Triple X syndrome Trisomy X FTNW

advertisement

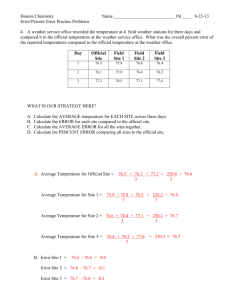

Triple X syndrome also called Trisomy X rarechromo.org Triple X syndrome or Trisomy X Triple X syndrome (Trisomy X) is a genetic condition that only affects females. Girls and women with triple X syndrome have an extra X chromosome. Most people have 46 chromosomes, made up of tightly coiled DNA along which are the genes that instruct the body to develop and work properly. There are twenty-two pairs of chromosomes numbered 1 to 22 plus two sex chromosomes. In males the sex chromosomes are different: one is called X and one is called Y, so male chromosomes are usually described as 46,XY. Females usually have two X chromosomes and are described as 46,XX. Females with triple X syndrome have an extra X chromosome, so three in all. Triple X syndrome is sometimes called 47,XXX. We suggest that you use the full name Triple X syndrome as a search term on the internet. Alternatively, use Trisomy X. How common is Triple X syndrome? Around one girl in 1,000 has triple X syndrome. Based on this figure, in 2013 around 3½ million girls and women in the world are estimated to have an extra X chromosome. The great majority of them - perhaps 90% - never know that they have this extra chromosome. In the United Kingdom an estimated 31,800 females have triple X syndrome. In the US, an estimated 158,500 girls and women have triple X syndrome. In Australia around 11,600 females have triple X syndrome. When this information guide was written, Unique had over 137 members with triple X syndrome, aged from birth to 66 years old. There are other internet-based support groups specific to triple X syndrome. Some of them are listed on the back of this information guide. Mosaic Triple X syndrome Most women and girls with triple X syndrome have one extra X chromosome in the cells of their body. But quite a few girls and women have some cells with three X chromosomes and some with a different number of X chromosomes. This is known as mosaicism. Mosaicism can change the effects of triple X syndrome. These are the most frequent types of triple X mosaicism: 47,XXX/46,XX - Generally speaking, the effects of triple X will be milder, lessened by the presence of cells with the normal number of X chromosomes in some tissues of the body 45,X/47,XXX - This is essentially a mosaic form of Turner syndrome (TS), although the presence of cells with an extra X chromosome will generally moderate the TS features, especially if the ratio of 47,XXX cells to 45,X cells is high 47,XXX/48,XXXX Generally speaking, a girl or woman with this chromosome make-up will show aspects of both triple X syndrome (47,XXX) and tetrasomy X (48,XXXX). But as there is great variation in people with both conditions, girls and women with this form of mosaicism will also show a lot of variation. Unique has a separate guide to tetrasomy X. 2 Information about Triple X syndrome We know about triple X syndrome from studying girls and women who are known to have an extra X chromosome. In the 1960s almost 200,000 newborn babies from six centres worldwide had their chromosomes checked and those with triple X syndrome were followed up, in some places for more than 20 years. These girls and women are the source of most of what we know about triple X syndrome. The information from studying these girls as they grew up is unbiased because they were not diagnosed because they had problems. However, the numbers of girls followed up, especially into adulthood, are very small. For instance, in the Edinburgh centre only 16 women with triple X syndrome were still being studied by 1999. Social conditions have also changed a lot since the 1960s. Today, there are two ways that the extra chromosome is usually discovered. A pregnant woman has an amniocentesis, usually because she is an older mother: information from this group is also unbiased. A baby, girl or woman is investigated because of development or health problems: information from this group is skewed towards abnormality. It doesn’t show a fair picture of how triple X syndrome generally affects girls and women. But this information can still be helpful to families. Sources The information in this guide comes from the medical literature, from a recent study in the United Kingdom on the development of children with an extra sex chromosome (DIESC study), from Unique and from a survey of 43 families diagnosed before birth by the UK Triple X syndrome support group in collaboration with the late Dr Shirley Ratcliffe, in her time an authority on sex chromosome anomalies. References The text contains references to articles in the medical literature. The first-named author and publication date are given to allow you to search for the abstracts or original articles on the internet in PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed). If you wish, you can obtain articles from Unique. The guide refers particularly to A review of trisomy X (47,XXX) by Dr Nicole Tartaglia and colleagues and published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases in 2010 (doi: 1186/1750-1172-5-8). This is an invaluable and comprehensive guide and is available to everyone on the internet via PubMed. The guide also refers to Triple X syndrome: a review of the literature by a psychiatrist, Dr Maarten Otter and his colleagues and published in the European Journal of Human Genetics in 2009 (doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.109) (Otter 2009). 