06 Natasha Trethewey

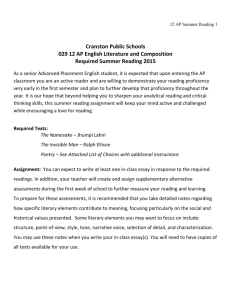

advertisement

Tuesday, February 28, 2006. "Poetry and the (M)uses of History: Narrating Women's Lives," Natasha Trethewey. MS. BRIZENDINE: Good morning. With great anticipation for our morning session, I'll offer the morning poem and then pass it on to Jill, who's doing the introduction. This poem is by Sharon Olds, and it's from her first collection, called "Satan Says." It's called, "The Mother." In the dreaming silence after bath, Hot in the milk-white towel, my son. Announces that I will not love him when I'm dead, Because people can't think when they're dead. I can't Think at first -- not love him? The air outside the window Is very black, the old locust Beginning to lose its leaves already... I hold him tight, he is white as a buoy And my death like dark water is rising Swiftly in the room. I tell him I loved him Before he was born. I do not tell him I'll be damned if I won't love him after I'm dead, Necessity, after all, being The mother of invention. MS. MUTI: It's a distinct pleasure to be able to introduce Natasha Trethewey this morning. We have been honored already by hearing a piece of her work which was dedicated to Bodie, but Natasha is the author of "Bellocq's Ophelia," which was printed by Graywolf in 2002, and "Domestic Work," from 2000, which won the 1999 Cave Canem prize. Her third collection, "Native Guard," is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Study Center, the National Endowment of the Arts, and the Bunting Fellowship program of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard. Her poems have appeared in such journals and anthologies as American Poetry Review, Callaloo, Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, New England Review, Best American Poetry 2000 and 2003. An associate professor of English and creative writing at Emory University, she is the Lehman-Brady joint chair professor in documentary studies and American studies at Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for this school year. Please welcome Natasha Trethewey. MS. TRETHEWEY: Good morning. It's a pleasure really to have this opportunity to present some of my work today. I'm going to read from all three of my collections, including the new book, Native Guard, and talk a bit with you about my theme, "Poetry and the (M)uses of History: Scaffolding, Restoration, and Monument." Writing about poetry, James Longenbach declared, "In addition to being many other things, poems are statements about our place in the world and like every other act of communication, they are historical." Similarly, in his 1919 essay, "Tradition and the Individual Talent," T.S. Eliot declared that the historical sense is indispensable to anyone who would continue to be a poet beyond his 25th year; and the historical sense involves a perception not only of the pastness of the past, but of its presence. Both of these writers are suggesting a kind of scaffolding that history provides for poems -- not only as knowledge of the literature of the past and its influence upon us, but also as an awareness of history, of past events and their lingering effects on the present. According to Joel Brouwer, however, in an essay entitled "Clio Rising," from Parnassus: Poetry in Review, "20th century American poets tend to write exclusively from their immediate experience and rarely admit a larger context, much less write on historical subjects." By history, Brouwer means collective social public history. Citing several poets who are exceptions: Rita Dove, Carolyn Forche, Michael S. Harper, Andrew Hudgins, Philip Levine, Ellen Bryant Voigt, he reminds us that they were only exceptions. "As a rule," Brouwer concludes, "the muse of history wields little influence over contemporary American poetry." In my own work, I see writing with the muse of history as a way of expanding subject matter, a way to move beyond immediate experience in order to discover the larger implications of our lives within the continuum of history, a way to enlarge the private moment by placing it in a broader context. And because I continue to be interested in the intersections and contentions between personal and public memory -- personal history versus public history -- I'm drawn to the ways in which public history can contextualize the exploration of issues of the self, of one's personal history. When I set out to write my first collection, "Domestic Work," I was interested in trying to narrate the life of my maternal grandmother, Leretta Dixon Turnbough, who was born in Gulfport, Mississippi, in 1916. She's an ordinary woman with what I think is an extraordinary story, particularly as it represents our American experience. That is, her history, to use the term that Ezra Pound coined, is highlighted by luminous details, those things which describe the transcendentals in an array of facts: Not merely significant nor symptomatic in the matter of most facts but capable of giving one a sudden insight into circumjacent conditions, into their causes, their effects, into sequence, and law." Thus, when I was narrating her life in poems, I focused on the work she had done, all the jobs she had held, from domestic worker to elevator operator, mother to hairdresser, drapery seamstress in a factory to a selfemployed seamstress in her own home. To under gird these poems as scaffolding, I did a foundational kind of historical research, mainly to locate each poem in the sequence within a particular historical moment. Sometimes this historical context is suggested by a date and/or a location, suggesting something about