Protecting Private Property Rights: Reforming Eminent Domain in

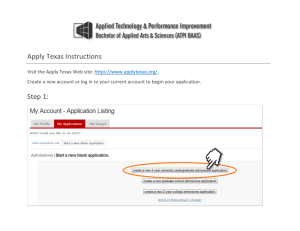

advertisement