Environmental Management- Revising the Marketing Perspective

advertisement

Carl P. ZeithamI & Valarie A. ZeithamI

Environmental

Management:

Revising the

Marketing

Perspective

D

EBATE continues in the marketing literature

concerning the substance and scope of marketing

(Anderson 1982, Amdt 1978, Bartels 1974, Hunt

1976b, Shruptine and Osmanski 1975, Webster 1981,

Wind and Robertson 1983). The debate involves several overlapping topics: (1) theoretical descriptions of

the marketing process (Bagozzi 1974, 1975; Kotler

1972); (2) integrative paradigms designed to stimulate

conceptual and empirical development (Bartels 1970,

1974; Hunt 1976a, 1976b); and (3) prescriptive works

concerned with extending the traditional boundaries

of marketing (Kotler and Levy 1969, Lazer 1969, Luck

1969, Stidsen and Schutte 1972, Wind and Robertson

1983). Despite the controversy prevalent in these theoretical works, two generally accepted conclusions

emerge from a review of the literature:

• Marketing involves facilitating the exchange relationship that exists between an organization

and its external environment; and

Carl P. ZeithamI is an Assistant Professor of Management, and Valarie

A. Zeithaml is an Assistant Professor of Marketing, Texas A&M University, This article has benefited from discussions with Frank Paine and

William Cron, and from comments by three anonymous reviewers,

46 / Journal of Marketing, Spring 1984

Environmental management argues that marke

ing strategies can be implemented to change th

context in which the organization operates, bot

in terms of constraints on the marketing functio

and limits on the organization as a whole. Th

current movement toward innovative, entrepre

neurial management—a return to the roots c

American enterprise—captures the essence of thi

perspective. The absence or, at a minimum, th

understatement of this perspective within thi

marketing literature limits the contribution of mar

keting to the management of organization-envi

ronment relationships. The paper reviews thede

velopment of environmental management in allie

disciplines, offers a typology of strategies, dis

cusses implementation issues, and presents im

plications of the perspective for marketing theory

• Marketing principles and processes are applicable to exchanges beyond those involving the

products and services of profit-oriented businesses.

Marketing's concern with the organization-envi

ronment exchange process and the broadening of thi

marketing concept have emphasized the importance o

the external environment for marketing theorists ant

managers. However, an examination of the literaturf

suggests that the traditional marketing perspeclivt

concerning this relationship is restricted. As a con

sequence, the overall contribution that marketing car

make to the management of organization-environmen

relationships is limited. Consistent with this review

a third conclusion is proposed:

• Marketing theory adopts an essentially

stance with respect to the external environment

Although many successful marketers employ

proactive, entrepreneurial philosophy in practice, I»

marketing discipline appears to be reluctant to assuiw

a similar posture. The marketing management Iitef^

ture provides support for this observation. The

widely used conceptual model of the scope of

keting, McCarthy's "4 Ps" model, views marketm!

as three concentric circles (McCarthy I960). Aroun

Journal of Marketing

Vol. 48 {Spring 1984).

the inner circle (the consumer) are the "controllable

factors" of price, place, promotion, and product, and

the "uncontrollable factors" of political and legal environment, economic environment, cultural and social

environmental, resources, etc. As conceptualized by

McCarthy, the internal aspects of the organization can

be managed, but the external environment is established and must be accepted as is. Writers such as

Holloway and Hancock (1973) and Scott and Marks

(1968) pioneered an environmental approach to marketing in the 1960s; the approach was only environmental in the sense that it emphasized that the environment (e.g,, consumers, culture, legal framework,

technology, and institutions) constrained marketing

activities. Furthermore, the marketing concept embodies the essence of this traditional view of the organization-environment relationship:

The marketing concept is a management orientation

that holds the key to achieving organizational goals

[and] consists of the organization determining the needs

and wants of target markets and adapting itself to delivering the desired satisfactions more effectively and

efficiently than its competitors (Kotler 1980, p. 22).

