REMEMBERING THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN SOUTH AFRICAN

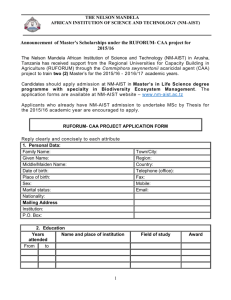

advertisement