3 Typical features of Triple X syndrome Triple X syndrome affects individual girls and women differently. Some are scarcely affected, if at all, while others can have obvious and significant problems. These are the most typical features: • • • Speech delay • Vulnerability to difficulties in making friends at school age, normalising in adolescence • Increased vulnerability to behavioural and social stress • Mild delay in physical development Need for some extra learning support Rapid growth at 4-13 years, with especially long legs What causes Triple X syndrome? In most cases it’s not known what causes triple X syndrome. Girls usually inherit one X chromosome from their father and one from their mother. Girls with triple X syndrome can inherit their extra X chromosome from either parent but it’s more common from their mother. Early studies showed that the average age of the mother of a baby with triple X syndrome is 33, which is higher than average (Otter 2009). Even so, most babies with triple X syndrome are born to younger mothers. When eggs form, chromosome pairs usually divide so that each cell has a single X chromosome. Mistakes during cell division can leave two X chromosomes in the egg cell. This type of mistake is known as non-disjunction. Fertilised by a single X-carrying sperm, the egg will then develop into a baby with three X chromosomes. In around one fifth of all cases, a mistake occurs just after fertilisation during the copying of the early cells that will become an embryo, then a fetus and then a baby (Tartaglia 2010). Egg cells Cell with no Cell with extra X chromosome Normal cells with one X chromosome 4 Was it my fault? No. Triple X syndrome is a random event. No environmental, dietary, workplace or lifestyle factors are known to cause sex chromosome variations such as triple X syndrome. There is nothing you did before you were pregnant or during pregnancy that caused triple X syndrome to occur and there is also nothing you could have done to prevent it. Diagnosis Most girls and women with triple X syndrome never know that they have an extra X chromosome. When it is found, in pregnant women, the extra X chromosome is usually discovered during prenatal tests for other chromosome disorders such as Down’s syndrome. The extra X chromosome is sometimes found after birth when chromosomes are examined because of concern about a girl’s unusual physical features or development. In girls with triple X syndrome, the signs may be so subtle that the diagnosis is reached late. Outlook Most girls and women with triple X syndrome lead normal lives. They go to mainstream schools, have jobs and children and live into old age. There are certain differences between girls with triple X syndrome and girls with two X chromosomes. Most of the differences are what you would find as part of normal variation between individuals. 5 Babies Babies with triple X syndrome usually look perfectly normal at birth with nothing to suggest the extra X chromosome. A typical baby with 47,XXX weighs on average 3kg (6lb 10oz), that is 400-500g (14-18oz) less than a baby with two X chromosomes. Typically, the head is a little smaller than average (Otter 2009). The tone of the muscles may be slightly low so the baby feels rather floppy to hold. On average, babies smile at two months, with the earliest smiling at one month and the latest at six months (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Most babies are breastfed and in a survey by the Triple X syndrome group none needed tube feeding. On the move Girls with triple X syndrome may be a little late starting to crawl and taking their first steps. But there’s a huge variation between individuals. Girls with triple X syndrome typically crawl around 10 months (range five - 20 months) and take their first steps around 16-18 months but the known range is nine to 36 months (Triple X syndrome group 2006; Tartaglia 2010). Despite any initial delay, by school age, many girls with triple X syndrome are taking part in sports and team sports (DIESC 2009; Linden 2002; Pennington 1980). Underlying the slight delay are motor coordination problems in many (Otter 2009) and continuation of low muscle tone and bendy joints in some (Triple X syndrome group 2006; Tartaglia 2010). Among 24 children aged 0-5, a quarter of the girls had low muscle tone, affecting different parts of the body. Of four children with unusually bendy joints and low muscle tone, three were late walkers, taking their first steps after 18 months. Among a group of 25 girls aged 6-10, ten had hypotonia (low muscle tone), again affecting different parts of the body. In the 11-16 age group, 3/17 girls had slack abdominal muscles, giving them a protruding stomach (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Other studies have shown that as a group, girls are more easily tired (Otter 2009). Girls on the move top left at 5 years bottom left at 9 years centre at 7 years right at 11 years 6 Some difficulties with planning movements have been