waste management inc. strategic case analysi ss

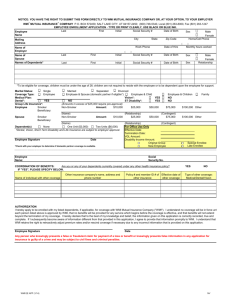

advertisement