Part 2 - BishopAccountability.org

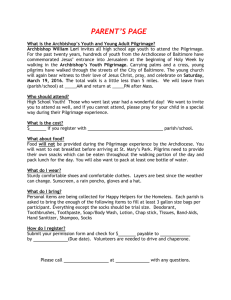

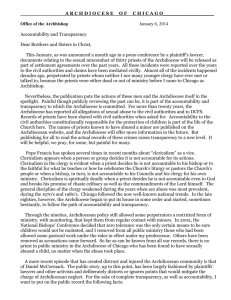

advertisement