Social mobility and VET - Cedefop

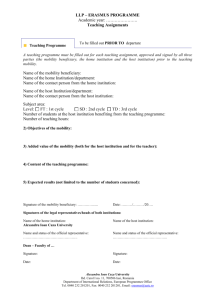

advertisement