The organization first attempts to discover what the

consumer wants, then structures organizational goals,

objectives, and activities to deliver the desired product, service, or idea better than competing organizations. The domain of marketing activity appears to start

at a point where a system of environmental constraints

already has been defined for the organization. These

constraints range from established wants and needs of

consumers to a variety of competitive, legal, technological, and social factors. Only in peripheral work,

such as the development of social marketing (Kotler

and Zaltman 1971), have marketers explicitly acknowledged the relevance and feasibility of less deterministic approaches to marketing. In general, marketing theory appears to assume that the organization

confronts predetermined opportunities in the environment. Marketing strategies, therefore, are viewed as

a set of adaptive responses.'

The reactive perspective is reflected in the typical

marketing manager's reliance on marketing intelli-

everal early marketing theorists acknowledge the proactive aspects

marketing^ Fox example, Paul Mazur (1953) pointed to marketing's

m siimulating demand, and later portrayed marketing as "the de, ^^'^"^^'"'l^f I'ving" (Mazur 1958). Similarly, Harry Hansen

) revealed a proactive emphasis in his definition of marketing:

Marketing is the process of discovering and translating consumer needs and wants into products and service specifia'lons. creating demand for these products and services,

""a men, m turn, expanding this demand (p.4).

authors did

ent theory development and practice by marketers.

gence, forecasting, and market research. Marketing

intelligence is gathered to identify technological innovations, appraise current performance, monitor

competitors, assess political and regulatory developments, evaluate societal changes, and predict the economic impact of these and other environmental developments on organizational goals and performance.

In other words, the marketing manager attempts to

analyze the forces operating in the environment and

implements organizational or strategic changes to adapt

to environmental demands. Similarly, forecasting

market demand trends and analyzing supply and price

conditions illustrate activities designed to anticipate

future environmental states so that production levels

and other company-controlled variables can be adjusted to optimize the fit between the environment and

the organization. In a sense, market research functions as a technique to adapt the organization to one

critical aspect of its environment, the consumer. These

marketing activities generally provide the starting point

for marketing efforts, thereby perpetuating the reactive perspective in practice. As Webster (1981) found

in a survey of top managers' views of the marketing

function, marketing managers were perceived as "not

sufficiently innovative and entrepreneurial in their

thinking and decision making" (p. 11),

While effective marketers often implement strategies designed to alter the conditions under which they

operate (see the examples contained in Table 1), this

paper holds that marketing theory should explicitly

adopt a proactive, entrepreneurial orientation to the

management of the external environment. The perspective developed in this paper, referred to as environmental management, argues that marketing stt^tegies can be implernented to change the context in

which the organization operates, both in terms of constraints on the marketing function and limits on the

organization as a whole. The current movement toward innovative, entrepreneurial management—a return to the roots of American enterprise—captures the

essence of this perspective. The absence or understatement of this perspective within the marketing literature limits the contribution of marketing to the

management of organization-environment relationships. The purpose of this paper is to supplement existing marketing theory by emphasizing that marketing is a significant force which the organization can

call upon to create change and extend its influence

over the environment.

The paper is divided into four sections. First, the

development of the environmental management perspective in allied disciplines is reviewed. Second, a

typology of environmental management strategies is

suggested with examples. Third, implementation issues that may influence the selection and application

of environmental management strategies are identi-

Environmental Management / 4 7

fied. Finally, implications of the environmental management perspective for marketing theory are discussed.

Background and

Reconceptualization of the

Organization-Environment

Relationship

By the late 1970s management theorists generally

adopted the open systems perspective of organizations

and agreed on the centra! importance of the external

environment for management (Anderson and Paine

1975, Bamard 1938, DilJ 1958, Emery and Trist 1965,

Katz and Kahn 1966, Terreberry 1968, Thompson

1967). Traditional organization theory tended to view

the environment as a deterministic influence to which

organizations adapt their strategies, structures, and

processes. This attitude was reflected particularly in

landmark empirical research such as Bums and Stalker

(1961), Duncan (1972), Lawrence and Lorsch (1967),

and Neghandi and Reimann (1973). Environmental

attributes such as turbulence, hostility, diversity,

technical complexity, and restrictiveness (Khandwalla

1977) were thought to determine both organizational

and performance variables. In summary, the traditional environmental determinism perspective conceptualized the environment as a causal variable: Organizational performance was dependent upon the efficient

and effective adaptation of organizational characteristics to environmental contingencies.

