ýýý /4)

advertisement

TOPOGRAPHIES OF POWER

IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES

EDITED BY

MA1'KE DE JONG Ai\TDFRANS THEUAVS

I\TTH

CARINE VAN RHIJN

BRILL

LEIDEN "BOSTON "KÖLN

2001

ýýý

/4)

ONE SITE, MANY N,IEANINGS:

SAINT-MAURICE D'AGAUNE AS A PLACE OF POWER

IN THE EARLY IkIIDDLE AGES'

Barbara H. Roscmrcin

I

`Great is the power (Limos)at the tombs of the [Theban] martyrs'

wrote Gregory of Tours about the site of the saints buried at the

monastery of Saint-Maurice d : Agaune 2 What sort of power did they

have? The answer is hardly simple. Nor is it the same for all time.

Since the power at the tombs was believed to be the power of God,

it demanded recognition, deference, and monumentalization. These

acts in turn intensified and complicated the ways in which the site's

power was understood. And, in yet another turn, those who tapped

into and associated themselves with the place hoped to - and apparently did - enhance their own power and prestige. This paper is

an exploration of the changing ways in which beliefs about the power

at Agaune led people rulers, bishops, monks, and occasionally

ordinary people - to reorganize and make use of the site and to

institutions

other

model

upon some of the key features of the monastery

built there.

Agaune's very emplacement made it powerful for worldly reasons.

High upon a rocky cliff close to the Rhone river, about 40 km from

the Great Saint Bernard pass, it was a strategic point between Italy

and the north. This meant different things at different times: in the

Roman period, Agaune was atoll-collection centers in the Burgundian

II am grateful to the members of the Bellagio workshop, and in particular to

Albrecht Diem, Janet L. Nelson, Julia M. H. Smith, Ian Wood and, above all, Mayke

de Jong for their important suggestions. I thank Aless:mdn Antonini, Charles Bonnet,

and Francois Wible for their generous help in introducing me to the archaeology

of Agaune. Christian Sapin supplied much-needed general orientation. Loyola University Chicago Research Services awarded me a Summer and Research Grant in

1998, which made it possible to for me to visit the site and write up my findings.

Loyola University Center for Instructional Design (LUCID) ably drew the figure.

1 Gregory of Tours, Libor in gloria marpirum, c. 75, B. Krusch ed., NIGH SRLI I,

pt. 2 (Hannover, 1885, rev. 1969), p. 87: Ikgza es1ewbn rirhu ad antediclonan marlyrum sepulchra.

4 M. Zufferey, Die Abtei Saint-Maurice d': lgaune inn IiodmriUelaher (830-1258),

272

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

it

demarcation

Merovingian

point, separating the

a

periods,

was

and

Italian south from Europe's northern kingdoms; in Charlemagne's

hinge,

it

connecting the conquered peninsula

a

symbolic

was

empire,

Its

Franks.

kingdom

Italy

the

to

the

geo-political position was

of

of

Agaune's

backdrop

to

the

numinous powers.

always

Unexpected springs of water spout from crags on the site. Pagan

Romans, who incorporated aquae into their topographies of power,

dedicated Agaune to the nymphs. ' The Christians followed suit in

their own way. The PassioAcaunensiummarlyrum by Eucherius, bishop

fifth-century

Christian(d.

450/4),

Lyon

the

the

version

of

gives

us

of

ization of Agaune: Roman imperial troops from Thebes, called up

by emperor Maximian at the end of the third century, and led by

their commander Maurice, were decimated near Agaune for refusing to kill Christians in the vicinity. 5 Their bodies were discovered

later,

Eucherius

by

Theodore,

bishop

tells

us,

of Marabout a century

tigny (then known as Octodorum). Theodore, disciple of Ambrose, and

by

latter's

Saints

Gervasius

be

the

to

appropriation

outdone

of

not

6

basilica

Protasius,

Agaune

in honor of Maurice

constructed

a

at

and

`now

looming

his

the

nestled

against

associates

and

rock, leaning

'

just

it

one

side'. As we shall soon see, this description in

on

against

the Passioinspired a compelling - but wrong - modern interpretation

of the archaeological evidence.

A whole monastic complex, probably dual sex, grew up around

the tombs of the martyrs and served the pilgrims who came there.

We know about this community, however, only from Eucherius's

Passio,the anonymous Life and Rule of the Jura abbots, and the equally

anonymous Vita of Saint Severinus 8 Subsequent written sources made

a conscious effort to suppress - or in any event keep mute about this early monastery.

des Max-Planck-Instituts

fiir Geschichte 88 (Göttingen, 1988),

Veröffentlichungen

p. 29, n. 26.

4 An altar dedicated to the nymphs dating from the third century was found

on

the spot. It remains today in the vestibule of the abbey.

5 Eucherius, Passio Acaunensium martyrum, c. 2, B. Krusch ed., NIGH SR

'J 3

(Hannover, 1896), p. 33. Eucherius was almost certainly substituting Maximian for

Constantius Chlorus, father of Constantine, thus writing the latter out of the story

of Christian persecution.

6 P. Brown, The cult of the saints: Its rise and function in Latin Christianity (Chicago,

1981), pp. 36-7.

1 Eucherius, PassioAcaunensiummartyrum, c. 16, p. 38: `basilica, quae uastaenunc adiiacet'.

latere

tantum

adclinis

uncta rupi, uno

8 Vita Severini abbatis Acaunensis,B. Krusch ed., MGH SRiMI 3 (Hannover, 1896),

SAINT-MAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

273

In 515 Sigismund, a Burgundian prince fairly newly converted

from Arianism to Catholic Christianity, rebuilt and reorganized the

site with the help of his episcopal advisors .9 To Agaune's fame as

the place of martyr-soldiers, new sources of power were now added.

They included the new monastery's extraordinary day-and-night liturgy,

which the monks carried out in relay; its symbolic embodiment

of an episcopal-royal alliance; and, soon, its stewardship of the first

royal saint in the 'Vest. For, about ten years after Sigismund and

his wife and sons were killed by the Franks in 523, the abbot of

Saint-Maurice retrieved their bodies and buried them in a church

"

his

monastery. By 590, according to Gregory of Tours, the

near

king was consorting with saints and Masses said in his honor were

"

working miracles.

Saint-Maurice thereafter became a model monastery for Burgundian

kings. When King Guntram founded Saint-Marcel de Chalon, he

had Saint-Maurice in mind; and when Dagobert reformed his favorite

Saint-Denis,

he too had the. exemplar of Agaune in view. 12

monastery,

The Carolingian period brought changed status to the monastery

when, in the ninth century, Saint-Maurice became a house of canons.

