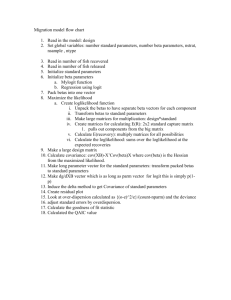

Testing Factor Models on Characteristic and Covariance Pure Plays

advertisement