the lives of women and African-American workers in a certain time and place such as the Jim Crow South, the Civil Rights movement, the second wave of the feminist movement. The poems in "Domestic Work" also suggest a historical scaffolding through specific references, New Deal politics, segregation, the primitive blues. I'm going to start by reading just a bit now from Domestic Work, those poems that try to narrate my grandmother's life. This is "Domestic Work," 1937. All week she's cleaned someone else's house, stared down her own face in the shine of copperbottomed pots, polished wood, toilets she pull the lid to -- that look saying, Let's make a change, girl. But Sunday mornings are hers -- church clothes starched and hanging, a record spinning on the console, the whole house dancing. She raises the shades, washes the rooms in light, buckets of water, Octagon soap. Cleanliness is next to godliness... Windows and doors flung wide, curtains two-stepping forward and back, neck bones bumping in the pot, a choir of clothes clapping on the line. Nearer my God to Thee... She beats time on the rugs, blows dust from the broom like dandelion spores, each one a wish for something better. Speculation, 1939. First, the moles on each hand -That's money by the pan -And always the New Year's cabbage and black-eyed peas. Now this, another remembered adage, her palms itching with promise, she swears by the signs -- Money coming soon. But from where? Her left-eye twitch says she'll see the boon. Good -- she's tired of the elevator switch, those closed-in spaces, white men's sideways stares. Nothing but time to think, make plans each time the door slides shut. What's to be gained from this New Deal? Something finer, like beauty school or a milliner's shop -- she loves the feel of marcelled hair, felt and tulle, not this all day standing around, not that elevator lurching up, then down. Expectant. Nights are hardest, the swelling, tight and low (a girl), Delta heat, and that woodsy silence, a zephyred hush. So how to keep busy? Wind the clocks, measure out time to check the window, or listen hard for his car on the road. Small tasks done and undone, a floor swept clean. She can fill a room with a loud clear alto, broom-dance right out the back door, her heavy footsteps a parade beneath the stars. Honeysuckle fragrant as perfume, night life a steady insect hum. Still, she longs for the Quarter -- lights, riverboats churning, the tinkle of ice in a slim bar glass. Each night a refrain, its plain blue notes carrying her, slightly swaying, home. And this last one from Domestic Work comes out of one of my favorite stories that my grandmother ever told me, because it represents kind of ordinary acts of resistance that people do who perhaps were not part of marching on Washington or riding with the Freedom Riders, but people who find other ways to demand the kind of treatment that they deserve. This is “Drapery Factory,” Gulfport, Mississippi, 1956. She made the trip daily, though later she would not remember how far to tell the grandchildren -Better that way. She could keep those miles a secret, and her black face and black hands, and the pink bottoms of her black feet a minor inconvenience. She does remember the men she worked for, and that often she sat side by side with white women, all of them bent over, pushing into the hum of the machines, their right calves tensed against the pedals. Her lips tighten speaking of quitting time when the colored women filed out slowly to have their purses checked, the insides laid open and exposed by the boss's hand. But then she laughs when she recalls the soiled Kotex she saved, stuffed into a bag in her purse, and Adam's look on one white man's face, his hand deep in knowledge. It's true. He never checked their purses again. With my second collection, Bellocq's Ophelia, the muse of history took me in a different direction, both in terms of writing and research. Whereas I had sought to narrate a personal family story in Domestic Work, in Bellocq's Ophelia, I was interested in recovery work, or restoration. I wanted to restore to our collective memory the narratives of women whose stories had been lost or forgotten, left out of the historical record. I chose the unnamed women from E. J. Bellocq's Storyville portraits -- photographs of women in the red-light district of New Orleans, circa 1912. Thus, Ophelia is the imagined name of a very white-skinned black woman, mulatto, octoroon, or quadroon, who would have lived in one of the few "colored" brothels, such as Countess Willie Piazza's Basin Street mansion or Lula White's Mahogany Hall, which, according to the Blue Book, was known as the "Octoroon Club." When I first saw some of these photographs, I thought immediately there was one particular photograph that reminded me of John Edward Millais' painting of Ophelia from the cover of my ninth-grade “Hamlet” text, and this is how it began for me, trying to imagine a voice for the unnamed women in Storyville. So I'm going to read a little bit now from her diary that I imagine that she would have kept over a period of about a year while living in Storyville. Storyville Diary. One. Naming, en route, October, 1910. I cannot now remember the first word I learned to write -- perhaps it was my name, Ophelia, in tentative strokes, a banner slanting across my tablet at school, or inside the cover of some treasured book. Leaving my home today, I feel even more the need for some new words to mark this journey, like the naming of a child -- Queen, Lovely, Hope -- marking even the humblest beginnings in the shanties. My own