Nevertheless, it still maintained a reputation for holy power, and in

888 Rudolf chose the spot for his coronation as king of Burgundy. 13

What was so compelling about the place? Certainly Frederick

Paxton is not wrong to stress the cult of Sigismund, healer of fevers

first

illness.

Nor is Friedrich Prinz wrong

the

patron

saint

of

an

and

pp. 168-70; iru des Peresdu Jura, F. Martine ed., SC 142 (Paris, 1968). On dating

the latter text to just before 515 and on the general silence regarding this pre-515

community, see: r. Masai, "La `iota palrunr iurerrsiunr' et les debuts du monachisme

ä Saint-Maurice d'Agaune", in: J. Autenrieth and F. Brunhölzl eds., Festschri Bernhard

Bischoff zu seinem 65. GeburLttag(Stuttgart, 1971), pp. 43-69.

9 Nevertheless, the title of Avitus's Homily 24, Dicta in basilica sanclonunAcauneruitmm,

in innovation monasterii, shows that the church was being `revived', not founded; see

Avitus of Vienne, Homilia 24, in: U. Chevalier ed., Oacvrescornplllesde saint Avit k que

de Vienne(nouv. ed., Lyon, 1890), p. 337.

10 Gregory of Tours, Decenr libri kistorianent, 111, c. 5, B. Krusch and AV. Levison

eds., MGH SRM 1, pt. I (Hannover, 1951), p. 101.

11 See F. S. Paxton, "Power and the power to heal: the cult of St Sigismund of

Burgundy", Fe11E 2 (1993), pp. 95-110; Gregory of Tours, fiber in gloria marynun,

c. 74, p. 87.

12 For Guntrum, sec below, at note 36; for Dagobert, sec note 39.

13 Zufferey, Die Abtei Saint llauri a d'Agaune, p. 95. Rudolf I was lay abbot of Saint.

Maurice before becoming king of Burgundy; see Rcgunr Burgundiae e stirpe Rudolfina

Diplomata et Acta, eds. T. Schielfer and H. E. Mayer = Die Urbunden der Burgundischen

Rudolfinger(München, 1977), p. 93, n" 1.

274

BARBARA

H.

ROSENNEIN

its

liturgy

and

popular

the monastery's extraordinary

" All of this is true; but it is not the

himself.

Maurice

martyr-saint,

because

it

Agaune

than

meant

more

one

powerful

truth.

was

whole

The

in

different

different

things

contexts.

remainthing, and sometimes

der of this paper will elaborate on this point, highlighting those few

both

the

material and written - seem to

sources moments when

to highlight

cluster closely enough to allow us to say something reasonable about

Sigismund's

foundation;

These

the

time

the

of

them.

moments are:

Guntram;

King

the mid-seventh century; and the early

of

reign

Carolingian period.

SIGISAIUND'S

FOUNDATION

The foundation of Saint-Maurice marked the start of an orthodox

(i. e. catholic) royal-episcopal alliance. Indeed, I have argued elsein

the

that

many ways a creation of the epismonastery

was

where

I

liturgy,

"

Agaune's

In

dubbed

that

that

same

study,

argue

copacy.

the laus perennisby modern commentators, has been wrongly attribAkoimetoi

the

the

to

staunchly

orthodox

of

model

monks at

uted

Constantinople. The only man associated with Agaune who might

have been in a position to know about those monks was Avitus,

bishop of Vienne and advisor to Sigismund and his father, King

Gundobad. But Avitus's letters show him to be thoroughly confused

Constantinople,

to

not

orthodox

at

what was and was

especially

as

On

liturgical

the other hand, Avitus and the

practices.

regarding

Sigismund

in

Agaune's

foundation

involved

bishops

with

other

need

have looked no further than the practices of bishops and monks in

the Rhone Valley to find extraordinary liturgical innovation. There

for

liturgy

home

day-and-night

of

at

a

right

precedent

psalmody.

was

When Sigismund founded Agaune, he had good political reasons

for favoring the Theban martyrs. His cousin Sedeleuba and his aunt

Theudelinda had already founded churches near the city of Geneva

14 Paxton, "Power and the power to heal", esp. pp. 105-9; F. Prinz, Fril/res

Mönchtum im Frankenreich.Kultur und Gesellschaftin Gallien, den Rheinlanden und Ba) ern an

Beispiel der monastischenEntwicklung (4. bis 8. Jahrhundert) (2nd ed., München, 1988),

pp. 102-12.

15 B. H. Rosenwein, "Perennial prayer at Agaune", in: S. Farmer and B. H. RosenReligion in medieval society (Ithaca, N. Y.,

Monks

and

outcasts:

saints

and

nuns,

wein eds.,

2000), pp. 37-56.

SAINT-AMAURICE

D'AGAUN'E

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

275

dedicated to Ursus and Victor, martyrs associated with Maurice. "

Sigismund thus may have been, in the words of Ian Wood, `intent

"

In this he resembled the

his

the

relatives'.

works of

on eclipsing

bishops of Geneva, who also took keen interest in the cult. Bishop

Domitianus was known for having transferred Victor's bones to

Geneva as well as for his discovery and invention of the relics of

Innocentius, another Theban martyr. "' And Bishop Maximus, acVita

to

the

cording

abbatumAcaunensium,was the advisor who `incited'

Sigismund to oust the `vulgar' crowd at Agaunc and reorganize the

for

in

the martyrs, even though Agaunc was not

a

way

suitable

site

in Maximus's diocese.' This suggests that the bishop of Geneva may

have been interested in redrawing jurisdictional as well as spiritual

boundaries.

Bishops and prince together, then, reconfigured the topography of

the holy, setting up a monastery that suppressed an older community of worshippers at the martyrs' tombs while drawing upon a

large local repertory of cults and cultic practices for the new monastic ordo there. The new monks still tended the relics of the Theban

but

they did so in a different way, and in entirely new

martyrs,

buildings.

This was not recognized in the 1940s and 1950s, when the archaeologist Louis Blondel confidently asserted that he had found the preSigismund edifices: a chapel, later enlarged into a basilica built over

the martyr's tombs against the rock; an attached baptistery; and a

hospice for pilgrims. He also found structures that he took to be

Sigismund's basilica, and he interpreted a ramp that led around the

southern and western walls of that new basilica as a pathway by

16 For Theudelinda, see: Passio S. 1tcloris d Sociorum,c. 2, AASS, September VIII,

p. 292; for Sedeleuba, see: Fredegar, Chronira, IV, c. 22, B. Krusch ed., NIGH SRNI

2 (Hannover, 1888), p. 129; L Blondel, "Le prieurc Saint-Viictor. Les debuts du

christianisme et la royaute burgonde ä Geneve", Bulk in dt la socüli d'hisloire et

d'archiologie de Geneve11 (1958), pp. 211-58; I. N. Wood, "Avitus of Vienne: ReliD.

diss.,

in

Rhone

Valley,

470-530"

(Ph.

