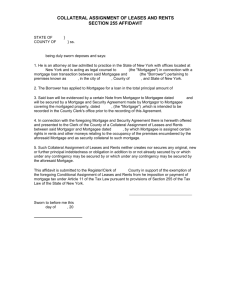

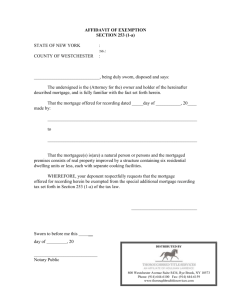

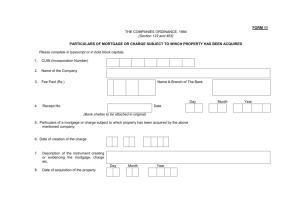

mortgages, fixtures, fittings, and security over personal property

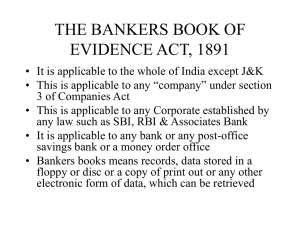

advertisement