name was a chant over the washboard, a song to guide me into sleep. Once, my mother pushed me toward a white man in our front room. Your father, she whispered. He's the one that named you, girl. 2. Father. February 1911. There is but little I recall of him -- how I feared his visits, though he would bring gifts: Apples, candy, a toothbrush and powder. In exchange, I must present fingernails and ears, open my mouth to show the teeth. Then I recite my lessons, my voice low. I would stumble over a simple word, say, lay for lie, and he would stop me there. How I wanted him to like me, think me smart, a delicate colored girl, not the wild pickaninny roaming the fields, barefoot. I search now for his face among the men I pass in the streets, fear the day a man enters my room both customer and father. Three. Bellocq. April 1911. There comes a quiet man now to my room -Papa Bellocq, his camera on his back. He wants nothing, he says, but to take me as I would arrange myself, fully clothed -a brooch at my throat, my white hat angled just so -- or not, the smooth map of my flesh awash in afternoon light. In my room, everything's a prop for his composition, brass spittoon in the corner, the silver mirror, brush and comb of my toilette. I try to pose as I think he would like, shy at first, then bolder. I'm not so foolish that I don't know this photograph we make will bear the stamp of his name, not mine. 4. Blue Book. June 1911. I wear my best gown for the picture -white silk with seed pearls and ostrich feathers -my hair is in a loose chignon. Behind me, Bellocq's black scrim just covers the laundry -tea towels, bleached and frayed, drying on the line. I look away from his lens to appear demure, to attract those guests not wanting the lewd site of Emma Johnson's circus. Countess writes my description for the book. "Violet," a fair-skinned beauty, recites poetry and soliloquies; nightly she performs her tableau vivant, becomes a living statute, an object of art -and I fade again into someone I'm not. 5, Portrait # 1. July 1911. Here I am to look casual, even frowsy, though still queen of my boudoir. A moment caught as if by accident -- pictures crooked on the walls, newspaper sprawled on the dresser, a bit of pale silk spilling from a drawer, and my slip pulled below my white shoulders, décolleté, black stockings, legs crossed easy as a man's. All of it contrived except for the way the flowered walls dominate the backdrop and close in on me as I pose, my hand at rest on my knee, a single finger raised, arching toward the camera -- a gesture before speech, before the first word comes out. 7. Photography. October 1911. Bellocq talks to me about light, shows me how to use shadow, how to fill the frame with objects -- their intricate positions. I thrill to the magic of it -- silver crystals like constellations of stars arranging on film. In the negative the whole world reverses, my black dress turned white, my skin blackened to pitch. Inside out, I said, thinking of what I've tried to hide. I follow him now, watch him take pictures. I look at what he can see through his lens and what he cannot -- silverfish behind the walls, the yellow tint of a faded bruise -other things here, what the camera misses. 9, Spectrum. February 1912. No sun, and the city's a dull palette of gray -- weathered ships docked at the quay, rats dozing in the hold, drizzle slicking dark stones of the streets. Mornings such as these, I walk among the weary, their eyes sunken as if each body, diseased and dying, would pull itself inside, back to the shining center. In the cemetery, all the rest, their resolute bones stacked against the pull of the Gulf. Here another world teems -- flies buzzing the meat-stand, cockroaches crisscrossing the banquette, the curve and flex of larvae in the cisterns, and mosquitoes skimming flat water like skaters on a frozen pond. 10. (Self) Portrait. March 1912. On the crowded street I want to stop time, hold it captive in my dark chamber -a train's sluggish pull out of the station, passengers waving through open windows, the dull faces of those left on the platform. Once, I boarded a train; leaving my home I watched the red sky, the low sun glowing -an ember I could blow into flame -- night falling and my past darkening behind me. Now I wait for a departure, the whistles shrill calling. The first time I tried this shot I thought of my mother shrinking against the horizon -- so distracted, I looked into a capped lens, saw only my own clear eye. In my new collection, Native Guard, the restoration of narratives that have been buried or forgotten -left out of public memory -- still undergirded my writing and research. Indeed, the title comes from the name of the first officially sanctioned regiment of African-American soldiers in the Civil War, the Louisiana Native Guards, mustered into service in September, October, and November of 1862, the second regiment stationed just off the coast of my hometown, Gulfport, Mississippi. During the war, they manned the fort on Ship Island as a prison for Confederate soldiers. Visitors to the fort today will see first the plaque placed at the entrance by the Daughters of the Confederacy listing the names of the Confederate dead, the men once interred there. Nowhere is a similar plaque memorializing the names of the Native Guards, and if tourists don't know to ask about the history of these black soldiers, most likely the park ranger will overlook this aspect of the fort's history in his tour, mentioning only that this was a fort taken over by Union forces, and that Confederate prisoners were kept there. Even