observed and these may create problems in complex muscle sequences such as those needed for sport. All the same, girls generally find that both gross motor (movement) and fine motor (hand-eye) coordination appear to be well preserved (DIESC 2009; Otter 2009; Salbenblatt 1989). Further, some studies have reported well-preserved fine motor coordination with good sensory motor integration (Linden & Bender 2002; Salbenblatt 1989; Robinson 1990). Twenty-five per cent of families told the DIESC researchers that their daughter was good at sport. Families told the researchers that if their daughters persevered with activities, they built up muscle strength and enjoyed activities such as swimming, dancing and horse riding. Nonetheless, girls found both fine and gross motor skills more difficult than their siblings did. Their handwriting may be messy or they may be uncoordinated or clumsy when using cutlery. Everyday behaviours Many girls with triple X syndrome take longer than average to be potty trained. They achieve this on average around 36 months (range 12 months to 10 years) with the great majority clean and dry by four years. Night-time dryness emerges typically in the fourth year, on average by 44 months, but the range is broad, from 18 months to over six years (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Sixteen years old The DIESC study found that girls with triple X syndrome were as good as their sisters at understanding money, time and play and leisure skills (DIESC 2009). Girls with triple X syndrome find many everyday tasks a little more difficult than their siblings but still perform within the expected range for their age. 7 Learning to talk Girls with triple X syndrome are typically a little slow to start speaking but still achieve within the expected range for their age. Typically, they say their first words around or shortly after their first birthday and their first sentences at or around their second birthday. Around half of girls show a delay in both understanding and speech and three-quarters of school-age girls have some difficulty with language. Studies suggest that 40-90 per cent of girls benefit from speech therapy. The best age to start speech therapy isn’t certain, but some say the earlier the better as early intervention can do no harm and may do some good (Linden 2002; Triple X syndrome group 2006; Otter 2009; Tartaglia 2010). Girls can find it difficult to retrieve words whether they are under a time constraint or not. Compared with their brothers or sisters, they use less complex syntax at a similar age and have a narrower grasp of meaning. Other aspects of communication, such as interests and non-verbal communication, appear to be unaffected by the extra X chromosome. The DIESC study found that girls with 47,XXX seem to find structural aspects of language more difficult, such as expressing themselves or understanding complex sentences. They didn’t have particular difficulties with aspects of language such as when to say things appropriately, taking turns and so on. Five years old Families report that their daughters are chatty but have a slightly more limited vocabulary than their siblings (DIESC 2009). Among 25 girls aged 6-10, almost half had speech delay. Out of 17 girls aged 11-16 only two were still receiving speech therapy (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Families at a Unique study day said that singing, repetition and music with a beat help speech. Some said that their daughters were hypersensitive to loud noises (Unique). School and learning Almost 70 per cent of girls with 47,XXX do fine at mainstream school, although most have some 1:1 teaching, usually for reading, although they may also need extra help in other subjects such as maths. The need for support may be obvious in the early years and it seems that if proper support is provided in the early years, educational levels are maintained during adolescence (Otter 2009; Triple X syndrome group 2006). The DIESC study found that 55 per cent of girls diagnosed before birth or before their first birthday had no problems at all at school. Of those diagnosed later (so more likely a biased sample), eighteen per cent had no learning difficulties at school. Twelve years old Most families say that their daughter enjoys school and many girls particularly enjoy maths and spelling. Just over 30 per cent of girls diagnosed before birth had a statement of special educational need but very few girls attended 8 special units or schools. This suggests that any difficulties they experience with learning are relatively mild (DIESC 2009). Overall, the DIESC study found that around 14 per cent of girls whose 47,XXX was diagnosed before birth or in the first year of life had a statement of special educational needs. Of those diagnosed later, 50 per cent had a statement of special educational needs. Girls with triple X syndrome typically have slightly more difficulty learning to read and write than usual. 