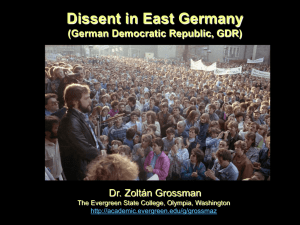

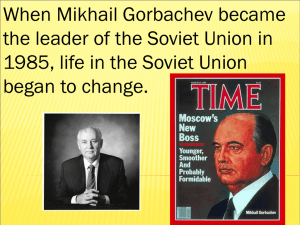

The Fall of the Wall: The Unintended Self

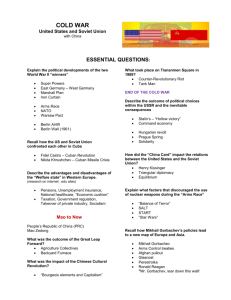

advertisement