Auvergne

the

the

and

culture

and

gion

Oxford, 1980), pp. 208-9.

'r Wood, "Avitus of Vienne", p. 217.

is Passio S. Irutorit el sociorum,c. 2, p. 292; Euchcrius, Passio acaunauiunt rnartynun,

appendix 2, p. 41; Wood, "Avitus of Vienne", p. 209.

19 Vita abbatumAcaunensium,c. 3, B. Drusch cd., NIGH SRNI 3 (Hannover, 1896),

incidrrotionan

Sigýinnundi

bare

Cenmensis

`Maximus

176:

pratcordia

urbis atlislts...

ad

p.

ornaverant,

tavit, ut de loco illo, quernpreliosa incite 7htbati marines it fuione sarýgpuinis

...

promiscui vulgi cormnixta lurbilatio tollotlur, el... alloy habilattium rantarel'.

276

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

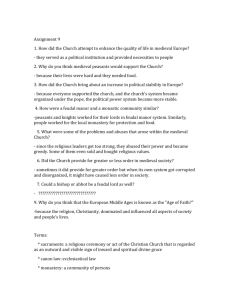

tllnnrlnl'e

pre-515 basilica

II

Carolingian church

westernapse

ý

)

Blondel's

pre- 515 baptistry

Carolingian church

easternapse

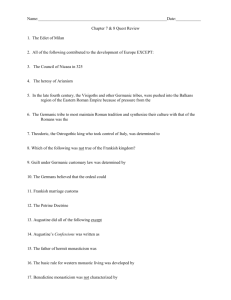

Pig. 1. Saint-Maurice d'Agaune, fifth to the ninth centuries (schematised plan,

adapted from Blondel 1948, figs. 2,3 and 5).

basilica,

to

the

old

access

under which was

which pilgrims gained

the primitive mausoleum (fig. 1).20

We have to thank several trees and their destructive roots for causing an emergency that sent new archaeologists led by Hans Jörg

Lehner to the site in 1995/96.21 It should be said from the outset

that their reassessment is extremely preliminary, mostly unpublished,

They

incomplete.

were able to revisit only the site

and, above all,

that Blondel had chosen to excavate, and that is probably too rebuildings

The

church

and

of the complex take up

present

stricted.

a good deal of space below and to the southeast of Blondel's excavation area. But when the present community at Saint-Maurice

decided to expand their church in the 1940s, Blondel observed very

20 Blonde! published numerous articles on Saint-Maurice beginning in the 1940s

The

important

include:

1960s.

L.

into

Blonde], "Les ancithe

most

continuing

and

Etude

Vallesia

d'Agaune.

3 (1948), pp. 9-57 and

basiliques

archeologique",

ennes

"Apercu sur ]es edifices chretiens dans la Suisse occidentale avant Pan mille", in:

FrühmittelalterlicheKunst in denAlpenliindern- Art du haul mq en 4e dans la region alpine

Arle dell'alto medioevonella regionealpina, Acles du III` congresinternational pour I'elude du

haul mojen age, 9-14 septembre1951 (Olten, 1954), pp. 271-308, at 283-9; on the

basilique d'Agaune. Une rectification",

d'acces

la

a

"La

Blondel,

rampe

ramp, see

Vallesia 22 (1967), pp. 1-3.

in: F. Wible ed., "Chronique des decouvertes

21 H. J. Lehner, "Saint-Maurice",

le canton du Valais en 1995", Vallesia 51 (1996), pp. 341-4.

dans

archeologiques

SAINT-MAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

277

clearly (before it was covered over by modern structures once again)

the remains of an ancient (perhaps sixth-century) baptistery and an

22

is

It

tomb.

thus very likely that the early architectural

eighth-century

Agaune

at

group

was considerably larger and more complex than

the one now on view, extending into the area now covered by modern edifices. Saint-Maurice was, after all, meant to showcase the

bishop

king

bishops

his

the

time

nearby

piety of a

and

at a

when

of Martigny had a huge ecclesiastical complex boasting two large

churches side-by-side, " and when the bishop at Geneva presided

over a still more impressive compound, with two differently organized

basilicas marking out its northern and southern flanks; a baptistery;

and a grand episcopal reception hall fitted out with a magnificent

his

2}

floor.

It

is

tile

that

episcopal

mosaic

a royal scion and

unlikely

advisors envisaged less for their common enterprise. 25

So what we see is hardly what was there. And yet what we see

is enormously suggestive. It suggests, in the first place, that nearly

everything that had been built before 515 was obliterated, whether

by chance or design. What Blondel took as the evidence for the pre515 basilica - an apse wall - turns out, upon modern inspection, to

be a Romanesque or, more likely, Gothic building. The baptistery

that Blondel had identified off the south wall of the basilica turns

out to have been a sacristy attached to the later Carolingian church

built on the site; while the `mausoleum' that Blondel had thought

had

first

the

the

tombs of the martyrs, over which

chapel

contained

11 See the `state of the question' and discussion of the date of this baptistery in

F: O. Dubuis and A. Lugon, "Les premiers siecles d'un diocese alpin: recherches,

acquises, et questions sur l'evCChe de Sion", pt. 3: "Notes et documents pour servir

A 1'histoire des origines paroissiales", l'allesia 50 (1995), pp. 135-9.

23 H. J. Lehner and F. Wible, "Martigny VS: De la premiere cathedrale du Valais

A la paroissiale actuelle: la contribution

de l'archeologie", Helvetia Archaeologica 25

(1994-98), pp. 51-68, esp. 60-64.

24 C. Bonnet, Les fouilles de l'ancien groupe episcopalde Geneve(1976-1993), Cahiers

d'archeologie genevoise 1 (Geneva, 1993). I thank Professor Bonnet for a splendid

tour of the excavations. In general, the Burgundian region - including the sees of

Vienne, Valence, and Lyon boasted tri-partite episcopal compounds (i. e., two

cathedrals plus baptistery) at this period. See J: F. Reynaud, Lyon (Rhone) aux premiers temps chreliens. Basiliques et necropoles.Guides archeologiques de la France 10

(1986), esp. pp. 29-30,89-97.

25 This may be especially true given the association of Theodore with Ambrose:

Ambrose's Milan had a double cathedral, as did many late antique Lombard episcopal sees; see P. Piva, Is cattedrali lombarde.Ricerchesulle `cattedralidoppie' da SantAmbrogio

all'eth romanica (Quistello, 1990), esp. chap. 2.