In contrast, recent theory and research in management and the social sciences has reconceptualized the

relationship between the organization and the external

environment (Aldrich 1979; Bourgeois 1980; Child

1972; Galbraith 1977; Kotter 1979; Miles and Snow

1978; Pfeffer 1978; Pfeffer and Salancik 1978; Porter

1979, 1980). Based on observations, research, and

extensions of the traditions found in the business policy and corporate social responsibility literatures, these

authors challenge the position that organizations are

or need to be passive-re active entities with respect to

the external environment. Instead, they argue that organizations can and do implement a variety of strategies designed to modify existing environmental conditions. Although these writings acknowledge the

impact of broad internal and external contingencies,

they maintain that organizations can become proactive

agents of change by attempting to manage their external environments.

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to review in detail all of the works listed above, several

key approaches found in this literature may facilitate

an understanding of the perspective. One major portion of the literature has focused on the resource dependence model. This theoretical approach, devel-

AO

I

IAI....AI

«<

oped by Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) and summarized

by Kotter (1979), argues that organizations have vaiying degrees of dependence on external entities, particularly for the resources they require to operate. In

many instances, the external control of these resources may reduce managerial discretion, interfere

with the achievement of organizational goals, and ultimately threaten the existence of the focal organization. Confronted with a costly situation of this nature,

management actively directs the organization to manage or alter the external dependence. Strategies suggested to achieve a reduction in dependence include

the prudent selection of operating domains (e.g., industries with limited competition and regulation coupled with ample suppliers and customers), merger, cooptation, coalition formation, contractual relationships, advertising and public relations efforts, activities designed to reduce competition, political strategies implemented to influence regulation, and structural

changes. The intent in each case is to develop countervailing power with respect to the external environment.

A second approach using this perspective is found

in the area of business policy or strategic management. The reconceptualization of the organization-environment relationship is less evident, however, since

a proactive, opportunistic management stance has been

emphasized traditionally in business poHcy theory and

research (Bourgeois 1980; Child 1972; Hatten, Schendel, and Cooper 1978; and Mintzbcrg 1972). Twoexamples from this literature are the works of Miles and

Snow (1978) and Porter (1979, 1980). Miles and Snow

develop an organizational typology based on strategic

choices concerning key managerial problems. One of

their organization types, prospectors, clearly typifies

the proactive orientation of many organizations. Based

on their research, prospectors "are the creators of

change and uncertainty to which competitors must respond" (1978, p. 29).

Porter (1979) identifies several external forces with

which strategic decision makers must contend in their

industries, including the threat of new entrants, tne

bargaining power of buyers and suppliers, the threat

of substitute products and services, and the degree of

rivalry among existing competitors. To manage these

environmental forces he suggests strategies such as the

development of barriers to entry (e.g., product differentiation, promoting favorable government policy)^

raising switching costs to buyers, eliminating switching costs with respect to suppliers, vertical integration, and focusing attention on high growth marfe'

segments. Porter also links these strategies to the evolutionary stages of industry development, h i i h t " ?

the usefulness of this construct.

A third approach, which serves to integrate n

of the literature discussed above, was developed

[iaily as an alternative to the environmental determinism perspective. Two authors representative of this

approach are Pfeffer (1978, chapter 6) and Galbraith

(1977, chapter 14). In each case, these authors develop specific sets of strategies to manage the external

environment and discuss the conditions under which

they are appropriate. Consistent with previous references, Pfeffer argues: "Rather than designing the organization to 'fit' the environment (the position of the

contingency theorists), it is more likely that first the

organization will attempt to design its environment to

fit its present structural arrangements" (1978, pp. 141142). He then outlines methods that can accomplish

this task: managing competition, promoting regulation

to reduce competition, managing symbiotic interdependence, and managing uncertainty, organizational

legitimation, and political action.

Galbraith discusses similar strategies in greater detail under a concept which he termed "environmental

management." He partitions environmental management strategies into three categories: independent

strategies, cooperative strategies, and strategic maneuvering. Independent strategies are means by which

the organization can reduce environmental uncertainty

and dependence by "drawing in its own resources and

ingenuity" (1977, p. 204). Cooperative strategies involve implicit or explicit cooperation with other elements in the environment. Strategic maneuvering includes strategies designed to change or alter the task

environment of the organization. To expedite the discussion, the remainder of this paper employs environmental management to denote the proactive perspective on organization-environment relations.

