Barriers to Entry

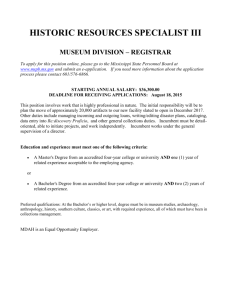

advertisement