the brochures leave out any mention that the troops stationed on the island were black. Their story has been erased from the landscape and from our public memory, as well. Even now, monuments all around the South serve to inscribe a particular narrative onto the landscape, while at the same time subjugating or erasing yet another. Thus, part of this collection is an attempt to reinscribe a narrative of those forgotten soldiers into our cultural memory, to create a monument in words to this aspect of our forgotten American history. But since we're talking about narrating women's lives here, I'm not going to read to you from that section of Native Guard. I'm going to read instead from the first section of the book, a monument in words, elegies to my mother. And finally, a few poems from the final section that stand as monument to my own relationship to the landscape and history of my South, as well as my place in it. As James Baldwin has written, "History does not refer merely or even principally to the past. On the contrary, the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do." And as Faulkner says, "The past isn't dead. It isn't even past." Before Amtrak took over, some of you must remember how lovely train travel could be. My mother loved train travel, and there was a train called the Southern Crescent and part of its route was between New Orleans and Atlanta. I think they still use the name, but the train is not as lovely as it used to be. This is "The Southern Crescent." In 1959 my mother is boarding a train. She is barely sixteen, her one large grip bulging with homemade dresses, whisper of crinoline and lace, her name stitched inside each one. She is leaving behind the dirt roads of Mississippi, the film of red dust around her ankles, the thin whistle of wind through the floorboards of the shotgun house, the very idea of home. Ahead of her, days of travel, one town after the next, and California, a word she can't stop repeating. Over and over she will practice meeting her father, imagine how he must look, how different now from the one photo she has of him. She will look at it once more, pulling into the station at Los Angeles, and then again and again on the platform, no one like him in sight. The year the old Crescent makes its last run, my mother insists we ride it together. We leave Gulfport late morning, heading east. Years before, we rode together to meet another man, my father, waiting for us as our train derailed. I don't recall how she must have held me, how her face sank as she realized, again, the uncertainty of it all -- that trip, too, gone wrong. Today, she is sure we can leave home, bound only for whatever awaits us, the sun now setting behind us, the rails humming like anticipation, the train pulling us toward the end of another day. I watch each small town pass before my window until the light goes, and the reflection of my mother's face appears, clearer now as evening comes on, dark and certain. This next poem has an epigraph from Robert Herrick's poem, "Faire daffadills, we weep to see you haste away so soone." “Genus narcissus.” The road I walked home from school was dense with trees and shadow, creek-side, and lit by yellow daffodils, early blossoms bright against winter's last gray days. I must have known they grew wild, thought no harm in taking them. So I did -gathering up as many as I could hold, then presenting them, in a jar, to my mother. She put them on the sill and I sat nearby, watching light bend through the glass, day easing into evening, proud of myself for giving my mother some small thing. Childish vanity. I must have seen in them some measure of myself -- the slender stems, each blossom a head lifted up toward praise, or bowed to meet its reflection. Walking home those years ago, I knew nothing of Narcissus or the daffodils' short spring -how they'd dry like graveside flowers, rustling when the wind blew -- a whisper, treacherous, from the sill. "Be taken with yourself," they said to me; "Die early" to my mother. This is a blues sonnet, “Graveyard Blues.” It rained the whole time we were laying her down; Rained from church to grave when we put her down. The suck of mud at our feet was a hollow sound. When the preacher called out I held up my hand. When he called for a witness, I raised my hand -Death stops the body's work, the soul's a journeyman. The sun came out when I turned to walk away, Glared down on me as I turned and walked away -My back to my mother, leaving her where she lay. The road going home was pocked with holes, That home-going road's always full of holes; Though we slow down, time's wheel still rolls. I wander now among names of the dead: My mother's name, stone pillow for my head. This next poem relies a little bit on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. This is "Myth." I was asleep while you were dying. It's as if you slipped through some rift, a hollow I make between my slumber and my waking, the Erebus I keep you in, still trying not to let go. You'll be dead again tomorrow, but in dreams you live. So I try taking you back into morning. Sleep-heavy, turning, my eyes open, I find you do not follow. Again and again, this constant forsaking. Again and again, this constant forsaking: My eyes open, I find you do not follow. You back into morning, sleep-heavy, turning. But in dreams, you live. So I try taking, not to let go. You'll be dead again tomorrow. The Erebus I keep you in -- still, trying -I make between my slumber and my waking. It's as if you slipped through some rift, a hollow. I was asleep while you were dying. My parents met at