Historical Development of Fingerprinting

advertisement

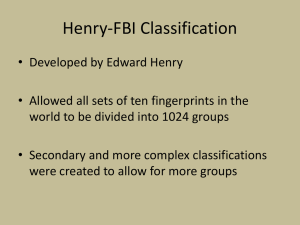

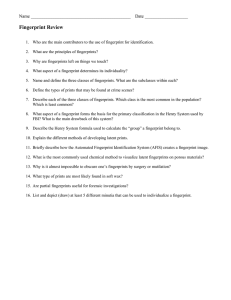

The historical development of fingerprinting The use of fingerprints, possibly as signatures, on ancient artefacts suggests that human beings were aware of friction ridge patterns thousands of years ago. The ancient Chinese, for example, used clay seals impressed with finger or thumb-marks to seal official documents, prior to the first century B.C. However, it was not until the late 17th century that the first written description of friction ridge patterns appeared. This took the form of an illustrated paper presented by Dr. Nehemiah Grew (16411712) to the Royal Society in London in 1684. At about the same time, the Italian professor Marcello Malpighi (1628-94) (after whom the Malpighian layers of the skin are named) published his work De Externo Tactus Organo (1686), which contained some information concerning the function of friction skin. Almost two centuries elapsed before the potential use of friction skin as a means of identifying an individual was recognised. In a communication to the scientific journal Nature on October 28, 1880, Dr. Henry Faulds (1843-1930), a medical missionary working in Japan, noted that: “When bloody finger-marks or impressions of clay, glass, &c., exist, they may lead to the scientific identification of criminals.” In his wide-ranging letter, Faulds proceeded to report two separate cases in which he was able to utilise finger-marks left at the crime scene (in one instance, sooty fingermarks on a white wall; in the other, greasy finger-marks on a glass) to assist the Japanese police with their criminal investigations. The appearance of his communication in Nature resulted in an almost immediate contribution to the journal from Sir William Herschel (1833-1917) (November 25, 1880). In this, he cited his own use of fingerprints for the signature of contracts (as a dependable method of individual identification) over the previous twenty years, whilst serving as a colonial administrator in India. Furthermore, he asserted that fingermarks remained unchanged over that period of time. These communications gave rise to considerable discussion over which of the two men should be recognised as the first to appreciate the uniqueness of fingerprints and the role they might play in the identification of individuals. The next person to play a key role in the historical development of fingerprinting was Sir Francis Galton (1822-1911). His comprehensive research into the subject in the late 19th century led to the publication of his classic book, Finger Prints, in 1892. In this, he was able to clearly illustrate two of the fundamental principles of fingerprints; namely that the pattern of an individual’s fingerprints was persistent over time and that no two fingerprints were exactly the same. He also initiated a method of classifying fingerprints, recognising three basic types of fingerprint pattern: whorls, loops and arches. Two years later, Sir Edward Richard Henry (1850-1931) (at that time Inspector General of Police in Bengal, India; later to become Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, 1903-1918) used Galton’s observations as a basis to develop his own fingerprint classification system. The Henry Classification System, as it became known, was completed in 1897 and officially adopted in India that same year. This replaced the previously used Bertillon system; a systematic procedure whereby a series of anthropometric (body) measurements were taken, together with a detailed description of the individual (the ‘portrait parlé’) and, more latterly, photographs. In 1901, following the recommendations of the Belper Commission, the Henry Classification System was adopted by the newly created Fingerprint Branch at Scotland Yard, and, with some modification, is still in use today in the majority of English-speaking countries. It is worth noting that most Spanish-speaking countries currently utilise a different fingerprint classification system, based on one that was independently devised in Argentina in 1891 by Dr. Juan Vucetich (1858-1925).