278

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

been erected, in fact contains only three tombs: one dates from before

515 while the others are later (though pre-Carolingian). Some few

hospice

for

be

Blondel

the

to

pilgrims

pre-515

considered

walls that

Lehner

his

(according

the

and

group) propof

to

observations

are

function

is uncertain. The

but

be

dated

their

that

to

period;

to

erly

Blondel

buildings

the

right

are

church of

that

plausibly

got

only

Sigismund (with its subsequent expansions) and the Carolingian church

with its eastern and western apses.

Nothing, therefore, suggests the pre-515 community or any of its

in

fact

it

is

the

that

to

think

tempting

site

was

reorstructures, and

Sigismund.

in

Certainly

the

time

of

possible

ganized as completely as

hid

foundation

the

and obfuscated the existence

texts

new

the

about

But

lived

the

the

on

site.

need the architecearlier monks who

of

in

its

Let

the

texts?

the

matter

ture mirror

us put

simplest form: on

the basis of our present knowledge of the site, there is no trace of

It

is

have

`against

been

basilica

the

that

possible

rock'.

we

an early

looking in the wrong place; in that case, we might say simply that

Sigismund and his advisors erected a prestigious new church withit

Alternatively,

is

first

that

to

the

the

possible

old.

reference

out

basilica was where Blondel sought it, but was obliterated deliberately

by Sigismund's architecture. Finally, it is just possible that the early

basilica never in fact existed.

Whatever the case, the absence of the oldest structures does not

Charles

Bonnet

fact

the

that,

pointed out to me, there is

as

obviate

In

long-term

the

at

site.

particular, two `hot'

continuity

evidence of

One

discerned.

be

ran north-south along a line marked

zones may

by the eastern apses of a sequence of churches built on the site up

to and including the Carolingian period. (It was signaled, as well,

by the Gothic apse next to the rock). The other ran parallel to, but

to the west of, the first. For the earliest period, this western axis is

bit

by

But

the

smallest

of

wall.

only

we can see

clearly represented

it as a focal point in the Carolingian period, when an entire westinto

built,

Saint-Maurice

the

tomb

placed

which

was

of

ern apse was

by

topped

space

a

rectangular

an

arcosolium,

an archway. This

within

western axis may not have been neglected by Sigismund's church

either, as we shall see.

We can associate that latter church with the constructions that

Lehner calls `phase 2', which appear to date from the sixth century.

Blondel confidently spoke of 'Sigismund's church', and in this instance

he may not be wrong. We know that Sigismund's church was ded-

SAINT-MAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

279

icated in 515, and we have a homily written by bishop Avitus for

the occasion. 26 There Avitus calls attention to the psalmody of the

monks; he even makes up a word, psalmisonum, to emphasize the

solemn tones of the day and night liturgy there. Unfortunately, he

does not describe the church in which this liturgy took place; but

Blondel was right to think that it was a simple basilica with one

fairly elongated eastern apse.27 Blondel also thought that flanking it

to the south and gradually rising along its west end was a ramp

leading to the old basilica of the pre-515 monks. It now seems more

likely that the ramp led right into Sigismund's church. Why would

pilgrims care to enter there? I have two complementary suggestions.

First, they entered to marvel at the monks' non-stop liturgy. It is

striking that no barrier has been discovered between the area around

the altar and the rest of the basilica, for such structures were com28

Gregory

Tours

in

Indeed,

this

suggests

mon

churches of

of

period.

that laypeople were welcome to come to Agaune and listen to the

monks. His first illustration of the virtus of the tombs of the martyrs,

quoted at the beginning of this paper, features Saint Maurice comforting a mourning mother on the spot by inviting her to rise for

`among

for

her

dead

listen

day

the

the

to

son

matins

voice of

next

the chorus of psalm-singing monks'. She could do this `every day of

[her] life' if she liked. "

Second, pilgrims entered only after going round the west end of

the church. This may have been to allow them to visit, in some way

we cannot now determine, the relics (if such there were) along that

western axis. Certainly it is striking that a bit later another corridor

was built, wrapping itself right around the ramp, under which are

tombs that appear to date from the eighth and ninth centuries. This

was clearly a privileged burial place. But here we are getting ahead

of our story.

To return to the foundation of 515, then, the sources, both textual and material, suggest two preoccupations. One was to forget

26 On the date of the foundation, see J: M. Theurillat,

L'Abbaye de St-Maurice

d'Agaune des origines ä la refonne canoniale, 515-830 enuiron = Pallesia 9 (1954).

27 Lehner, "Saint-Maurice",

modifies the sequence of apse construction, however.

28 See Bonnet, "Groupe episcopal de Geneve", pp. 38-9, and F. Oswald,

L. Schaefer, and H. R. Sennhauser eds., l'orronnanisclien

Katalog der Denlann'ler

A rchenbauten.

bis zum Ausgang der Ottonen, 2 vols. (München, 1966-1971, reprint 1991).

29 Gregory of Tours, Liber in gloria martyrum, c. 75, p. 88.

280

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

the first community that had tended the relics of the martyrs. The

ingenuity

through

to

episcopal

and royal power create

was

other

liturgy

long

bishthat

the

the

would

express

piety

of

a spectacularly

deference

to the site and glory to

appropriate

according

ops while

the king.

THE

TIME

OF KING

GUNTRANI

The texts for King Guntram show that the alliance between bishMerovingians

kings

the

took over Burgundy

when

persisted

ops and

Agaune

that

remained a potent symbol of close royal-episcopal

and

relations. 30 Gregory of Tours could hardly mention Agaune without

invoking the piety of kings. In his Histories, he associated the site

King

Sigismund, penitent murderer of his own

the

of

remorse

with

in

Liber

he

In

linked

it as well to King

the

gloria

martyrum,

son.

Guntram, Frankish king of Burgundy (561-92). Indeed, in Gregory's

second (and last) illustration of the virtus of the tombs of the Theban

martyrs, he dwelt on Guntram's `spiritual activities', his renunciation

his

and

gifts to the monks at Agaune.

of earthly pomp,

For Gregory, Guntram was a bishop manque.Indeed, he was another

Mamertus, the bishop of Vienne who (as Ian Wood describes in this

volume) created a new kind of rogation liturgy in the face of natural disasters:

as if a good bishop [Gregory writes] providing the remedies by which

the wounds of a common sinner might be healed, [Guntram] ordered

all the people to assemble in church and to celebrate Rogations with

For three days, his alms-giving flowing more

the highest devotion....

than usual, he was so anxious about all the people that lie might well

have been thought not so much a king as a bishop of the Lord. 31

At the Council of Valence in 585, Guntram's bishops met `on account

of the complaints of the poor' to decide what would be best `for the

safety of the king, the salvation of his soul, and the state of religion'. 32 It is clear by the end of the document that the `poor' were

the monks of royal monasteries; or, more precisely, they were the

3o Pace Paxton, "Power and the

3i Gregory of Tours, Decem libri

Valentinum",

in:

32 "Concilium

1980), p.

