Culture and Altered States of Consciousness

advertisement

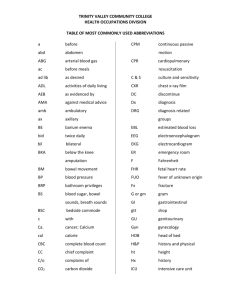

Culture and Altered States of Consciousness COLLEEN WARD In a colorful Hindu Temple in Penang, Malaysia, a devotee clad in a bright yellow doti (like a sarong, or loincloth) closes his eyes as the men and women around him chant and ask for blessings from the gods. The temple is enveloped in fragrant incense and as the chanting quickens and becomes louder, the man enters a trance state, turning inward and dissociating from the surrounding sounds, smells, and colors. At the appropriate moment, the attendant Hindu priest takes a skewer and pierces the man's right cheek, extending it through the mouth to the inside of the left cheek and exiting on the outside. The devotee does not flinch, he feels no pain, he does not bleed. The piercing continues. Small vels (needles with spade-shaped ends) are inserted at the forehead, the third eye point; larger hooks are placed in rows down the man's back. Still there is no evidence of pain or bleeding. When the piercing is complete, the devotee and his support group begin their pilgrimage to the Waterfall tem- Colleen Ward received her Ph.D. from the University of Durham, England. She has held teaching and research positions at the University of the West Indies, Trinidad, Science University of Malaysia, National University of Singapore, and University of Canterbury, New Zealand. She is currently the Secretary-General of the International Association for Cross-cultural Psychology and recently edited Altered States of Consciousness and Mental Health: A Cross-culturalPerspective (Sage,1989). For several years she was Book Review Editor of the Journal of Cross-CulturalPsychology. pie to make offerings to Lord Murugan. At the journey's end the hooks and skewers are removed, without evidence of bleeding, and although physically exhausted, the devotee reports feeling refreshed and contented. The experience was like "floating on air."' In a church in Trinidad, women are preparing for a period of "mourning." They are washed and anointed, dressed in white and given inscribed bands of cloth which are used to cover their eyes and ears. They are then "led to the ground," each given a place in the prayer room attached to the Spiritual Baptist church. For seven days and nights the women lie in mourning and are exposed to extended periods of darkness and isolation alternating with praying, chanting, singing, and clapping by animated visitors. The women "travel," experiencing vivid dreams and hallucinations concerning the development of their spiritual lives. The mourners describe the experience as "seeing without sleeping" and "jumping energy in the body." "I was no longer myself," is a common refrain. In a Mexican desert, a student of anthropology assumes an apprenticeship role to a Yaqui sorcerer. He experiments with alternative realities and various hallucinogenic substancesÑdatur inoxch, psilocybe mexicana. On one session he recalls, "All of a sudden I was pulled up. I distinctly felt I was being lifted. And I was free, moving with tremendous lightness and speed in water or in air. I swam like an eel. I contorted and twisted and soared up and down at will. I felt a cold wind blowing all around me, and I began to float like a feather back and 60 8/Culture and Altered States of Consciousness forth, down, down and down" (Castaneda, 1969, p. 157). The passages above describe the experience of altered states of consciousness (ASCs): trance and possession states, lucid dreaming, visions, and drug-induced states. These phenomena differ somewhat from the ASCs conventionally described in introductory psychology texts, which are more likely to include laboratory-based studies of nocturnal dreams, sensory deprivation, hypnosis, biofeedback, and perhaps meditation. Although more "exotic" altered states may seem unusual, even pathological, from a Western perspective, in other cultural settings these experiences are meaningfully integrated into everyday life. In fact, such ASCs are extremely common on a cross-cultural basis. Bourguignon and Evascu's (1977) anthropological study of 488 societies demonstrated that about 90% (437) displayed naturally occurring trance or possession states. This chapter considers cultural influences on various altered states of consciousness: drug induced states, hallucinations, trances, and spirit possession. On the most fundamental level, our genetic heritage and biological makeup determine the limits of our experience of consciousness. However, a cross-cultural perspective reveals that there is great diversity within these limits and that sociocultural influences pattern the evaluations and interpretations of these phenomena. THE NATURE OF CONSCIOUSNESS AND ITS CULTURAL INFLUENCES Consciousnessrefers to a general state of awareness and responsiveness to our external environment and internal mental processes. "Normal" consciousness is the state in which we spend the bulk of our waking hours. It is an active, directed, mentally alert state. As you are reading this chapter you are (probably) experiencing a normal, ordinary state of consciousness with focused attention and logical thought processes. Altered states of consciousness, by contrast, involve subjectively recognized, qualitative shifts in the typical pattern of mental functioning. ASCs are generally receptive mental states. You may have experienced them as daydreams, alcoholic intoxication or in the practice of meditation. ASCs are characterized by diffuse attention, paralogical (unorthodox) thought, and dominance of sensory