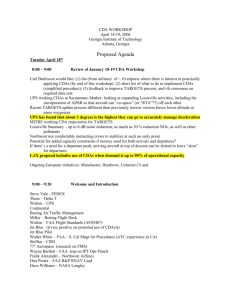

Talking Paper - Dayton Aerospace, Inc.

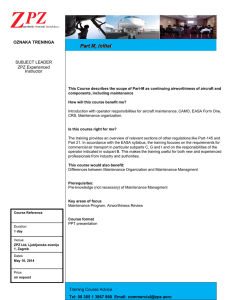

advertisement