CCSL 148A (Turnhout,

power to heal", p. 107.

historiarum, IX, c. 21, p. 441.

C. de Clercq cd., Concilia Galliae, a.511-a. 695,

235.

SAINT-MAURICE

i

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

281

monks of monasteries favored by King Guntram, Queen Austrechildis,

and their two daughters, the latter three now deceased. The council confirmed the gifts to loci sancti by these royal personages and,

its

calling

assent not simply worthy of bishops but a matter of divine

inspiration, turned to consider how to protect the basilicas of SaintMarcel and Saint-Symphorian and other places endowed by royal

largesse. It declared that whatever the royal family had given or

would give to these places - `whether in the ministry of the altar

for the divine cult' - was

or in gold and silver ornaments (speciebus)

not in future to be diminished or taken away either by the local

bishop or by royal power (potestasregia), on pain of perpetual anathema. Here the alliance of king and bishops had become so intense

as to lead them to proclaim a mutual and complementary selfimpetus

In

the

the

of a reform

restraint.

mid-seventh century, under

movement spearheaded by the disciples of Columbanus, this self33

interpreted

formal

be

to

restraint would come

as

exemption.

THE

MID-SEVENTH

CENTURY

In the mid-seventh century Agaune had two related meanings: liturfor

for

its

juridical.

lauded

liturgy

It

gical and

and renowned

was

its monastic exemption, which betokened its excellent relations with

kings.

The liturgy is easy to deal with: Fredegar, for example, writing

in the mid-seventh century, 34 speaks of the psalmody of Saint-Denis

ad instar - on the model - of Agaune. 35 The long day and night

liturgy at Agaune continued to exert its magnetic attraction.

Exemption is more complicated and involves a new kind of royal

Sigismund.

from

divorced

that

though

of

model,

one not entirely

The new model, however, went beyond linking king to episcopacy:

the king himself became pliant and bishop-like. When Fredegar tells

us that in 584 King Guntram founded Saint-Marcel de Chalon on

the model of Saint-Maurice, what he means (as he goes on to say)

33 On these disciples, see B. H. Rosenwein, JVegotiatingspace:Power, restraint, and privilegesof immunity in earn, medievalEurope (Ithaca, N. Y., 1999), chap. 3.

" W. Goffart, "The Fredegar problem reconsidered", in: idem, Rome'sfall

and

after (London, 1989), p. 322, dates Fredegar c. 658.

ss Fredegar, Cltronica,IV, c. 79, p. 161.

282

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

is that Guntram, thinking like a bishop, called a council of bishops

to carry forward the task. 36 Fredegar had in mind the Council of

Valence. But by Fredegar's day, some of the words of this council

had been incorporated into the first charter of exemption, that for

Rebais. And Saint-Marcel itself was understood to be a precedent

for the Rebais exemption. The privilege for Rebais, drawn up c. 640,

presents Burgundofaro, bishop of Meaux, as initiating a series of

his

diocesan

directed

own

provisions

powers of jurisdiction

against

In

Rebais.

the

the first of these provisions, as

over

monastery of

Albrecht Diem pointed out to me, the ideas and even the vocabulary of the Council of Valence appear: whatever is given to the

is,

that

that pertains to the divine cult or funcmonastery, whatever,

tions as offerings for the altar, is not to be usurped or diminished

by bishops or kings (regalis sublimitas). Diem concludes that `Rebais

is a sort of mega-extension of Valence'. 37

Rebais's is the first extant privilege containing an episcopal exemption. Indeed, it is probably the first ever drawn up. Yet it places

itself within a venerable monastic tradition that begins with SaintMaurice. Its provisions of `exemption' (libertas), it declares, arise

not

from mere `impulse' (instinctu)but rather from the norms of the `holy

places' of Agaune, Urins, Luxeuil, and Saint-Marcel of Chalon.

How can this be? There are no charters of exemption for

any of

these monasteries prior to the one given to Rebais. I suggest that

the new mid-seventh century understanding of the right relations

between a special, royal monastery and the king and his bishops

was

read back to the time of Agaune's foundation. Fredegar thought that

Guntram followed the model of bishops when he

was with bishops:

`sacerdusad instar'.36 He noted that Guntram called a synod

of forty

bishops `ad instar institucionis monasterii sanctonim Agauninsum', that is,

following the example of the foundation of Agaune, which (this

was

Fredegar's point), in the time of Sigismund was confirmed by Avitus

and other bishops upon the orders of the prince. For Fredegar, then,

Saint-Marcel followed the model of Agaune because it involved

a

king who acted according to the model of bishops and who ratified

his foundation through them. Agaune became a `type' of

exempt

3c Fredegar, Chronica, IV, c. 1, p. 124.

37 Quoted from a private E-mail communication.

note 32 above.

38 See Goffart, "Fredegar problem", p. 343.

For the Council of Valence

see

SAINT-MAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

283

monastery through a chain of associations that led from Rebais back

to Saint-Marcel and the Council of Valence, and from thence back

to Agaune.

In 654, just a few years before Fredegar was writing, Clovis II

issued a diploma for Saint-Denis that neatly tied together the newstyle royal patronage with both exemption and the non-stop liturgy

at Agaune. 39 Itself a confirmation of an episcopal exemption that

for

Rebais,

Sainthave

been

Burgundofaro's

the

to

must

very close

Denis privilege linked the king's interests with those of the bishops,

and it ended with a reminder that King Dagobert, Clovis's father,

had instituted at Saint-Denis `psalmody per turns, just as it is practiced at the monastery of Saint-Maurice d'Agaune'. These various

ideas came together because of the mid-seventh century conviction

that episcopal exemption freed the monastery to carry out its liturin

kingdom'.

The

`for

the

the

the

gical round

emphasis

stability of

i

mid-seventh century was on the king as an associate of episcopal

sponsors who guaranteed the monastic liturgical enterprise by staying clear of the monastery.

