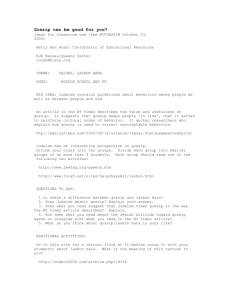

Consumption, Gossip and Power:

advertisement