English - Freedom from Hunger

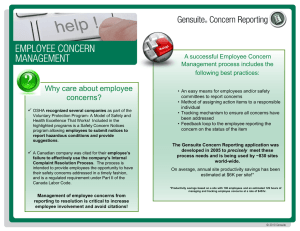

advertisement