Publication Articles - Texas Music Teachers Association

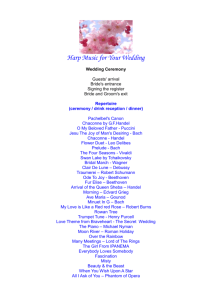

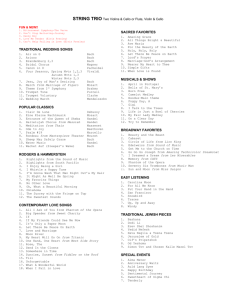

advertisement