Kentucky State College, which is one of the historically all-black colleges and universities. My mother, from Mississippi, a black woman, and my father, a white man from Canada who got out a Guide to American Colleges and Universities and found one that he could afford and that would give him a track scholarship. He hitchhiked all the way down there, not knowing that it was a black college, but he stayed and there he met my mother. Of course, they couldn't get married in Kentucky, nor could they get married in Mississippi, my mother's home state. Just a few years ago, I think around 1996, the state of Alabama decided to put to a vote whether or not to remove the antimiscegenation laws from the books. They did remove them, but about 40-some percent of the population wanted to keep those laws on the books, so that, at least symbolically, parents like mine couldn't be legally married or people like me born legitimately. This is a ghazal, and it's called "Miscegenation." In 1965 my parents broke two laws of Mississippi; they went to Ohio to marry, returned to Mississippi. They crossed the river into Cincinnati, a city whose name begins with a sound like sin, the sound of wrong – mis in Mississippi. A year later they moved to Canada, followed a route the same as slaves, the train slicing the white glaze of winter, leaving Mississippi. Faulkner's Joe Christmas was born in winter like Jesus, given his name for the day he was left at the orphanage, his race unknown in Mississippi. My father was reading War and Peace when he gave me my name. I was born near Easter, 1966, in Mississippi. When I turned 33 my father said, It's your Jesus year. You're the same age he was when he died. It was spring, the hills green in Mississippi. I know more than Joe Christmas did. Natasha is a Russian name -though I'm not; it means Christmas child, even in Mississippi. "Southern Gothic." I have lain down into 1970, into the bed my parents will share for only a few more years. Early evening, they have not yet turned from each other in sleep, their bodies curved -- parentheses framing the separate lives they'll wake to. Dreaming, I am again the child with too many questions -the endless why and why and why my mother cannot answer, her mouth closed, a gesture toward her future: Cold lips stitched shut. The lines in my young father's face deepen toward an expression of grief. I have come home from the schoolyard with the words that shadow us in this small Southern town, peckerwood and nigger lover, half-breed and zebra -- words that take shape outside us. We're huddled on the tiny island of bed, quiet in the language of blood: the house, unsteady on its cinderblock haunches, sinking deeper into the muck of ancestry. Oil lamps flicker around us -- our shadows, dark glyphs on the wall, bigger and stranger than we are. This next poem is a pantoum, "Incident." We tell the story every year -how we peered from the windows, shades drawn -though nothing really happened, the charred grass now green again. We peered from the windows, shade drawn, at the cross trussed like a Christmas tree, the charred grass still green. Then we darkened our rooms, lit the hurricane lamps. At the cross trussed like a Christmas tree, a few men gathered, white as angels in their gowns. We darkened our room and lit hurricane lamps, the wicks trembling in their fonts of oil. It seemed the angels had gathered, white men in their gowns. When they were done, they left quietly. No one came. The wicks trembled all night in their fonts of oil; by morning the flames had all dimmed. When they were done, the men left quietly. No one came. Nothing really happened. By morning all the flames had dimmed. We tell the story every year. When I started writing this collection, as I mentioned, I was thinking about forgotten or buried histories, and I began doing the research about the Louisiana Native Guard. At the same time, 20 years later -- this is the 20th anniversary of my mother's death -- I was also writing these other poems, and I didn't think that I was writing the same book. I thought I was writing two different books, until something struck me that made me realize indeed why all these things were thematically linked, and that is that, 20 years later, I have yet to put a marker on my mother's grave. And we can talk later about all sorts of reasons that one might do such a thing, but when I started to write this collection, what I wanted to do was create a lyrical monument in words, as well, for her, because she had become part of the landscape's buried history, with nothing inscribing her presence. So this is "Monument." Today the ants are busy beside my front steps, weaving in and out of the hill they're building. I watch them emerge and -like everything I have forgotten -- disappear into the subterranean -- a world made by displacement. In the cemetery last June, I circled, lost -weeds and grass grown up all around -the landscape blurred and waving. At my mother's grave, ants streamed in and out like arteries, a tiny hill rising above her untended plot. Bit by bit, red dirt piled up, spread like a rash on the grass; I watched a long time the ants' determined work, how they brought up soil of which she will be part, and piled it before me. Believe me when I say I've tried not to begrudge them their industry, this reminder of what I haven't done. Even now, the mound is a blister on my heart, a red and humming swarm. I'm going to finish up with two poems. The first has an epigraph from Allen Tate's “Ode to the Confederate Dead” that reads, "Now that the salt of their blood stiffens the saltier