Running head: THIS IS A SHORT (50 CHARACTERS OR LESS

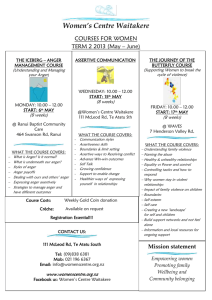

advertisement