experiences. The active and the receptive modes of consciousness represent innate human capacities; however, in Western cultures we value the primacy of active cognitive processing in normal waking consciousness. In line with evolutionary theory, it is widely accepted that this active mode of ordinary consciousness is adaptive and functional and serves to enhance the survival of the species. It simplifies and selectively processes information and guides and monitors our intra- and interpersonal actions. Although the receptive mode, characteristic of many altered states of consciousness, is viewed as deviant, mysterious, and occasionally pathological from a Western perspective, it also serves adaptive functions. Receptive mode ASCs often provide avenues for psychological growth and development; they are also commonly used as therapeutic mechanisms in ritual contexts. The fact that these ASCs are so widely pursued on a cross-cultural basis suggests that there may be a universal human need to produce and maintain varieties of conscious experiences. On the most basic level culturally shared views about consciousness pattern our experiences of "normal" and "altered" states of awareness. In On the most basic level culturally shared views about consciousness pattern our experiences of "normal" and "altered" states of awareness. In short, human potentials for various states of consciousness are culturally conditioned. short, human potentials for various states of consciousness are culturally conditioned. Through the learning process, a finite number of a wide range of potentials are fixed in a relatively stable way to produce an ordinary state of awareness. As we will see, however, we should guard against viewing "normal" states of consciousness as "optimal" or "best" (Tart, 1975). 8/Culture and Altered States of Consciousness The learning process similarly limits common alternatives or extraordinary states of awareness. You, for example, are unlikely to be able to attain the expanded states of consciousness available to long term practitioners of Yoga or to achieve spontaneously the altered states of awareness demonstrated by Fijian firewalkers. Furthermore, it is difficult, maybe impossible, for us to appreciate fully the subtle distinctions in consciousness that may be experienced in other cultures. For example, Sanskrit has about 20 nouns which translate into "consciousness" or "mind" in English simply because we do not have the vocabulary to distinguish different shades of meaning. In terms of cross-cultural comparisons, the repertoire of culturally patterned ASCs in Euro-Arnerican societies appears more limited and less ritualized than in many other cultures. This partially explains the concentration on rigourously controlled, lab based studies of biofeedback, drug and hypnotic states, and sensory deprivation in our psychology texts. In the tradition of experimental psychology, unusual states of consciousness are artificially induced in isolated laboratory sessions; the A X experiences are detached from the subjects' lives and lack real purpose or meaning. Cross-cultural perspectives on A X s , however, offer the unique opportunity to explore real world experiences in their natural environrnents~alteredstates of awareness that are common, perhaps everyday, experiences imbued with purpose and meaning. Hallucinations and trance and spirit possession receive particular attention here. CULTURAL VARIATIONS I N ASCS Hallucinations Hallucinations may be defined as "pseudoperception(s), without relevant stimulation of external or internal sensory receptors, but with subjective vividness equal to that aroused by such stimulation" (Wallace, 1959, p. 59). From this perspective most individuals have experienced hallucinations, and there are no cultures in which hallucinatory experiences are unknown. Despite the universal prevalence of hallucinations, however, there are aspects of the hallucinogenic experience which are dependent upon cultural learning. In the cross-cultural context hallucinations often occur in ritual settings and are associated with religious beliefs and tradi- 61 tions. As the surrounding events are usually public rather than private activities, the social context affects the phenomenology of hallucinations. In many instances, the experience of hallucination is a learned phenomenon with cultural values and social expectations providing the necessary cues for the ASC production and manifestation. Medical, psychological, and anthropological literature on hallucinations and mescaline use provides a compelling illustration of this point. Reviewing the literature in this area Wallace (1959) contrasted the hallucinatory experiences of Angloand native Americans in response to the ingestion of mescaline. The former group were generally "normal" white subjects in clinical trials. The latter were more regular users of peyote2 who consumed the substance in ceremonial contexts and in connection with religious rituals. The summaries of experiences are presented in Table 1. Overall, Anglo-Americans were more likely to display extreme variations of mood, to demonstrate a lack of social inhibitions and idiosyncratic hallucinations, and to experience an unsettling, unpleasant "split with reality." In contrast, native Americans reported religious ecstasy, hallucinations of a spiritual nature, therapeutic benefits, and an experience of a "higher order" of reality. The researchers concluded that the descriptions of the hallucinatory experiences were so different that informants did not seem to be talking about the same thing! Cultural views of ASCs