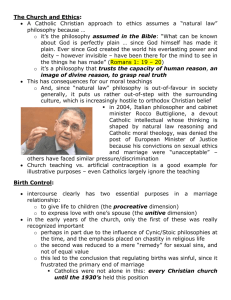

CHRISTIAN PHILOSOPHY OF MAN Outline

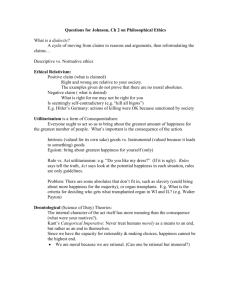

advertisement