This perspective is echoed as well in the papal exemption for

Agaune, issued in the mid-seventh century by Pope Eugenius I

(654-657). In this text, as reconstructed by Anton, the pope writes

his

behest

Clovis

(`postulavit

Chlodoveus'),

II

the

at

presenting

of

a nobis

Sigismund

King

words as confirmation of the statutes and privileges of

and the kings who came after him .40 The right of the brethren to

dioceis

the

their

choose

own abbot

affirmed, and the pope prohibits

san bishop from extending his ditio or potestas over the monastery;

by

it

invited

diocesan

the abbot to

the

nor may

even enter

unless

it

Mass;

he

to

the

take

given

alms

celebrate

nor may

away any of

by the faithful; nor, finally, may he carry off the tithes which, says

the privilege, were given to the monastery by the founder, now styled

`Saint Sigismund'.

By the late seventh or early eighth century, the idea that Agaune

formuin

`hands

its

diocesan

bishop

the

to

was

off'

was enshrined

lary of Marculf, where Agaune again paraded with Urins and Luxeuil

ss Chartae Latinae Antiquiores:" Facsimile-edition of the Latin chartersprior to the ninth cenlug, eds. A. Bruckner and R. Marichal, Part XIII, France I, H. Atsma and J. Vezin

1981), pp. 36-7, n° 558.

eds., [henceforth Chbl] vol. 13 (Dietikon-Zürich,

+o H. H. Anton, Studien zu den hloslerpriuilegiender Päpste im frühen Mittelalter. Beiträge

zur Geschichte und Quellenkunde des Dlittelalters 4 (Berlin, 1975), pp. 12 and 115.

284

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

"

Indeed,

befor

the

association

exemption.

episcopal

as precedents

first

diploma

for

Farfa,

Charlemagne's

In

routine.

came general and

for example, the monastery received a privilege said to be on the

(in

Luxeuil,

Agaune,

Urins,

for

the words

namely

and

model of those

of the charter):

for

bishop

the election of the abbot; nor

a

gift

receive

that no

should

have power to carry away from the monastery the crosses, chalices,

patens, books or anything else pertaining to the ministry of the church;

nor have the least power to subject the monastery to princely taxation; nor, finally, be able to exact tribute or a census from that monastery of theirs 42

Thus, in the mid-seventh century Agaune was a place of power not

Rhone

Frankish

its

the

the

as

at

on

royal court,

site

so much at

dual

liturgy

its

as

exemplar

symbolism

of

effective

neat

where

it

episcopal

of

and

royal

synergy

particular

and as model

- gave

bishops

kings

and

were creating the first charters of

panache when

immunity.

and

exemption

This view of royal/episcopal/monastic

relations did not last; the

privilege for Farfa marks the last gasp of the Merovingian tradition

of according episcopal exemptions to monasteries. Already by the

bishops

had

virtually stopped giving out episcomid-eighth century

Carolingian

In

the

period, kings gave out both

pal exemptions.

immunities,

but

they changed their character. By

and

exemptions

the addition of tuitio (protection), they asserted not as in the

hands-off policy but rather their very active

Merovingian period -a

hands-on control over the monasteries of the empire. 43

THE

CAROLINGIAN

ERA

a different aspect of Agaune was gaining new emphasis:

the organization of the monks into turmae (companies) to carry out

Meanwhile

41 Marculf, Formulae, I in: A. Uddholm ed., Alarcu!fiformularum libri duo (Uppsala,

1962), p. 20, n° 1.

42 Diplornata harolinorum, E. Mühlbacher ed., MGH DD I (2d ed., reprint Berlin,

1956), p. 141, n° 98 (775): `... ut nullus fpiscoporumpro electioneabbatis dationem accipere

debeatet potestalemnon habeat de ipso monasterioauferre crucescalicesPatenas codicesvel reliipsum

de

f

nec

ministerio

fcclesi

monasteriun:sub tributo ponereprincipum polesres

quas quaslibet

tatem minime haberel nec denuo tributum auf censum in supradicto monasterio eorum exigere

debeat... '

43 See Rosenwein, Negotiating space,Part 2.

SAINT-TIAURICE

i

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

285

their day-and-night liturgy in a church which itself had become all

the holier by organizing in focused fashion the translated relics of

the martyrs. The sources here are both material and textual. They

include the new Carolingian structures at Agaune itself

and the socalled foundation charter of King Sigismund, which Theurillat has

shown was a forgery of the late eighth/early ninth centuries. The

Passio sancti Sigismundi and the Nita SadalbergaeI also take to be

Carolingian. Though based on sixth-century materials, they

may help

us to assess the meaning of Agaune in the late eighth and early

ninth centuries.

In the early Carolingian period, Sigismund's church, which had

meanwhile undergone several changes and expansions at its east end,

was knocked down and subsumed into a far larger basilica with two

apses, the western one of which had a crypt below. 44 The focus of

this western end was the tomb of Saint Maurice, which was placed

in an arcosolium within its western wall. Though Lehner's findings

suggest that the old access ramp was destroyed at this time, it seems

that the passage-way that limned it, while no longer opening onto

the new church, was nevertheless fitted out with windows or apertures. These might have provided pilgrims with contact of some sort

with the relics along the western axis. Entry and egress was provided for the western crypt by a set of stairs. This church was more

clearly focalized and organized than its predecessor.

Efficient organization was also the theme of the Carolingian texts

concerning Agaune. Consider the so-called foundation charter of

Sigismund. Theurillat has argued plausibly that this source was forged

whole cloth in the late eighth or early ninth century. 45It is of rather

little value for the sixth century, but

no one has yet bothered to put

it into its Carolingian context. It is

worthwhile to make the attempt

here.

The text falls into two parts: first is the account of a huge council purportedly taking place at Agaune in 515 consisting of 40 bishops, 40 counts, and a very pliant `King' Sigismund; second is the

king's donation charter, which focuses on the royal properties

given

Blondel spoke of a crypt in the

eastern apse as well, but Lehner, "Saint

Maurice", observed no evidence for this.

" Theurillat, L'Abbayýede St-Alaurice dAgaune,

p. 63. Dubuis and Lugon, "Les premiers siecles d'un diocese alpin", pp. 128-9, cite an alternative date: during the

reign of Rudolf III of Burgundy (993-1032).

286

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

dialogue

between

is

The

as

a

presented

council

to the monastery.

bishops and king. The counts are there only for show. Four bishVictor, and Viventiolus. HistoriTheodore,

Maximus,

dominate:

ops

long

dead

by

Theodore

impossible:

is

the

time

was

this

utterly

cally,

The

it

is

Rhetorically,

tone

Sigismund.

the

effective.

of

extremely

of

king

Arian

from

is

the

the

the

abjures

start when

set

proceedings

heresy and asks the bishops to instruct him in the true religion. The

four do not hesitate to do so. After evoking some general principles

(for example, to live justly), Theodore gets down to brass tacks. The

immediate and pressing question is what to do about the bodies of

for

Unmentioned,

build

Who

them?

