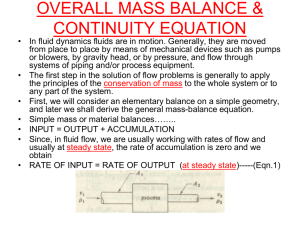

flow and level measurement

advertisement