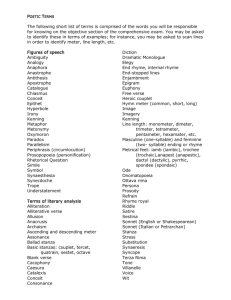

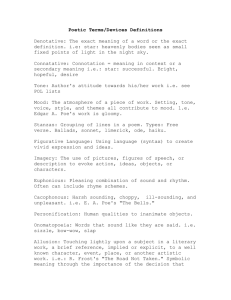

Introduction to Literature_2

advertisement

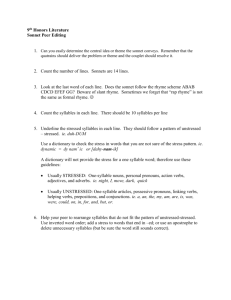

WEEK 4 – INTRO. TO LIT. LECTURE NOTES ELEMENTS OF POETRY CONT’D – RHYME, RHYTHM & METRE RHYME & RHYME SCHEMES: Rhyme is the repetition of identical vowel sounds in the stressed syllables of two or more words, as well as of all subsequent sounds after this vowel sound. The purpose of rhyme in a poem can be to establish or intensify the rhythm; and/or to establish the unities and divisions within a poem. A poet’s rhyme scheme (pattern of rhymes) may distinguish the stanzas from each other, as well as unify the poem as a whole through its recurrent regularity. The two or more words that rhyme become linked and the lines in which they appear become a separate unit. In the heroic couplet, for instance, the rhyme sets the verse into two-line pieces and makes each pair suggest or become a distinct and complete statement: Some have for wits, then poets passed, a Turned critics next, and then proved plain fools at last. a Some neither for wits nor critics pass, b As heavy mules are neither horse nor ass. b (Alexander Pope, 1711) History of rhyme: Research seems to suggest that rhyme as we know it originated in the Catholic Church in Africa during the reign of the Roman Emperor Tertullian (160-230 A.D.) Later, European priests began introducing rhymes into services to help make long passages of liturgy easier to remember and listen to. By the 4th century A.D. important liturgies had evolved into rhymed poems. During the Middle Ages (around 5th Century A.D. to 15th century), hymns were composed that combined alliteration and end-rhyme. Unrhymed verse written in English dates as far back as the 16th century. At this time blank verse first appeared when the Earl of Surrey used it for his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid (1540). Over the years, blank verse has become the most common English verse form, especially for extended poems, as it is considered the closest form to natural patterns of English speech. Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and especially John Milton (Paradise Lost 1667) made ample use of this type of verse and are generally credited with establishing blank verse as the preferred English verse form. The modern trend has been toward dispensing with rhyme, or minimizing its use. While the use of the imperfect rhyme has increased, nonrhyming forms have become even more popular; free verse and other unrhymed verse have become the dominant means of poetic expression. Types of rhymes: Perfect rhyme (true/full rhyme) – an exact match of sounds in a rhyme; only the sounds before the first stressed vowel in the rhyming words may differ. Eg. bard/lard/marred/guard. Imperfect rhyme (slant/oblique/off/half rhyme) – the sounds are similar but not exactly the same; consonant and vowel sounds are similar but not “perfectly” the same. Eg. port/heart, bard/ beard/ board. Many modern poets deliberately use imperfect or “partial” rhymes in which the reader experiences the pleasure of the expected but varied sound, which is also often used to contribute to or enhance the meaning of the imperfectly rhymed words. Masculine rhyme – consists of a single stressed syllable. Eg. far/car, still/hill. Feminine rhyme – has either two (double rhyme) or three (triple rhyme) syllables. It involves one stressed syllable followed by one or two identical sounding unstressed syllables. Eg. shatter/splatter (double), clattering/flattering. Double and triple rhymes usually have a comic effect, for example, in Byron’s Don Juan, he addresses the husbands of educated wives: But – Oh! Ye lords of ladies intellectual 1 Inform us truly, have they not hen-pecked you all? End rhyme occurs at the end of a line of verse. It is the most frequent type of rhyme. Beginning rhyme occurs at the beginning of a line of verse. Internal rhyme is between two or more words within a single line of verse. Eg. “And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil.” Eye rhyme – the words appear to rhyme only based on their spelling; they sound completely different when pronounced. Eg. dough/tough, bread/bead, prove/love, daughter/laughter. RHYME SCHEME: the pattern of