oblivion of the sea." "Elegy for the Native Guards." We leave Gulfport at noon; gulls overhead trailing the boat -- streamers, noisy fanfare -all the way to Ship Island. What we see first is the fort, its roof of grass, a lee -half reminder of the men who served there -a weathered monument to some of the dead. Inside we follow the ranger, hurried though we are to get to the beach. He tells of graves lost in the Gulf, the island split in half when Hurricane Camille hit, shows us casemates, cannons, the store that sells souvenirs, tokens of history long buried. The Daughters of the Confederacy has placed a plaque here, at the fort's entrance -each Confederate soldier's name raised hard in bronze; no names carved for Native Guards -2nd Regiment, Union men, black phalanx. What is monument to their legacy? All the grave markers, all the crude headstones -water-lost. Now fish dart among their bones, and we listen for what the waves intone. Only the fort remains, near forty feet high, round, unfinished, half open to the sky, the elements -- wind, rain -- God's deliberate eye. And this last poem has an epigraph from E. O. Wilson that reads, "Homo sapiens is the only species to suffer psychological exile." "South." I returned to a stand of pines, bone-thin phalanx flanking the roadside, tangle of understory -- a dialectic of dark and light -- and magnolias blossoming like afterthought; each flower a surrender, white flags draped among the branches. I returned to land's end, the swath of coast clear cut and buried in sand: mangrove, live oak, gulfweed razed and replaced by thin palms -palmettos -- symbols of victory or defiance, over and over marking this vanquished land. I returned to a field of cotton, hallowed ground -as slave legend goes -- each boll holding the ghosts of generations, those who measured their days by the heft of sacks and lengths of rows, whose sweat flecked the cotton plant still sewn into our clothes. I returned to a country battlefield where colored troops fought and died -Port Hudson where their bodies swelled and blackened beneath the sun -- unburied until earth's green sheet pulled over them, unmarked by any headstones. Where the roads, buildings, and monuments are named to honor the Confederacy, where that old flag still hangs, I return to Mississippi, state that made a crime of me -- mulatto, half-breed -- native in my native land, this place, they'll bury me. Thank you. MS. LEE: Natasha, that was absolutely glorious. What a morning. And I think we owe her another round of applause for reading through the construction. You'll be happy to know that since Bruce is a control freak, he finally got them to stop it. MR. GALBRAITH: Actually, Kiki Johnson, a fellow executive director, part-time educator, helped me go down to the loading dock and fix that. MS. LEE: If you have questions, now is the time to ask them. I'll be on this side and Bruce will be on this side. SPEAKER FROM THE FLOOR: I noticed that you spoke of a couple of poems you wrote in some of these very complex line-repeating forms, and I noticed a number of contemporary poets are doing this, almost more so than traditional rhyme. Can you talk about why you use forms like the pantoum and why you think they're coming back, so to speak? MS. TRETHEWEY: Well, the "Blue Sonnet" and a few other things, "Elegy for the Native Guards," which I read, was also a 24-lined traditionally rhymed poem, but with the pantoum there's also the ghazal, there's also a villanelle that I didn't read. And then the sort of invented form in my poem "Myth" that just goes backwards. It occurred to me that what was important was to say that they need to say again, because I was trying to deal with grief, but also a transformation of grief, and so that by saying and saying again, my hope is that there is that kind of transformation. The way the line reads one way, when you hear it a second time, it moves away from that initial meaning to do something else. I also felt that it was about the need to speak certain histories into the air, those that might be lost or forgotten, and so in repeating those, repetition became a way to get those things into our cultural memory. SPEAKER FROM THE FLOOR: We're lucky that we work with kids who can relate to much of what you are sharing, but you picked the three toughest topics that our society doesn't seem to be interested in: History, race, and poetry. I'd be curious to hear how you view that, like salmon going upstream, how you view the work you care so much about in a society that doesn't seem to care about it. MS. TRETHEWEY: To value any of those things, yes, that is tough. Well, you know, Phil Levine once said, "I write what I have been given to write." And I feel very much the same way, that I can't shake off the burden of history, particularly because it does exist constantly in our contemporary moment, and I'm very afraid that if we are not constantly aware of history and its lasting effects, that we'll become a people adrift, without our historical sense. And it's true that not a lot of contemporary poets approach history. That there are lots of poems out there that are so deeply personal as to be cryptic, not accessible. And I'm always interested in exploring the self. You have to have a bit of that narcissism, I suppose, to even think that you'd want to listen. But trying to place that self in a historical context gives me a way of touching people across time and space. So I try very hard to get my students, for one, to do that. And in doing that, we might be able to help people like poetry more, too. I think what Bodie does, reading