also affect the interpretation of these experiences in relation to psychopathology. In Western psychiatry hallucinations are considered as defining features of psychotic disorders. This view, however, is not shared cross-culturally. Westermeyer and Wmtrob's (1979) study on the folk criteria for mental illness, "being insane in sane places," paints a different picture of hallucinatory experiences. In this research two transcultural psychiatrists surveyed 27 villages in rural Laos and identified 35 people who were labelled baa (insane). They then interviewed friends, families and neighbors of those individuals in order to isolate the defining criteria of insanity. The categories used by Laotian informants in their folk diagnoses were: (a) danger to self and others, (b) nonviolent but socially disruptive behavior, (c) socially dysfunctional behavior, (d) problems with speech or communication, (e) delusions, (f) mood disturbances, and (g) physical symptoms. Noticeably absent, however, was hallucination a s a defining characteristic of psychopa- 62 8 / Culture and Altered States of Consciousness TABLE 1 Responses to Mescaline Intoxication Anglo-Americans Variable and extreme mood shifts (agitated depression, euphoria, depending on stage of intoxication and personal characteristics) Frequent breakdown of social inhibitions display of "shameless" sexual, aggressive, behavior Native Americans Initial relative stability of mood, followed by religious anxiety and enthusiasm with tendency toward feelings of religious reverence and personal satisfaction when vision achieved, and often, also expectation of "cure" of physical illness Maintenance of orderly and "proper" behavior Suspiaousness of others present in the environment No report of suspiciousness Unwelcome feelings of loss of contact with reality, depersonalization, meaninglessness, "split personality" Welcome feelings of contact with a new, more meaningful higher order of reality, but a reality prefigured in doctrinal knowledge and implying more, rather than less, social participation Hallucinations largely idiosyncratic in content Hallucinations often strongly patterned after doctrinal model No therapeutic benefits or permanent behavioral changes Marked therapeutic benefits and behavioral changes (reductionof chronic anxiety level, increased sense of personal worth, moresatisfaction in community life) Excerpted from Wallace (1959) thologyÑdespit the fact that this was found in the majority of the 35 subjects! Trance and Possession Of all the exotic ASCs that may be examined, ritual possession holds the greatest fascination for Westem observers. Possession trance occurs in many forms and varied settings. In North America, possession by the Holy Spirit may be observed in charismatic Christian churches. In less familiar settings, ritual trance and possession may also be found in Shango and Voodoo practitioners in the Caribbean, devil dancers in Sri Lanka, temple mediums in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Korea, diviners in Sierre Leone, shamans in Thailand, Sasale dancers in Niger, Bantu rituals in South Africa, Candomble participants in Brazil, as well as Thaipusam devotees described in the opening passage. How do these ASCs occur? While the possession trance is usually displayed in a public ceremony, it often involves private preparation beforehand, such as fasting or purification rites. The ritual trance itself is typically induced by sensory bombardment-repetitive clapping, singing, and chanting. Burning pungent incense, repeated stroking of the skin, spinning or whirling in circles which precipitate disorientation to additionally facilitate trance induction. Ritual possession is a pub- lic event; as such, social expectationsare also instrumental in the ASC production. What does spirit possession look like? From external observations, the onset of possession is usually characterized by gross and uncontrollable body movements. Eyes appear glazed and still, sometimes only the whites showing. The possessed individual frequently takes on the demeanor of the possessing deity. They may become fierce and demanding or childlike and playful. The transformation can be quite dramatic. For example, in a Shango ceremony in Trinidad, I witnessed a man radically change movements, facial expression, voice- to a feminine persona when in the possession of a female deity. From the devotee's perspective, possession is experienced in various ways. Unusual bodily sensations are very common. Haitian Voodoo participants refer to the experience as being ridden like a horse. In other cults it has been likened to being struck with lightning or to floating on air. Although largely unaware of the surrounding environment and apparently disoriented, possessed individuals maintain enough control for safety. For example, in Afro-Caribbean cults possessed participants may dance "wildly" with swords or machetes without danger to self or others. Temporal and spatial distortion usually occur, and hallucinations may or may not be present. At the end of the possession 8 /Culture and Altered States of Consciousness ritual, it is common for individuals to experience a physical and emotional collapse. When they regain normal consciousness, they are generally unable to remember their activities during the possession episode. In adopting the role of the possessing deity, individuals who enter ritual trance may make demands on others or prophesize about the future. A well-known anthropologist once told me that an entranced Shangoist predicted her second marriage~whileshe was still happily married to her