A Typology of Environmental

Management Strategies

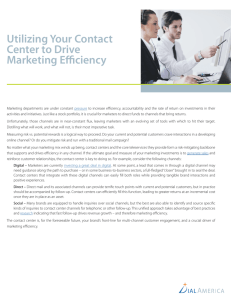

Table 1 outlines and defines broad categories of environmental management strategies using Galbraith's

three-part framework, and provides examples of specific strategies within each category. As appropriate.

It has been modified or supplemented with strategies

discussed by other authors. Table 1 neither proposes

new strategies nor constructs an exhaustive list of all

possible strategic options; rather, the typology is intended to develop a strategic perspective through which

niarketmg theory can develop the more entrepreneurial proactive orientation described above. Under appropriate conditions, many of the strategies may be

used together in an integrated program of environn^ental management.

Nine independent environmental management

ategies are contained in Table 1. These strategies

l^ 'Implemented regularly by individual firms in an

^ empt to modify their competitive environments. One

ent example of competitive aggression, which typ-

ically involves activities designed to differentiate the

firm or its products, is the use of videotapes by the

record industry. These promotional tapes played on

cable television (e.g., MTV) and in nightclubs have

revived a slumping industry and dramatically altered

the competitive environment. Kellogg's advertising

campaign promoting the cereal industry (competitive

pacification), Weyerhauser's reforesting advertising

campaign (public relations), Heinz's suit against

Campbell Soup (legal action), and Arco's corporate

constituency program with shareholders (political action) are other specific examples of independent strategies.

In some situations two or more organizations may

implement cooperative environmental management

strategies. The naming of Douglas Fraser of the UAW

to the Chrysler board (co-optation) and the political

initiatives of industry associations and other special

interest groups (coalition) are recent examples of these

collective efforts. Cooperative strategies are selected

by many firms on the assumption that combined action reduces risks and costs to individual organizations while increasing their power.

The third category of environmental management

strategies included in Table 1 is termed strategic maneuvering. These strategies represent conscious efforts by an organization to change the task environment in which it operates. In a recent article, Zoltners

and Dodson (1983) discuss a form of strategic maneuvering which involves proactively seeking segments of buyers who possess the least power to Influence the organization adversely. As an additional

example, the availability of products such as pocket

calculators, feminine hygiene deodorants, and personal computers radically altered the environments of

organizations which offered them.

As the typology is reviewed, it is important to note

that many of the strategies are strictly within the marketer's domain, while others have been supported by

marketing activities. Marketing theory, however, has

tended to view them as tactical reactions to existing

conditions rather than as strategic actions designed to

modify organizational contexts. For example, competitive aggression includes pricing, product distribution, and promotion. Voluntary action is essentially

synonymous with "social responsibility marketing."

Smoothing is consistent with "synchromarketing."

Political action (e.g., through corporate constituency

programs or grass roots lobbying) involves the marketing of ideas to employees, shareholders, community leaders, and politicians to influence the regulatory context of the organization.

Although all of these strategies can be classified

as environmental management strategies, certain factors may influence their selection and implementation. The following section offers some guidance con-

Environmental Management / 4 9

TABLE 1

A Framework of Environmentai Management Strategies

Environmental

Management

Strategy

Examples

Definition

Independent Strategies

Competitive

aggression

Competitive

pacification

Public relations

Voluntary action

Dependence

development

<

Legal action

Political action

Smoothing

Demarketing

Implicit

cooperation

Contracting

Co-optation

<

Coalition

Domain

selection

Diversification

Focal organization exploits a distinctive

competence or improves internal efficiency

of resources for competitive advantage.

Independent action to improve relations with

competitors.

Product differentiation.

Aggressive pricing.

Comparative advertising.

Helping competitors find raw materials.

Advertising campaigns which promote entire

industry.

Price umbrellas.

Establishing and maintaining favorable

images in the minds of those making up

the environment.

Voluntary management of and commitment to

various interest groups, causes, and social

problems.