rhyme in a poem. A lower case letter is assigned to each new rhyming sound. Certain rhyme schemes follow specific conventions: Couplet – two successive rhymed lines which are equal in length. A heroic couplet is a pair of rhyming lines in iambic pentameter. In Shakespeare’s plays, characters often speak a heroic couplet before exiting the stage. Eg. Hamlet’s couplet at the end of the scene in which he discovers that his uncle has killed his father the king: The time is out of joint: O cursed spite, a That ever I was born to set it right! a Some couplets stand alone, as in the typical epigram (a short poem, often comic, that ends with a sharp turn of wit or meaning), and in two-line stanzas. When placed at the end of a poem or scene in a play, as in the English/Shakespearean sonnet, the couplet tends to form a complete thought, with the statement’s meaning extending or contrasting the structure and contents of the preceding lines. When couplets appear as the basic verse form of longer poems, they function as complete units as well as steps in a narrative or lyric flow. In the Neoclassical Period the heroic couplet was the most popular verse used in translations of The Aeneid and The Iliad. However, during the 18th century the heroic couplet declined, and by the Romantic Period it was seen as artificial and mechanical. The heroic couplet is still not in frequent use today. Quatrain – a four line stanza. It is the most common form of English verse and has many variants. No rhyme needs to exist in a quatrain, but there are a few common rhyme schemes used by poets, like abba. One of the most important is the heroic quatrain, written in iambic pentameter with an abab rhyme scheme. The ballad stanza is the most common pattern of the ballad form which consists of 4 lines rhymed abcb or abab, in which the 1st and 3rd lines have 4 metrical feet and the 2nd and 4th lines have 3 feet. Eg. Ah! Well-a-day! What evil looks a Had I from old and young! b Instead of the cross, the Albatross c About my neck was hung. b (Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1798) The ballad stanza is also called common metre, and it has a heavy pause after the second line. “Amazing Grace” and many other hymns are in common metre, and they influenced many poets who followed the hymnal tradition, such as George Herbert and Emily Dickenson. Sonnet – a single stanza lyric poem (poem focusing on the speaker’s feelings) containing 14 lines written in iambic pentameter. It was introduced to English in the 16th century and flourished during the Renaissance Period, specifically the Elizabethan Period, when major writers composed many sonnets to their lovers. It declined during the Neoclassical Period, but the Romantic poets revived the form and it continues to be used occasionally even by modern poets. William Shakespeare is the best known author of sonnets in English. 19th century sonneteers include John Keats and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Sonnets may address a range of themes, but love, the original subject of the sonnet, seems to continue to be the most prevalent. Italian/Petrarchan sonnet – developed by the Italian poet Petrarch, it is divided into an octave (first 8 lines) with the rhyme scheme abbaabba or abbacddc, and a sestet (final 6 lines) with the rhyme scheme cdecde or cdccdc. The sestet normally marks a shift in mood or focus. Shakespearean/English/Elizabethan sonnet – was made famous by Shakespeare. It contains three quatrains (four lines of verse) and a final couplet. The rhyme scheme is ababcdcdefefgg. In this sonnet the 2 shift in focus/mood comes after the 12th line. Shakespeare usually uses his couplet at the end to sum up the content of the preceding lines with a general comment, a motto, or a promise. Spenserian sonnet – is a variant of the Shakespearean sonnet developed by the poet Edmund Spenser. It has the rhyme scheme ababbcbccdcdee. Once again the shift in focus comes after line 12. Tercet – a grouping of three lines, often but not always bearing a single rhyme. It can refer to a part of a larger stanza like the two three line components of a sestet in the Italian/Petrarchan sonnet, or be a stanza in itself, like the terza rima stanza. The terza rima is a system of tercets with an interlocking rhyme scheme: aba bcb cdc etc. Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind” (1820) is perhaps the most famous English example, and Robert Frost used it in 1928 for “Acquainted with the Night”: I have been one acquainted with the night. I have walked out in the rain – and back in rain. I have outwalked the furthest city light. a b a I have looked down the saddest city lane, I have passed by the watchman on his beat And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. b c b RHYTHM & METRE Rhythm and metre are the building blocks of poetry. Rhythm is the pattern of sound created by the varying length and emphasis given to different syllables. The beat or pattern is established by pauses and stressed and unstressed syllables. A fixed and recurring rhythm establishes the metre; when stresses fall systematically and at regular intervals, the result is metre. The many metres that are used in poetry are classified by differences in those intervals. The pace of the rhythm and the strength of the beat help determine the tone (writer’s attitude towards the subject) of the work, and the rise and fall of spoken language is called its cadence. Metre helps to speed up the reading of a poem or slow it down; it sets rhythmic patterns that structure the content and establish the tone. There is a close connection between a poem’s subject matter and metre; serious themes call for certain metres and comic approaches call for others. The metrical unit of a line of verse is called a foot and usually consists of one stressed syllable and one or more unstressed syllables. Standard English feet include the iamb, trochee, anapest, dactyl, spondee and pyrrhic: iamb – an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable – today trochee – stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable – carry anapest – 2 unstressed syllables followed by stressed syllable – it is time dactyl – a stressed syllable followed by 2 unstressed syllables – difficult spondee – 2 successive syllables with strong stresses – stop, thief! pyrrhic – 2 successive syllables with light stresses – up to no good ACTIVITY: Read the following lines aloud and listen to the specific type of feet used in each line. Iambic – Anapestic – Trochaic – Dactylic – Spondaic – Pyrrhic – The curfew tolls the knell of parting day. The Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold. There they are, my fifty men and women. Eve with her basket, was Deep in the bells and grass. Good strong thick stupefying incense smoke. (the first 2 feet of the line) My way is to begin with the beginning. (the 2nd and 4th feet have 2 lightly stressed syllables) 3 Most English poetry has four or five feet in a line, but there can be as few as one or as many as eight, though these are rare: Monometer – one foot Dimeter – two feet Trimeter – three feet Tetrameter – four feet Pentameter – five feet Hexameter – six feet Heptameter – seven feet Octameter – eight feet ACTIVITY: See if you can identify the type of metric line used in the above examples. Few poems are written using only one type of foot; poets generally vary the metrical pattern to keep their poetry from sounding too singsongy or restricted. Identifying the poem’s metre requires identifying the dominant type of foot used. Common metrical lines include iambic pentameter, used in blank verse, and trochaic tetrameter. The ballad form uses alternating tetrameter and trimeter, usually iambic and rhyming. The villanelle is a 19-line poem made up of five tercets and a final quatrain in which all 19 carry one of only two rhymes. The metre of the villanelle does not have to conform to any particular type, and can use more that one metrical pattern in the poem. Free verse does not conform to any fixed metre or rhyme scheme. It has no or very few units of recurrent stress patterns. Examples: Iambic tetrameter alternating with iambic trimester (used in the ballad stanza/common metre) A slumber did my spirit seal; I had no human fears: She seemed a thing that could not feel The touch of earthly years. Iambic pentameter (used in the heroic quatrain) – I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind, And did He stoop to quibble could tell why The little buried mole continues blind, Why flesh that mirrors Him must someday die…. 4