DOES AN INSURED HAVE A DUTY TO MITIGATE DAMAGES

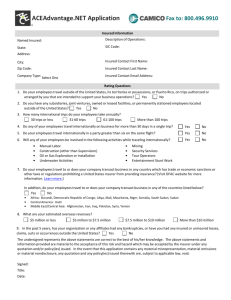

advertisement