first husband! Many native healers render diagnoses and treatment plans when in the altered state of consciousness.Still others, such as temple mediums in Singapore, attempt to produce winning lottery numbers! Western observers have been quick to label these ASCs as pathological, describing them as various manifestations of hysteria, dissociative personality, epilepsy, and psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia. This assessment, however, fails to appreciate the cultural significance and evaluation of the ASCs (Ward, 1989). It is important to recognize that these altered states of consciousness have adaptive features on a number of levels: 1. Biological-There is evidence that the physiological mechanisms underlying ritual trance are similar to techniques used by psychiatrists to evoke emotional catharsis, the release, suddenly, of pent up psychological energy Ritual possession has been compared to psychiatric abreaction (emotional discharge) and is likely to involve "fine-tuning" in the autonomic nervous system (Sargant, 1973). 2. Psychological-Ritual possession offers a variety of psychological benefits. Participants generally report feelings of contentment, well-being, and/or rejuvenation after possession experiences. It is not uncommon for them to indicate alleviation of physical or psychological symptoms. 3. Social-During possession episodes there are also opportunities for individuals to indulge in a range of behaviors generally restricted in normal waking consciousness, such as dropping social inhibitions, making demands for favors, or assuming positions of authority. In addition, status and prestige in the community are acquired as a consequence of ritual possession. For example, a successful Thaipusarn pilgrimage, without evidence of pain or bleeding, indicates purity of heart. In the Shango cult, the 63 devotee's status in the community may mirror the possessing deity's status in a supernatural hierarchy. In Malaysia and Singapore, Malay bomohs and Chinese dang ki (temple mediums) are extremely well-respected and held in high regard by the general public. 4. Socio-cultural-Ritual possession functions to reinforce the religious beliefs of a community and to promote social cohesion among the group. In opposition to the popular view that these unusual altered states constitute psychopathology, then, there is strong evidence to suggest that they offer therapeutic benefits. CONCLUDING COMMENTS A cross-cultural approach offers a unique opportunity to expand our understanding of human consciousness. To benefit from this perspective, however, we must be open to new possibilities. Research tells us that our narrow definition of "normal" consciousness is not one which is shared cross-culturally. Different attitudes toward and experiences of hallucinations, dissociative episodes, trance, and spirit possession are found across cultures. Alternative varieties of conscious experience are encouraged, esteemed, and even formally institutionalized in diverse socio-cultural contexts. The ethnocentric tendency to regard unusual ASCs with suspicion and scepticism, a view held by Western scientists and laypeople alike, limits our understanding of normal and altered states of awareness. Contrary to popular theorizing, there is no evidence that these "exotic" ASCs are intrinsically pathological. Indeed, on many counts there is ample evidence that such altered states of awareness serve therapeutic purposes. There is a lesson here for us to learn: To understand any one ASC, it must be appreciated in its own terms and its appropriate sociocultural context; otherwise, we run into problems created by overgeneralizing about behaviors in other cultures. To understand ASCs more comprehensively, however, cross-cultural threads of our knowledge about these phenomena must be skillfully interwoven. Ultimately, we can only hope to achieve a deeper and more meaningful appreciation of human consciousness when we are able to shed our cultural blinders. As Tart (1975) aptly states: "We are simultaneously the beneficiaries and victims of our culture. Seeing things according to consensus reality is good for holding a culture together, but a 64 8/Culture and Altered States of Consciousness major obstacle to personal and scientific understanding of the mind" (p. 33). What do you think? FOOTNOTES 'Although the description is based on my fieldwork in Malaysia, the term "floating on air" comes from Ronald Simon's film of the same name. Veyote is the Spanish word for the tops (mescal buttons) of a small cactus (Lophophorn williamsii) which is used in Amer-Indian religious ceremonies for hallucinogenic effects. Mescaline is the psychedelic derivative obtained from the cactus. REFERENCES Bourguignon, E., & Evascu, T. (1977). Altered states of consciousness within a general evolutionary per- spective: A holocultural analysis. Behavior Science Research, 12,199-216. Castaneda, C. (1969). The teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui way of knowledge. Los Angeles: University of California Press. Sargant, W. (1973). The mind possessed. New York: Lippincott. Tart, C. (1975). States of consciousness. New York: Dutton & Co. Wallace, A.F.C. (1959). Cultural determinants of response to hallucinatory experience. American Anthropologist, 1,58-69. Ward, C. (Ed.) (1989). Altered states of consciousness and mental health: A cross-cultural perspective. Newbury Pk, CA: Sage. Westermeyer, J., & Wintrob, R. (1979). "Folk" criteria for the diagnosis of mental illness in rural Laos: On being insane in sane places. American Journal of Psychiatry, 136,755-761.