1:1 teaching usually overcomes this difficulty and the DIESC study found that girls showed relatively good reading and writing skills. However, there may be subtle differences. Girls with triple X syndrome do seem to have particular difficulties concentrating and paying attention but they do not translate this difficulty into fidgeting or hyperactivity. Rather, their concentration may easily wander and they may have more difficulties than expected seeing tasks through to a conclusion (DIESC 2009; Tartaglia 2010). Girls with triple X syndrome also often have difficulty remembering what they have learned recently and may need information repeated more times to fix it in their memory (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Graduation Day - almost 70 per cent of girls do fine at school When girls with triple X syndrome have done intelligence tests, they have usually scored around 20 points lower than others on verbal tests and around 15 points lower on performance tests. Around 60 per cent of girls have an IQ over 90 but there’s a tendency to do worse on verbal scores and only around 30 per cent of girls score over 90 on verbal IQ tests. A difference of this size is common between brothers and sisters. But a girl with triple X syndrome is likely to be aware that she struggles a little more with some aspects of learning. This can affect her self-esteem but will generally improve once she leaves school (Otter 2009). School and friends Girls with triple X syndrome are described by their families as very loving and kind. They are caring, especially with animals and younger children. Many are described as having a great sense of fun and most have close friends. Their social skills are generally within the range expected for their age – they are aware of others, have good manners, cope with change and are aware of danger with only slight differences between their behaviour and their brothers and sisters. They also show good interpersonal skills, good understanding of emotions and knowledge of how friendship works. But some parents have commented that their daughter tends to smother others (DIESC 2009). Some girls with triple X syndrome do find it difficult to make friends at school. This difficulty can start early, in the pre-school years, and girls with triple X syndrome can appear immature. 9 The early difficulties with language may underlie the difficulties that some girls face in making friends. They generally have good relationships with adults. But 11/25 girls aged 610 had problems relating to other Good interpersonal skills children and 16 girls in this age group were unusually shy (Triple X syndrome group 2006). They may lack self-confidence because they know that they struggle a bit more to do things that others do easily. But they appear to Loving and kind overcome these difficulties and are reported to be popular and well-liked. All the same, in the DIESC study, a small group of parents reported being worried about their daughter being bullied at school. Around age 11 appears to be a particularly difficult time for socialisation, as girls may still play in a way that their peers might find childish. As they mature, their social skills improve as is also suggested by better social skills in older girls, especially if diagnosed early in life (DIESC 2009; Otter 2009; Linden 2002; Bender 1995). Meanwhile, families comment that stressing their daughter’s strengths (such as her beautiful, long legs) helps their confidence. Will growth be normal? Typically, girls grow at a normal rate until four years, then fast until puberty. Some girls with triple X syndrome grow more rapidly than their classmates and friends between four and eight years, especially their legs. They are typically in the top quarter of girls for height. But any increase in weight is less than in height, so they are typically slim. They have a delayed bone age until 7-10 years. These differences become less obvious in adolescence (Otter 2009). Growing pains were reported by 12/20 families at a Unique study day (Unique). Long legs and slim: 6 years (left) and 12 years (right) 10 Growing up: up: 15 years (left); 17 years (centre left); 18 years (centre right and right) Puberty and periods Puberty usually starts around the time expected, with breasts developing from 11 years (perhaps six months later than in other girls) and periods starting between 10-15 years. Behaviour and mood There’s a conflict of evidence over some aspects of behaviour in girls and women with triple X syndrome. The DIESC 2009 study found no evidence of greater oppositional behaviours in girls with 47,XXX diagnosed early or before birth compared to their sisters. The picture is more complicated for anxiety: girls diagnosed late were more anxious than their sisters, and older girls more so than younger girls, although few girls (whether diagnosed early or late) scored above the cut-off for clinical concern for anxiety. Other researchers found that girls and women with triple X syndrome can become easily anxious, with social avoidance, separation anxiety and generalised anxiety figuring prominently. Social immaturity relative to their peers is also found which, together with their other difficulties can make some girls vulnerable to social pressures and victimisation (Bender 1999; Tartaglia 2010). Some researchers have found high numbers of women with depression (Bender 1999; Harmon 1998). There is a slightly increased incidence of attention difficulties, attention deficit disorder and conduct disorder (Robinson 1990; Pennington 1982). 