Creating or modifying relationships such that

external groups become dependent on the

focal organization.

Corporate advertising campaigns.

Company engages in private legal battle with

competitor on antitrust, deceptive

advertising, or other grounds.

Efforts to influence elected representatives to

create a more favorable business

environment or limit competition.

Attempting to resolve irregular demand.

Attempts to discourage customers in general

or a certain class of customers in particular,

on either a temporary or a permanent

basis.

McGraw-Hill's efforts to prevent sexist

stereotypes.

3M's energy conservation program.

Raising switching costs for suppliers.

Production of critical defense-related

commodities.

Providing vital information to regulators.

Private antitrust suits brought against

competitors.

Corporate constituency programs.

Issue advertising.

Direct lobbying.

Telephone company's lower weekend rates.

Inexpensive airline fares on off-peak times.

Shorter bours of operation by gasoline

service stations.

Cooperative Strategies

Patterned, predictable, and coordinated

Price leadership.

behaviors.

Negotiation of an agreement between the

Contractual vertical and horizontal marketing

organization and another group to exchange

systems.

goods, services, information, patents, etc.

Process of absorbing new elements into the

Consumer representatives, women, and

leadership or pollcymaking structure of an

bankers on boards of directors.

organization as a means of averting threats

to its stability or existence,

Two or more groups coalesce and act jointly

Industry association.

with respect to some set of issues for some Political initiatives of the Business RoundtaWe

period of time.

and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Strategic Maneuvering

Entering industries or markets with limited

IBM's entry into the personal computer

competition or regulation coupled with

market.

ample suppliers and customers; entering

Miller Brewing Company's entry into the

high growth markets.

beer market.

Investing in different types of businesses,

Marriott's investment in different forms of

manufacturing different types of products,

restaurants.

vertical integration, or geographic

General Electric's wide product mix.

expansion to reduce dependence on single

product, service, market, or technology.

50 / Journal of Marketing, Spring 1984

TABLE 1 (continued)

A Framework of Environmental Management Strategies

Environmental

Management

Strategy

Merger &

acquisition

Definition

Examples

Combining two or more firms into a single

enterprise; gaining possession of an

ongoing enterprise.

^_^^__^^_

ceming the conditions under which particular strategies

may be most beneficial.

Environmental Management

Strategies: Selection and

Implementation Issues

Once the environmental management perspective is

adopted by a marketer, consideration must then be given

to selection and implementation of appropriate strategies. Some strategies are obvious choices based on

their ability to focus on a particular component of the

external environment. For example, competitive

aggression may be selected to deal with the competitive/market envirormient, while political action would

be chosen in situations where the external political environment is the focus. Beyond this simple matching

of strategies to components of the environment, two

other considerations may be helpful during the strategy selection and implementation process. First, the

costs and benefits associated with the implementation

of alternative strategies should be evaluated. Second,

contingency approaches emphasized by theory and research in strategic management may provide guidance

in the selection and implementation of strategies.

The selection of an environmental management

strategy may depend on an analysis of costs versus

benefits captured in the return on investment calculations commonly used by strategic decision makers.

As marketers become involved more explicitly in

managing the external environment, they may assume

a major role in evaluating the financial consequences

of strategy decisions. Since marketers have traditionally been isolated from such concerns (Webster 1981,

wmd and Robertson 1983), familiarization with the

joncept of return on investment may be necessary.

"iplicit in the return on investment calculation are estates of the probability that a particular environmental management strategy will result in a more faorable environment for the firm. The calculation must

"Corporate the traditional, short-term financial view

f "^ ^"^ ^osts as well as the long-term impact

ind and Robertson 1983 for a discussion of this

)• Clearly, the marketer's expertise with adver-

Merger between Pan American and National

Airlines.

Phillip Morris's acquisition of Miller Beer.

tising, promotion, pricing, and market segmentation

strategies could be a valuable contribution to the evaluation of potential effectiveness.

Broad environmental contingencies also may influence the feasibility and timing of strategy implementation. The selective application of these strategies under certain conditions, called contingencies by

strategic decision makers, should enhance the performance and overall effectiveness of the organization.

