PCPFlexibility - Health Care Compliance Association

advertisement

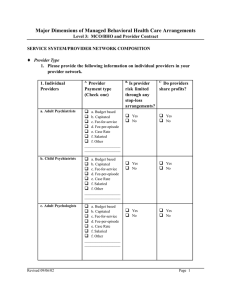

Primary Care Provider Contracting Flexibility: The Bane of the Compliance Officer? It’s probably just the normal aging process (I prefer the term “maturing”), but I often I catch myself reflecting on the fact that life in general, and certainly business life , is getting more complex and less predictable. A prime example can be found in our own industry. In the past, if a managed care organization was described as a “direct contract model HMO,” it was highly likely that its primary care physicians (PCPs) were capitated; that is, compensated on a prepaid, per-member-per-month basis. The underlying assumption was capitation was more consistent with the goal of controlling costs by avoiding unnecessary care (“overutilization”). As the managed health care business has matured, however, we are seeing more variations in physician contracting practices. While many PCPs are still paid straight capitation, others now have fee-for-service contracts and some get a combination of capitation and fee-for-service payments and additional compensation for designated services or procedures. There are a number of reasons for these changes. Because a capitated physician is not submitting claims for payment for each visit or procedure, one of the challenges of health plan management is to ensure that the doctor is conscientious about submitting encounter data (records of visits and treatment) that the plan needs to track the delivery of care and to report to its governmental contracting entity or accreditation organization. A common solution is to pay the physician a fee for each encounter form submitted. Special payment provisions also may be used to influence physician behavior in other ways , to encourage providers to adhere to certain treatment protocols or encourage certain types of visits or procedures (well-child visits, or immunizations) that the plan wants to promote. Finally, physicians are often paid additional fees for lab tests or other procedures performed in their offices. Each of these variations in payment arrangements, and others not detailed here, serve legitimate business purposes, and many have the laudable goal of improving care to the member. However, they also have an unintended and often unexpected result: complication of the compliance and fraud and abuse detection functions. From a business standpoint, the terms “entrepreneurial”, “flexible”, “tailored” and “results oriented” are positive ways of addressing an issue. When applied to PCP contracting, however, they can present difficulty for the Compliance Officer fraud and abuse investigator. From our standpoint, we prefer “consistent”, “uniform”, “standard” payment arrangements -- and it’s easy to understand why. The very nature of a compliance or audit function lends itself to looking for exceptions to the required or expected process or pattern. Consider the following as an illustration of my point. In analyzing encounter data you notice a pediatrician is reporting an unusually high number of preventive health visits compared to other physicians in the same geographic area. Reviewing this data with the assumption he is a capitated provider (and hence has no financial incentive to provide more than the required level of care) may paint the picture of a very conscientious and effective physician. Indeed, in a capitated payment arrangement, a primary concern of utilization review is to identify indications of underutilization. On the other hand, if you assume the provider has a fee-for-service contract, particularly one with an enhanced payment arrangement for well-child visits and for additional lab tests performed in his office, you may wonder if he is providing unnecessary and excessive care, or worse, simply billing for care not rendered at all. As compliance programs and special investigation units increase the use of “data mining” (computerized analyses of claims and utilization data) to identify patterns that fall outside the norm, it is critical that that these variations in payment arrangements be known and understood beforehand, and are considered in making inquiries and assessing results. Otherwise, you may find you have analyses that are not useful and can even be misleading. And that’s a trap that Compliance Officers of any age want to avoid.