11 The DIESC study also found that girls with triple X syndrome were more likely to show some behaviour and hyperactivity difficulties, but only 15 per cent of them scored at levels that would cause any concern. Hyperactivity was only found in this study in the girls who were diagnosed after their first birthday (that is, a biased group) and in this group the difficulties did seem larger for older than for younger girls. They found that girls were more prone than their siblings to difficult behaviour such as temper tantrums, stubbornness and being easily led (DIESC 2009). A number of studies have found that girls were particularly sensitive to stress in family life. They needed parental support for longer than other girls (Otter 2009). Psychological disorders have been shown to be more common in adulthood but respond well to standard treatments (Otter 2009). This may be borne out by the findings of the Triple X syndrome group who found that two adolescents/13 reported depression (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Data from the DIESC study also showed that girls with triple X syndrome are more likely than their sisters to be emotional (mood changes, temper outbursts, frequent crying, many worries, often unhappy) and those diagnosed after their first birthday (the biased group) also showed a tendency towards psychosomatic difficulties, such as feeling tired all the time or complaining a lot about aches and pains. Medication treatments are the same as for other girls and women but low starting doses are recommended (Tartaglia 2010). A Triple X syndrome group survey showed that 16/43 girls were shy when they started nursery or first school. The survey also found that 10/25 girls aged 6-10 liked rituals or disliked changes to their routine (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Adulthood Many women with triple X syndrome go on to further and higher education after school. They go on to hold jobs at all levels in society. From what we know so far, many go on to jobs of a practical and caring nature, including caring for children and older people. There is some evidence of adults having problems in establishing satisfying relationships and some women have continuing issues of low self-esteem (Otter 2009). Having children It seems that most women with triple X syndrome have no problem in becoming pregnant and can expect to have healthy children, although no direct studies of fertility in triple X syndrome have been carried out. The extra X chromosome is not usually passed on to their children (Tartaglia 2010). A woman with triple X syndrome can ask to be referred for genetic counselling before she is pregnant. If she wants prenatal tests on her baby, they should also be offered. However, the triple test and early pregnancy blood tests do not show whether a baby has an extra sex chromosome, so an invasive test would be needed such as chorionic villus sampling or an amniocentesis (where cells from the developing placenta or the fluid around the baby are examined) (Otter 2009). Early menopause Premature ovarian failure (POF) seems to be somewhat more common than in the general population. Cases have been described in the medical literature ranging in age from 19 to 40 but no-one knows yet how common POF is in triple X syndrome. In a high 12 percentage of the cases the woman with POF also has an autoimmune disorder (Otter 2009; Tartaglia 2010). When this occurs, a woman in her 20s, 30s or early 40s starts having irregular periods and may miss them altogether for a few months. The supply of eggs to the ovaries stops before the expected age for menopause and the ovaries stop functioning normally. The reason why this might happen in some women with triple X syndrome isn’t known for certain but it’s theoretically possible that since half the eggs of a woman with triple X syndrome would be expected to have an extra X chromosome they are perhaps sidelined. 13 Notes on physical and clinical issues Non-organic abdominal pains A quarter of girls and young women experienced abdominal pains for which no physical cause could be found (Otter 2009). This was confirmed in the Triple X syndrome group survey, who found stomach pains reported by 14/43 families (Triple X syndrome group 2006). But the DIESC study threw a different light on this, finding that only the biased group, that is, girls diagnosed after their first birthday had an increased tendency to complain about aches and pains compared to their sisters. This wasn’t true for girls diagnosed earlier or before birth (DIESC 2009). Spinal curvature A spinal curvature is probably more common among teenagers, especially hunching forwards (Otter 2009). This has not been confirmed in the Triple X syndrome group survey (Triple X syndrome group 2006). However, tall girls who are keen not to stand out are known to stoop to conceal their height. Constipation A triple X syndrome group survey found that constipation was relatively common, reported by 15/43 families with a daughter under 20 (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Dental problems Research into dental development in girls with triple X syndrome is sparse. A Unique study day found that 14/20 families