialism and holism, is (I think) what explains why the withering away of the state had to be the work of a party, a belief that remained unshaken for many authors from Marx to Engels to Lenin and Trotsky, and which only began to change with Bernstein. [need to say more on this] 74 20 link between factions and partisanship), and anytime the ideal of popular sovereignty was mocked for being just an idle aspiration. One might have responded here (as many liberals in fact did) that popular sovereignty was safe as long as the vehicle of representation of people's will were partisan conflicts of principle rather than factional disputes of interests. But the assertion that parties stood for the public good was also of little help since to make that assertion implied to take a stance on who was the public and what was the good (as Sieyes and the French revolutionaries soon discovered) thereby returning to the problem of how to render political conflict harmonious rather than destructive. As Madison emphasised in his reflections on the problem, "as long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves".76 And as long as this diversity of faculties gives rise to different claims to property, which in turn results in "different degrees and kinds of property", "a division of the society into different interests and parties" ensue.77 And once parties are formed following different views and concentrated around different leaders and groups, the animosities that accompany them render people "much more disposed to vex and oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good".78 In the end Madison agreed with Rousseau on the diagnosis of the problem: "the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property". He disagreed however on the remedy, believing it was both "impracticable and unwise" to seek to remove the cause of factional divides that were "sown in the nature of men".79 He argued that "relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects" and the more detailed prescriptions he provided are a familiar part of the pluralist institutional response to conflict between parts: separation of powers, due process, respect for fundamental rights, rule of law. Whether such remedies alone are sufficient to render conflict between partisans harmonious rather than destructive, or whether Rousseau was right to insist that without overall justice and attending to the causes of inequality, the general will would remain likely to err, is precisely what is at stake in trying to make a distinction between partisanship and factionalism. Indeed, it is worth emphasising here that despite the institutional remedies proposed by pluralists, a significant proportion of contemporary anti-party scepticism seems to stem from the sense that such institutional remedies limited to correcting the effect (rather than the 76 See Madison, Federalist Paper, nr. 10 Ibid. 78 Ibid. 79 Ibid. 77 21 cause) of inequalities are not enough, that without attending to the system of production of such inequalities, private influence will continue to corrupt political institutions. And when that is the case parties, like old factions, act in collusion with a political system that is dominated by modern oligarchies and ends up sacrificing "the many" to the interests of "the few". In the US such anti-party scepticism often takes the form of critiques to campaign finance, suggestions for improvement in electoral advertising or accusations of undue influence by corporate lobbyists on political elites.80 In Western Europe, recent analyses of the constraints that fiscal pressure by neo-liberal financial institutions places on democratic governments highlight the obstacles that political parties face in standing by anything other than the politics of austerity required of their states.81 As one author puts it, "more than ever, economic power seems today to have become political power, while citizens appear to be almost entirely stripped of their democratic defences and their capacity to impress upon the political economy interests and demands that are incommensurable with those of capital owners".82 Factionalism, understood in the classical sense as the unequal influence that those with more power and wealth exercise over the rest of the political community, continues to haunt principled partisan politics. The defence of parties as agents responsible for articulating particular interpretations of the public good seems more than ever vulnerable to being distorted by the pressure of external (in particular marketdriven) forces while the state is unable to incorporate these in a way that maintains the promise of popular sovereignty. The difficulties with coping with modern stasis, the crisis of contemporary liberal democracy appear to show, once again, the persistent challenge of making good on the partisan claim to be an agent irreducible to sectoral interes. 5. Conclusion The distinction between parties and factions is as important to assert the value of partisanship, as the assimilation between the two concepts is to detract from it. In this paper I tried to examine the roots of the distinction and the reasons for the assimilation, offering a brief excursus through some important statements of the relation between part and whole in key stages of both classical and modern political thought. My overview was necessarily coarse and 80 See for some critiques and further analysis Dennis F. Thompson, Just Elections: Creating a Fair Electoral Process in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), Issacharoff, Samuel, and Pamela S. Karlan. "Hydraulics of campaign finance reform." Tex. L. Rev. 77 (1998): 1705-1738, Overton, Spencer, "The donor class: campaign finance, democracy, and participation", University of Pennsylvania Law Review (2004): 73-118. [Need to add stuff from Piketty here]. 81 See Mair, Ruling the Void, Colin Crouch, Streeck etc. 82 Wolfgang Streeck, "The crises of democratic capitalism", New Left Review, vol. 71, pp. 5-29 (2011), p. 29. 22 selective since, rather than aiming to present a comprehensive analysis of the theories and profiles of different authors (which would in any case be impossible in the space of a short paper), I tried to focus on some key moments and texts through which to gain a more concrete impression of the issue at stake in emphasising or undermining the distinction between partisanship and factionalism. Advocates of partisanship, as we saw, tend to highlight the importance of principled disagreement, arguing that partisanship requires taking a non-partial approach to the public good and acknowledging the contribution that parts can make to the articulation of a general will. Sceptics, on the other hand, stress that the difference between factions and partisanship depends on the background circumstances under which different political groups operate. Their hostility to partisanship stems from two ways of thinking about potential remedies to destructive political conflict: an emphasis on justice in the case of holist critiques and an emphasis on order or stability in the case of pluralist ones. Both, as I tried to show, converge on their critique of accumulation of power, including wealth and office, and of its implications for the relation between different groups. Both place an emphasis on background constraints (prime among them the reduction of such inequalities of power) required for partisanship to become a vehicle for channelling the general will and really distinguish itself from factionalism. Therefore, while the distinction between parties and factions remains normatively promising and appears inextricable from the development of the concept of popular sovereignty, the reality of partisanship often fails to live up to this ideal. That is of course no reason for abandoning it, but nor should our attachment to the ideal render us blind to the importance of Machiavelli's distinction between divisions that harm republics, and divisions that are beneficial to them. As I tried to show, both pluralistic and holistic critics of partisanship might be right that in the absence of background constraints regulating political conflict, the ideal of active citizenship that is nurtured by partisan practices ends up being undermined rather than cultivated. To establish these constraints, one needs the help of a theory of justice as well as a different conception of the relation between civil society and the state, as many holistic and pluralistic critics of partisanship were right to point out. Showing how that can be done is the task of a different chapter. 23