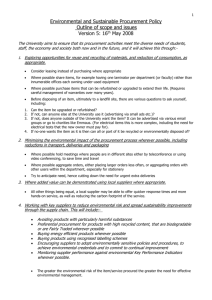

Organisation of Purchasing and Buyer-Supplier

advertisement