Theban

churches

will

the

martyrs.

had

been

built

for

know

is

those relics

that

the

we

church

of course,

The

king

do

by

to

of

monks.

volunteers

tended

a

group

what

and

is necessary. Theodore advises him on how to dispose of the relics:

be

Maurice

that

the

can

with

a

specific

associated

name

ones

put

himself, Fxupery, Candidus, Victor - in an ambitus of the basilica

(this is, surely, a reference to the wall of the Carolingian church in

in

is

the

the

put

others

and

a well-fortified place

arcosolium)

which

Then

have

be

the monks there carry on

they

that

stolen.

cannot

so

day

and night.

psalmody

perpetual

an office of

The latter is institutionalized through the prescriptions of Bishops

Victor and Viventiolus. There are to be eight groups - here they

for

`monastic

(a

in

term

community'),

are called normae common

most

of the other sources of the period, turmae- to succeed one another

in relay for the various hourly offices. An abbot presides over all;

`deacons' preside over each norma. The monks are freed from manual labor; their clothing, drink, and food are prescribed. They are

to sleep in one dormitory, cat in one refectory, warm themselves in

the same warming room.

The king's role, says the Viventiolus of this account, is to endow

the monastery. If the abbot runs into any problems, he is to betake

himself to the Holy See and seek help there. This is an extraordinary

`right

such

suggestion:

of appeal' was a provision of only the rarest

and most up-to-date privileges of the eighth century, such as the one

Stephen II gave Fulrad of Saint-Denis in 757. }6 It is so unusual that

46 P. Jaffe et al. eds., Regesta Pontficunt Rontanorunt, 2 vols. (2nd ed., Leipzig,

1885-88; reprint Graz, 1956), n° 2331. There are two versions, of which the first,

A, is largely authentic. See A. Stoclet, "Pulrad de Saint-Denis (v. 710-784), abbe

l byen Age 88 (1982), pp. 205-35.

Le

`exempts"',

de

monasteres

et archipretre

SAINT-TIAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

287

it suggests that the creation of the `foundation charter'

of Sigismund

might reasonably be placed at the time of Fulrad. Indeed, we know

from the Liber Pontjcalis that Agaune is where Stephen

and Fulrad

met in 753, on Stephen's trans-alpine journey to ask for Pippin's aid

against the Lombards.?

However, there is another context for the text as well,

one that

is broader and may be more important: the monastic

reform movement of the Carolingian period. Three decades ago Francois Masai

already noticed that the foundation charter of Sigismund echoed two

rules. 8 One, the so-called `Rule of Four Fathers', has Serapion, Paphnutius, and two fathers both named Macarius together in council,

each taking turns in a sort of dialogue in which they dictate their

rule. The other is the Rule of St Benedict. Both were collected in

the Carolingian reformer Benedict of Aniane's Codex Regularum.`}0It

is clear, however, that a monastic reformer

have

need not necessarily

been at Aachen or Inden to have been preoccupied with cleaning

up untidy monastic practices and making all orderly, regular, and

uniform. Indeed, it is rather likely that Agaune was the place where

the foundation charter of Sigismund was drawn up.

Although the tunnae of the monks at Agaune were mentioned in

Dagobert's charter for Saint-Denis in 654, in the

phrase `psallencius

per turmas', this use of the term remained an isolated instance until the

Carolingian period. 50 None of the sources that may be associated

with the foundation of 515 - not the writings of Avitus of Vienne,

not the Pita abbalum Acaunensium,not the additions made after the

death of Sigismund to the text of the PassioAcaunenzsium

martyrum, not

the writings of Gregory of Tours nor even the later chronicle of

Fredegar - say a word about tunnae. These sources certainly stress

the day and night psalmody carried out by the monks; but they are

By contrast, the

unconcerned about its practical organization.

Carolingian sources can almost be so identified becauseof their

use

" Liber Pont calis, c. 94, §24 in: L. Duchesne

ed., Le Liber Ponti icalis. Texte, introduction et commentaire,2 vols. (1886-92), 1,

p. 447.

98 Masai, "La Vita patnan iurensium",

pp. 51-3.

{° Benedict of Aniane, Codex

regularum, part 1,1vIigne PL 103, coll. 435-42 for

the Rule of the Four, the Benedictine rule is not printed in sequence in the PL

ed.

but it constituted the first \'Vestern Rule in Benedict

of Aniane's collection. The

most recent cd. of the Regula IV Patrum is J. Neufville, "Regle des IV Peres et

Seconde Regle des Peres. Texte

critique", Revue benedictine77 (1967), pp. 47-106.

so ChLA 13, p. 37, n° 558.

288

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

Century',

Ninth

`Chronicle

In

the

the

the

term.

of

so-called

of the

"

In

in

turmae

to

their

the

chant

psalms.

nine

monks are organized

Vita Sadalbergae,Sadalberga's nuns are distributed `per turmas, ad instar

52In the Carolingian GestaDagobertiI, Dagobert's reform

Agaunensium'.

(in

Agaune

Tours

Saint-Denis,

this

the

case)

and

model of

as

on

of

53

And

in

Vita

has

turmatim.

the

the

the

psalms

chanting

monks

well,

Amati, which, however, may possibly be a Merovingian text, the saint

`per

Remiremont

house

his

septemturmas', presumably

at

organizes

inspired by Agaune, where he had once spent time as a monk. 54

When a donor named Ayroenus gave a donation to the monastery

`to

he

did

indeed

in

765,

Saint-Maurice

the

so

sacred

place

or

of

Matulphus,

Valdensis,

the turmarius, is

the

turma

monk

to the

where

interpreted

55

have

`vestige'

Historians

this

to

as

a

preside'.

of

seen

the original organization at Agaune; but it might as easily mark a

newly reformed organization there.

More than mere interest in organization may be involved. The

56

In

Eucherius's

had

Passio

turma

military

associations.

primarily

word

`squadrons'

impious

Theban

the

the

who carried out

martyrs,

of

emperor Maximian's evil persecutions were organized in turmae.57 In

Si For the text, see Theurillat, L'Abbaye de Stillaurice d'Agaune, p. 55.

52 Vita Sadalbergae,c. 17, B. Krusch ed., MGH SRAM 5 (Hannover, 1910), p. 59.

53 GestaDagoberti I reis francorum, c. 35, B. Krusch ed., MGH SRAM 2 (Hannover,

1888), p. 414.