poems, is so wonderful because there has been a time where people stopped thinking that they could read a poem and enter the world of the poem, because there were poems that were so difficult as not to be accessible. And there's a lot of that still going on, coming out in programs right now. But when you think about Pinsky's favorite poem project, for example, he went around the country and found people who had had poems memorized that meant something to them, because they could understand them, because they spoke to some particular issue that was important to them, they helped us to empathize with other human beings. I think if we can remind people that poetry does that, then more people will come to poetry. Someone said to me, "Why do we teach poetry in the university or liberal arts college?" And he said, "I don't want the standard answer." And I thought, well, but the standard answer is one of the reasons that we do it. So I said, "Well, think about 9/11 and that outpouring of poems around the country, hundreds of thousands of poems, many of them bad, but all of them necessary, because people turned to poetry because they had no other language to describe what they felt about what happened." And I quoted the lines from William Carlos Williams' poem that say something like, "You can't get the news from poetry, but people die every day for lack of what is found there." And he said, "You don't really believe that, do you?" And I said, "Yes, of course I do." Because indeed, it's in poetry that we find empathy, compassion, a connection through communication to other human beings. And race. That's a real hard one, too. Because lots of people are tired of talking about it, but they're also tired because we haven't fixed it yet. I get students these days who have learned that somehow the Civil Rights movement fixed it, we took care of that in the '60s, and now we're done. And I don't think that that's the case. And so what I'm interested in is a little less issues of race and more about historical memory, cultural memory, cultural amnesia, historical erasure, because I feel that the stories that I tend to tell and to uncover belong to all of us. Not that the writing about the black soldiers means I'm writing about black history. I'm writing about American history, and I'm very interested in making sure that everyone understands that these narratives belong to all of us. They're all our history, all of our stories. Being from the South -- and I thought about this. Here I am in Charleston, a place that loves the Confederacy, reading my poems. And in my home state of Mississippi I do not want to erase those narratives. I just want to tell a fuller version of the history, to aggregate that story with another story, so we know more about ourselves as Americans. MR. GALBRAITH: I know you teach at one of our member schools in the summer. Can you talk about what you you're seeing in our young writers? Are there trends? What's important for you in a short time going to a group of young people? MS. TRETHEWEY: Well, on the one hand, you might see a trend, you know, the new ellipticals, lots of imagery that doesn't particularly connect to anything. Sometimes poems where there's no "there" there. But at the same time, I get a sense from the students that they want to be free to write poems that have some "there" there. Sometimes in MFA programs, it's hard, because you're a young graduate student and you're kind of -what's the word I'm looking for? But they're just trying to create these barriers around themselves, and people do this in poems. They use language, instead of as an act of communication, as a barrier to keep people out and to hide things about themselves. I think they like being given the freedom to actually risk sentimentality and to think about those things that have mattered and interactions between human beings for a long time. So I try to get them to write those poems that are historically situated. So if you want to explore family history, you do it by also exploring the place, time period, something that again contextualizes their experience and allows for that kind of deeply important communication that leads to empathy. Someone once said to me -- and I cringed when I heard this -- that he was offended by the idea that either the goal or the result of art could be empathy. And I thought, what do we have if we don't have that? MR. GALBRAITH: Will you share, if you would, what are you writing right now? Where is your "there"? MS. TRETHEWEY: I'm writing a little bit. I have a new book in mind, a new book project. At the very beginning of a book project, I do a lot of reading and research and storing up things for the poems. So I have written the first couple of poems in a new collection. MR. GALBRAITH: And where can we get your books? MS. TRETHEWEY: Just about anywhere, I think. The actual publication date of my new book is March 6, but it's out. It's in bookstores. You can order it. My first two books were on Graywolf, and Graywolf was a lovely press, but one of the things that Graywolf doesn't do is hard covers, because they don't think that poetry sells, to go back to what you were saying. So they only do paperbacks. And I ended up leaving to go to Houghton Mifflin for a hardcover, so this is my first hardcover. But it meant so much to me, because it is this monument to my mother, that it needed to feel more substantial. So if you will, you know, buy the hardcover. Shameless, I know. MR. GALBRAITH: Other questions? And where will you read next? What's coming up. MS. TRETHEWEY: Next I read at George Washington