Research focusing on the relationships between contingencies, environmental management strategies, and

performance should prove useful to marketing strategists. Two contingencies are proposed for purposes

of illustration: stage of the product/market/issue life

cycle and relative competitive position. Although other

contingencies are relevant, these factors should serve

to illustrate the value of incorporating contingency

factors in the strategy selection process.

The product life cycle has been a widely used construct in both the strategic management and marketing

literatures {Catry and Chevalier 1974, Fox 1973, Hofer

1975, Levitt 1965, Rink and Swan 1979, Wasson

1974). Recent empirical research employing the PIMS

data base has supported stage of the product life cycle

as a key strategic contingency variable (Anderson and

Zeithaml 1984). Relative competitive position (or

market share) also has received considerable theoretical and empirical attention, emphasizing in particular

its relationship to profitability (Buzzell, Gale, and

Sultan 1975; Hatten 1974; Patton 1976; Rumelt and

Wensley 1981; and Schoeffler, Buzzell, and Heany

1974). Several analytical tools have combined portions of the product life cycle with various levels of

market share to create aids to strategy formulation.

One such aid is the Boston Consulting Group's matrix. Once again, recent empirical research using the

PIMS data base has demonstrated the usefulness of

the BCG matrix for strategy formulation (Hambrick,

MacMillan, and Day 1982; MacMillan, Hambrick, and

Day 1982).

While it is beyond the scope of this paper to link

all of the environmental management strategies to particular stages and competitive positions, cooperative

strategies would seem to be appropriate for firms in

Environmental Management / 51

a mature stage of the product life cycle that also hold

a strong competitive position. Such strategies would

diminish the dysfunctional competitive rivalry among

entrenched competitors, thereby promoting higher

profitability within the industry. Second, the selection

of a specific competitive aggression strategy may be

dependent on stage of the product life cyc'e and competitive position. The return associated with product

differentiation may be greatest for a firm in a mature

market with a moderate to strong competitive position. Conversely, comparative advertising may benefit businesses in a weaker position during the growth

or shake-out stages. As a final illustration, social and

political issues may experience a life cycle similar to

products. Assuming such a phenomenon, the educational portion of a corporate constituency program may

be appropriate during earlier stages of the issue life

cycle, while grass roots and direct lobbying efforts

become necessary as the issue matures and legislative

action is imminent.

Our purpose in citing these examples is to suggest

^ approach which marketers and general managers

can use to operationalize the perspective discussed in

this paper. Substantial conceptual development and

empirical testing is required to yield a comprehensive

contingency approach for the application of the environmental management strategies listed earlier.

The Environmental Management

Perspective: Implications for

Marketing Theory

Discussion of the environmental management perspective by marketers may rekindle the controversy

over the broadening of the marketing concept. Critics

of the broadened view have argued that such efforts

tum the attention of marketers from existing problems, increase the level of abstraction in the marketing literature, and impede marketing scholars from

engaging in clear thinking about their own discipline

(Bartels 1970, 1974; Luck 1969). It is our view, how-

ever, that the environmental management perspective

allows marketers and marketing scholars to assume a

vantage point that minimizes these disadvantages. The

perspective encourages marketers to approach the issues facing their organizations with an increased level

of practicality and potential impact. It could also provide marketing scholars with a conceptual framework

that enables them to direct marketing toward a more

comprehensive partnership in the management of organization-environment relationships.

Environmental management fits comfortably into

much of the marketing theory literature. The perspective is consistent with theoretical schema developed

by Hunt (1976a). The strategies outlined in this paper

fit into all eight cells of the schema (i.e., combination

of the profit sector/nonprofit sector, micro/macro,

positive/normative categorical dichotomies). Environmental management strategies can be used by profit

sector firms as well as nonprofit sector firms. For example, coalitions, political action, and public relations strategies are appropriate in achieving the objectives of many nonprofit firms. The environmental

management perspective can fit into the micro cell when

used by individual organizations and the macro cell

when cooperative strategies involving marketing systems or groups of firms are implemented. The positive

and normative dimensions would also be represented;

the normative approach is illustrated by the prescriptions concerning selection and implementation made

in the previous section of this paper.