" Vita Amati, c. 10, B. Krusch ed., MGH SRAM 4 (Hannover, 1902), p. 218. On

the possibility of this as a Merovingian text, see: I. N. Wood, "Forgery in Merovingian

hagiography", in: Fälschungenint rllittelalter. Internationaler Kongressder HIGH, tlliinchert,

16. -19. September1986, Pt. 5: FingierteBriefe, Frönunigkeitand Fälschung Realienfälschungen,

MGH Schriften 33. V (Hannover, 1988), pp. 370-1.

55 M. Besson, "La donation d'Ayroenus ä Saint-Maurice (mardi 8 octobre 765)"

d'histoire ecclesiastiquesuisse 3 (1909),

zeitschrih fur schweizerischeIi rchengeschichte/Revue

,

294-6.

pp.

se The Vulgate provides a quick overview of tunna's semantic field. In Gen. 32: 7-8,

Jacob divides his people and herds into duae turmae. They are his `company', to be

is

decidedly

but

that

one

unarmed. In Exod. 6: 26, God commands Moses

sure,

and Aaron to lead the children of Israel out of Egypt `per turntas suas'. Here turma

is used in place of cognatio.Nevertheless here we are not far from military meaning, for these same cohorts will (in Num 1:52) pitch their camp per turrnas et cuneos

Chron.

In

I

is

27

king's

the

suum.

army

organized in turmae in comexercilum

atque

Nevertheless,

in

Chron.

2

35: 10 the Levites stand in turntis to

2400

men.

of

panics

take part in the rites of Passover. Clearly the meaning of turnta deserves special

here adduced, we may say fairly certainly that it

but

from

the

evidence

study;

implies more than a simple `group': it is an organized band, under a leader, and,

it can quickly become so.

armed,

not

necessarily

while

51 Eueherius, Passio AcaunensiumMartyrum, c. 1, p. 33.

SAINT-DIAURICE

D'AGAUNE

AS A PLACE

OF POWER

289

Avitus of Vienne's poem on the deeds of the Jews, the

word is equivalent to an army cohort. 58 In Prudentius's Psychomachiathe virtues

are drawn up in turmae.59 In Gregory's Moralia in Job the Chaldaean

army forms three turmae.60

Using the word turma thus gave a particularly militant cast to the

efficacy and singleness of purpose of monastic psalmody. In the

Carolingian period it became a kind of shorthand for the

monastic

corporation as a whole: Lorsch was a monachorumturma in a charter

of protection issued by Charlemagne c. 772/3, and Fulda's abbot

Sturm presided over turmae monachorumin a charter of 779. G1It is

useful to note in this regard that visual representations of the soldier-martyr Saint-Maurice began to be produced only in the ninth

century. fi2 In the Passio Sigismundi regis, the king sets up his choirs of

psalm-singers at Agaune `ad irutar caelestisrnilitiae'.63 Monasteries had

always been understood as a kind of religious army, but in the

Carolingian period the liturgy itself was militarized. This may be

connected with its renewed emphasis on prayer for the dead. "

Via a rapprochement of material and written sources, we have

seen that Agaune was a powerful holy place - in part meaning a

model holy place - for a very long time. The king, his bishops,

and the military martyrs they honored there were always paramount

in the power that it exerted. What is more interesting is that those

elements were paired with different ones, hence given different meanings, at different times. In 515 and shortly thereafter, they were tied

58 Avitus, Poematumlibri VI, bk. V, in: Chevalier, Oeuvres

completes,p. 78: `Post quos

belliferae disponunt anna cohortes,

/Ducunt et validas instructo robore tunas'.

59 E. g. Prudentius, Pss'chornachia,1.14, J. Bergman

ed., CSEL 61 (Wien, 1926),

p. 170: `ipse salutiferas obsessoin corporetumors depugnareiubes'.

6o Gregory I, Aloralia in Job, II, c. 15, Al. Adriaen

cd., CCSL 143 (Turnhout,

1979), p. 75.

G1MGH DD 1, p. 105, n° 72 (Lorsch);

p. 177, n° 127 (Fulda).

62 D. Thurre, "Culte et iconographic de

saint Maurice d'Agaune: bilan jusqu'au

XIII` siecle", Zeitschri l filr schweizerischeArchaeologie

and Kunslgeschichte/Revue

suisse d'art

et d'archaeologie/ Rivista sviuera d'arte e d'archeologia49 (1992), pp. 7-18.

63 Passio Sigimiundi regis,

c. 6, B. Krusch ed., MGH SI1vI 2 (Hannover, 1888),

p. 336.

6+ On Carolingian prayer for the dead,

see: M. Lauwers, La mernoiredes anceires,

le souci des morts. Aloris, rites et societe

au mojen age (diocesede Liege, XI`--XIII` siecles)

(Paris, 1997), pp. 94-100. The writings

of Gregory the Great already expressed

some themes, especially regarding the efficacy of prayer for the dead, that were

later picked up by the Carolingians. On Gregory's

views, see: J. Ntedika, L'evocation

de Pau-delä dans la priere pour les morts. Etude de patristique

et de liturgie latines (IV-VIII`

siecles)(Louvain, 1971), pp. 59-60,105-10.

290

BARBARA

H.

ROSENWEIN

innovation.

In

liturgical

the midto an emphasis on episcopal

from

freedom

they

of

episcopal

suggested a model

seventh century,

harnessed

ideal

In

to

they

an

the

were

early ninth century

control.

liturgy.

militant

of organization and

These were not contradictory representations: episcopal will and

freedom from episcopal control went hand in hand in the miditself

by

liturgy

tunnae

a reflection of episcowas

seventh century, and

There

is

every reason

pal creativity and royal and soldierly militancy.

facets

Agaune

from

level

these

coexisted

at

think

that

all

to

at some

Nevertheless,

in

515.

its

the reason that

time

the

reorganization

of

it is important to tease out various emphases and subtleties of meaning is to quell our impulse to generalize. If we read that a monastery

Agaune,

jump

`on

to the

the

of

we

should

not

model'

was set up

`laus

(Indeed,

perennis'.

the

that

monastery

carried

out

such a

conclusion

) If we are speakit most certainly did not carry out `the' laus perennis.

ing about a mid-seventh century monastery, it is very much more

likely that the place had an episcopal exemption - or wanted one.

If our source is from the late eighth century, the monastery in question was probably organized by turnzaeand performed an aggressive

hoped

least

do

liturgy

to

or

at

so.

non-stop

All this leads to a final, general hypothesis. It is that for a place

have

it

be

lasting,

the same sort of complexity as

to

must

of power

a great piece of music, so that in each era new maestri can tease out

different timbres and themes. So it was with Agaune in the early

middle ages.