University. MR. GALBRAITH: Tell us about your role this year. You're in a special chair at Duke? MS. TRETHEWEY: Yes. Again, another sort of plus for poetry. Generally the Center for Documentary Studies brings in historians or documentary filmmakers, documentary photographers. They have actually brought in a couple of fiction writers. They had Alan Gurganus there last year. I'm the first poet to go there because the director, Tom Rankin, believes that poetry can do the work of documentary and history. So I'm very happy to be there and to be teaching a class called "Poetry and the (M)use of History." Students seem to be responding really well to it, too. SPEAKER FROM THE FLOOR: Can you share some thoughts about your mother's unmarked grave? MS. TRETHEWEY: What's so wonderful about poetry, it makes you discover things, and that's the best, when you're writing it. No discovery for the writer, no discovery for the reader. I have discovered a lot in trying to write those poems. It's going to sound really silly, but my mother was killed by her ex-husband 20 years ago. Not my father, but my stepfather. And when she died, she had his last name, and I did not want to put those words on a monument. And I can't believe how silly I was. And I didn't want to put my last name, my father's last name, because then that would have not acknowledged my brother, who was her second child, with the new husband, who had his last name. And I couldn't think of a way to do it until recently, I realized that I could say, you know, nee Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough, and just put the name that she was born with. And so now I plan to go do that. But it took me 20 years to deal with that, and it was about words. It was about language and the words that I couldn't inscribe her presence on the landscape with. MS. BENNETT: Bruce mentions you teach high school students, as well. And I'm interested in how young you teach, and what that experience is like, as compared to college graduate students. MS. TRETHEWEY: Well, actually the summer program that Bruce mentioned is a program for adults, but it's at Idyllwild, although I have done lots of programs with high schools in the past. I did a year-long project with Lafayette High School, in Lafayette, Alabama. It was one of those public schools that's on alert status, so they spent most of the time, as you have probably heard about, practicing for the tests and everything. But we chose students who were going to participate in a documentary project where they were going to write poems about their hometown, and to take photographs and to do some oral history. What I found was that they were so eager to do it. And I should tell you that Lafayette High School is a primarily black high school in a small town. This is a town that had what they called segregation academies, so that once integration happened, they built these other schools with Confederate names and sent the white children. What came out in these students writing about their hometown, I would ask them to write what you love about this place, what you hate about it. It's a really poor community, too. What they hated about it was that they weren't with the other children; that they very much wanted to be together, and they knew that there was something not right about them not being together. And they found countless ways in what they were doing to talk about that. MS. LEE: No more questions? MR. GALBRAITH: Do you have an encore? A closing poem? Do you have a goodbye sendoff? MS. TRETHEWEY: I have got a perfect one and I'll stand down here and read it. Just again about my obsession with history. This is “Pilgrimage.” Vicksburg, Mississippi. Here the Mississippi carved its mud dark path, a graveyard for skeletons of sunken river boats. Here the river changed its course, turning away from the city as one turns, forgetting, from the past -- the abandoned bluffs, land sloping up above the river's bend -- where now the Yazoo fills the Mississippi's empty bed. Here the dead stand up in stone, white marble on Confederate Avenue. I stand on ground once hollowed by a web of caves; they must have seemed like catacombs, in 1863, to the woman sitting in her parlor, candle lit, underground. I can see her listening to shells explode, writing herself into history, asking, what is to become of all the living things in this place? This whole city is a grave. Every spring – pilgrimage -- the living come to mingle with the dead, brush against their cold shoulders in the long hallways, listen all night to their silence and indifference, relive their dying on the green battlefield. At the museum, we marvel at their clothes – preserved under glass -- so much smaller than our own, as if those who wore them were only children. We sleep in their beds, the old mansions hunkered on the bluffs, draped in flowers – funereal -- a blur of petals against the river's gray. The brochure in my room calls this living history. The brass plate on the door reads, Prissy's room. A window frames the river's crawl toward the Gulf. In my dream, the ghost of history lies down beside me, rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm. MS. LEE: Well, after all that beauty, I really don't want to say anything, but I have to tell you that Bruce would like your name tags back, if you're leaving, and I wish I could say this in poetry. We need you to fill out your evaluation forms. Natasha, it just takes words away from the rest of us to hear you read, and we're so lucky that you said yes to our request. Thank you so much again. We have a 30-minute break now. Please come back at 10:15.