Social Mobility : A Discussion Paper

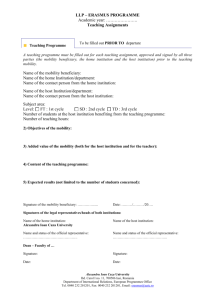

advertisement