Marketing is a significant force which the organization can call upon to create change and extend its

influence over the environment. The environmental

management perspective is an initial step in this direction, one that may encourage marketers to assume

a more integral role in corporate strategy. As emphasized by Wind and Robertson (1983), "the strategy

perspective holds the promise of enriching, expanding, and increasing the relevance of the [marketing]

field" (p. 13).

REFERENCES

Aldrich, H. (1979), Organizations and Environments, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Anderson, Carl R. and Frank T, Paine (1975), "Managerial

Perceptions and Strategic Behavior," Academy of Management Journal. 18 (December), 811-823.

and Carl P, Zeithaml (1984), "Stage of the Product

Life Cycle, Business Strategy, and Business Performance,"

Academy of Management Journal, in press.

Anderson, Paul F. (1982), "Marketing Strategic Planning and

the Theory of the Firm," Journal of Marketing, 46 (Spring),

15-26.

Amdt, Johan (1978), "How Broad Should the Marketing Con-

/

Iniirnal nf MarLatin/i

Cnvinn ^Q0/

cept Be?," Journal of Marketing, 42 (January), 1O1-103Bagozzi, Richard (1974), "Marketing as an Organized Behavioral System of Exchange," Journal of Marketing, 38 (October), 7 7 - 8 1 .

(1975), "Marketing as Exchange," JournalofMarketing, 39 (October), 32-39.

Bamard, C. (1938), Functions of the Executive,

Harvard University Press.

Bartels, Robert (1970), Marketing Theory and Metatheor;.

Homewood, IL: Irwin.

(1974), "The Identity Crisis in Marketing,

of Marketing, 38 (October), 7 4 - 7 5 .

Bourgeois, L. J. (1980), "Strategy and Environment: A Conceptual Integration," Academy of Management Review. 5

(January), 25-39.

Bums, Tom and G, M. Stalker (1961), The Management of

Innovation, London: Tavistock.

Buzzell, R., B. Gale, and R. Sultan (1975), "Market Share:

A Key to ProfitahWity," Harvard Business Review, 51 (January-February), 97-106.

Catry, B. and M. Chevalier 0^74), "Market Share Strategy

and the Product Life Cycle," Journal of Marketing, 38 (October), 219-242.

Child, J. (1972), "Organizational Structure, Environment, and

Performance: The Role of Strategic Choice," Sociology, 63

(January), 2-22.

Dill, W. (1958), "Environment as an Influence on Managerial

Autonomy," Administrative Science Quarterly, 2 (March),

409-443.

Duncan, R. B. (1972), "Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty,"

Administrative Science Quarterly, 17 (September), 313-327.

Emery, F. E. and E. L. Trist (1965), "The Causal Texture of

Organizational Environments," Human Relations, 18 (Febmar>')> 21-32.

Fox, H. (1973), "A Framework for Functional Coordination,"

Atlantic Economic Review, 23 (November/December), 8II.

Galbraith, Jay (1977), Organization Design. Boston: AddisonWesley.

Hambrick, D., I. MacMillan, and D. Day (1982), "Strategic

AEtribute.s and Performance in the Four Cells of the BGG

Matrix—A PIMS-based Analysis of Industrial-Products

Businesses," Academy of Management Journal, 25 (September), 510-531.

Hansen, H. (1967), Marketing-Text Techniques and Cases,

Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Hatlcn, K. (1974), "Strategic Models in Brewing Industry,"

Ph.D. dissertation, Purdue University.

, D. Schendel, and A. Cooper (1978), "A Strategic

Model of U.S. Brewing Industry, 1952-1971," Academy

of Management Journal, 21 (December), 592-610.

Hofer. C. (1975), "Toward a Contingency Theory of Business

Strategy," Academy of Management Journal, 18 (December), 784-810.

Holloway, Robert J. and Robert S. Hancock (1973), Marketing in a Changing Environment, 2nd ed., New York: Wiley.

Hunt, Shelby D. (1976a), Marketing Theorv, Columbus, OH:

Grid.

—•(1976b), "The Nature and Scope of Marketing,"

Journal of Marketing. 40 (July), 17-28.

Katz, D, and R. Kahn (1966), The Social Psychology of Organizations, New York: Wiley.

Khandwalla, Pradip N. (1977), The Design of Organizations,

New York: Harcourt.