said their daughter had some sort of dental problem. Problems described include poor enamel formation, pitting and need for fluoride coating (Unique). Urogenital tract Genitourinary and kidney malformations may be slightly more common in girls with triple X syndrome. It may make sense to scan the genitourinary tract with special attention prenatally (Tartaglia 2010; Otter 2009). However, the Triple X syndrome survey found no evidence of abnormalities in 43 girls diagnosed prenatally, although one had a membrane over the vagina, one was born with a single kidney and one was prone to urine infections (Triple X syndrome group 2006). Seizures and abnormal EEGs Some authors have suggested that in a minority of girls, unusual EEGs (electroencephalograms - recordings of the brainwave patterns from the tiny electrical signals from the brain) and seizures may be found. Treatment with anti-epileptic drugs was effective (Otter 2009; Tartaglia 2010). Brain imaging Two small follow-up studies of women from the 1960s newborn groups found that their brains were on average smaller than those of women without triple X syndrome. One of the studies also found focuses of white matter in the brains of around a quarter of girls and women with triple X syndrome. It’s unclear what this finding means (Tartaglia 2010). Heart problems Heart problems have been described, including holes between the upper or lower heart chambers (atrial or ventricular septal defects), pulmonic stenosis (the entrance to the 14 artery that takes blood to the lungs is unusually narrow) and aortic coarctation (the aorta that takes the blood from the heart to the rest of the body is narrowed (Tartaglia 2010). Screening and management of girls and women with Triple X syndrome There is no general agreement among doctors as to whether girls and women with triple X syndrome should have regular medical checks or not. Items in the schedule below were suggested by Dr Maarten Otter (Otter 2009) and by Dr Nicole Tartaglia. Talking about development and learning, Dr Tartaglia warns: ‘If present, developmental concerns and educational struggles should be addressed aggressively instead of taking a ‘wait and see’ approach, since they are unlikely to improve or ‘catch up’ without targeted interventions and delaying treatment will lead to poorer outcomes’ (Tartaglia 2010). Prenatal Focus on genitourinary tract while scanning Neonatal Normal paediatric screening PrePre-school EEG studies as indicated by medical history Heart evaluation Kidney ultrasound Comprehensive developmental evaluation: examination by developmental paediatrician or paediatric neurologist focusing on language, social and motor development Eye test Speech and language screening Investigation of learning needs Family and individual support at home and at school Primary school age Repeat EEG if abnormalities found on pre-school EEG Eye test Hearing test Social functioning test Multidisciplinary assessment to identify strengths and weaknesses and develop interventions and support Educational and learning needs assessment Family and individual support at home and at school Secondary school age Social functioning test Educational and learning needs assessment Family and individual support at home and at school School leavers Physical examination if symptoms arise Occupational investigation and support if necessary Adults Physical examination if symptoms arise Psychological / psychiatric examination if symptoms arise 15 Support and Information Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group, G1, The Stables, Station Road West, Oxted, Surrey RH8 9EE, United Kingdom Tel/Fax: +44(0)1883 723356 info@rarechromo.org I www.rarechromo.org Join Unique for family links, information and support. Unique is a charity without government funding, existing entirely on donations and grants. If you can, please make a donation via our website at www.rarechromo.org Please help us to help you! In the United Kingdom Triple X syndrome Family Network Support Group 32 Francemary Road London SE4 1JS +44 (0) 20 8690 9445 helenclements@hotmail.com In the US www.genetic.org In the Netherlands www.triple-x-syndroom.nl Unique lists external message boards and websites in order to be helpful to families looking for information and support. This does not imply that we endorse their content or have any responsibility for it. This information guide is not a substitute for personal medical advice. Families should consult a medically qualified clinician in all matters relating to genetic diagnosis, management and health. Information on genetic changes is a very fast-moving field and while the information in this guide is believed to be the best available at the time of publication, some facts may later change. Unique does its best to keep abreast of changing information and to review its published guides as needed. The guide was compiled by Unique and reviewed by Professor Maj Hultén, Professor of Reproductive Genetics, University of Warwick and by Dr Gaia Scerif, Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford 2009. PM. Updated 5/2011; 11/2013 v2 Copyright © Unique 2013 Rare Chromosome Disorder Support Group Charity Number 1110661 Registered in England and Wales Company Number 5460413 16