Understanding Mobile Phone Impact on Livelihoods in Developing

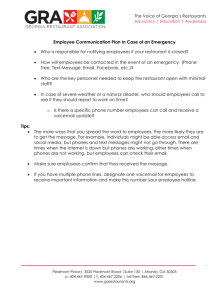

advertisement