Roller. Philip (1972), "A Generic Concept of Marketing,"

Journal of Marketing. 36 (April), 46-54.

(1980), Marketing Management: Analysis. Planning, and Control, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

~— and Sidney J. Levy (1969), "Broadening the Concept of Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 33 (January),

" ~ 7 — a n d Gerald Zaltman (1971), "Social Marketing: An

'Approach to Planned Social Change," Journal of Market"'^35 (July), 3-12.

J. (1979), "Managing External Dependence," Acad'^f ^(f^agement Review. 4 (January), 87-92.

ce, Paul and Jay Lorsch (1967), Organization and Its

^?"'"^"'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

William (1969), "Marketing's Changing Social Rela-

tionships," Journal of Marketing, 33 (January), 3-9.

Levitt, T. (1965), "Exploit the Product Life Cycle," Har\'ard

Business Review, 43 (November-December), 81-94.

Luck, David J. (1969), "Broadening the Concept of Marketing

Too Far," Journal of Marketing. 33 (July), 53-55.

MacMillan, L, D. Hambrick, and D. Day (1982), "The Association between Strategic Attributes and Profitability in

the Four Cells of the BCG Matrix—A PIMS-based Analysis of Industrial-Products Businesses," Academy of Management Journal. 25 (December), 733-755.

Mazur, P. (1953), The Standards We Raise. New York: Harper.

(1958), "Progress in Distribution: An Appraisal after

Thirty Years," speech before the Thirtieth Annual Boston

Conference on Distribuiion.

McCarthy, E. J. (1960), Basic Marketing, Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Miles, R. and C. Snow (1978), Organizational Strategy,

Structure, and Process, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mintzberg, H. (1972), "Research on Strategy Making," Academy of Management Proceedings. 90-94.

Neghandi, A. and B. Reimann (1973), "Task Environment,

Decentralization, and Organizational Effectiveness," Human Relations. 26 (May), 203-214.

Patton, G. R. (1976), "A Simultaneous Equation Model of

Corporate Strategy: The Case of the U.S. Brewing Industry," Ph.D. dissertation, Purdue University.

Pfeffer, Jeffrey (1978), Organizational Design, Arlington

Heights, IL: AHM Publishing Corporation.

and G. Salancik (1978), The External Control of

Organizations. New York: Harper.

Porter, M. (1979), "How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy," Harvard Business Review. 57 (March-April), 137145.

—

(1980), Competitive Strategy. New York: Free Press.

Rink, D. and J. Swan (1979), "Product Life Cycle Research:

A Literature Review," Journal of Business Research. 14

(September), 219-242.

Rumelt, R. and R. Wensley (1981), "In Search of the Market

Share and Effect," Academy of Management Proceedings,

2-6.

Schoeffler, S., R, Buzzell, and D. Heany (1974), "The Impact

of Strategic Planning on Profit Performance," Harvard

Business Review. 52 (March-April), 81-90.

Scott, Richani A. and Norton E. Marks (1968), Marketing and

Its Environment, Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Shniptinc, F. Kelley and Frank A. Osmanski (1975), "Marketing's Changing Role: Expanding or Contracting," Journal of Marketing. 39 (April), 58-66.

Stidsen, B. and Thomas F. Schutte (1972), "Marketing as a

Communication System: The Marketing Concept Revisited," Journal of Marketing, 36 (October), 22-27.

Terreberry, S. (1968), "The Evolution of Organization Environments," Administrative Science Quarterly, 12 (March),

590-613.

Thompson, J. D. (1967), Organizations in Action, New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Wasson, C. (1974), Dynamic Competitive Strategy and Product Life Cycles. St.'Charles, IL: Challenge Books.

Webster, F. E. (1981), "Top Management's Concern about

Marketing: Issues for the 198O's," Journal of Marketing,

45 (Summer), 9-16.

Wind, Y. and Thomas S. Robertson (1983), "Marketing Strategy: New Directions for Theory and Research," Journal of

Marketing, 47 (Spring), 12-25.

Zoltners, A. A. and J. A. Dodson (1983), "A Market Selection Model for Multiple End-Use Products," Journal of

Marketing, Al (Spring), 76-88.

Environmental Management / 53