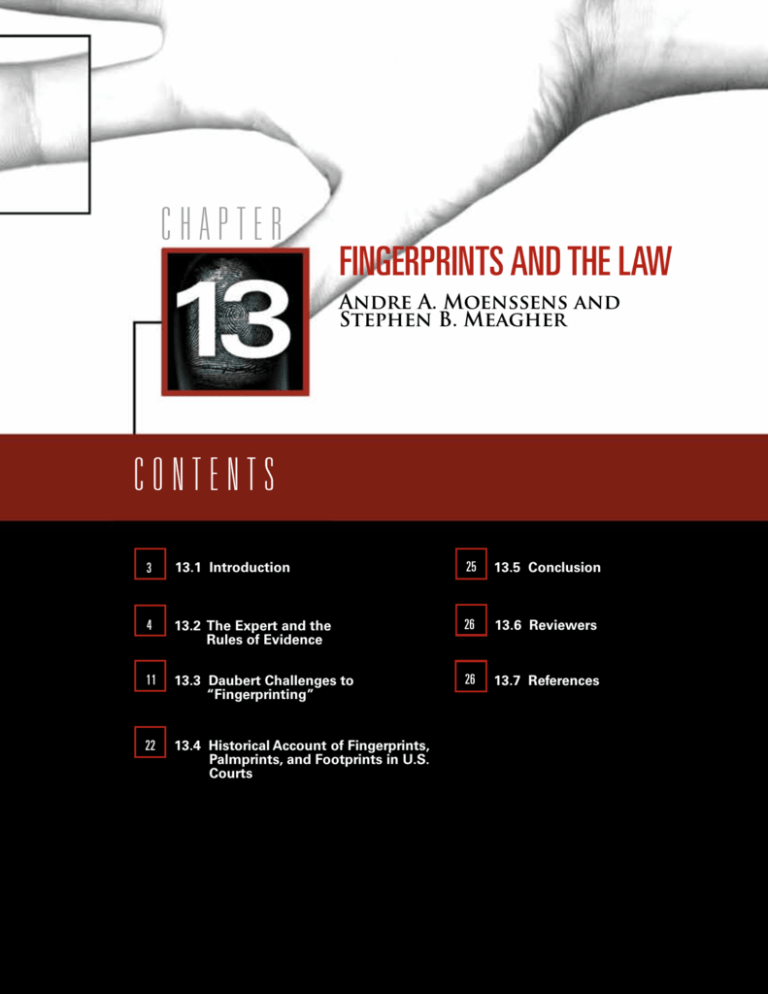

Fingerprint Sourcebook Chapter 13: Fingerprints and the Law

advertisement