Reflections on Affective Events Theory : The Effect of Affect in

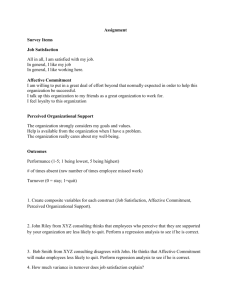

advertisement

REFLECTIONS ON AFFECTIVE EVENTS THEORY Howard M. Weiss and Daniel J. Beal ABSTRACT In the few years since the appearance of Affective Events Theory (AET), organizational research on emotions has continued its accelerating pace and incorporated many elements of the macrostructure suggested by AET. In this chapter we reflect upon the original intentions of AET, review the literature that has spoken most directly to these intentions, and discuss where we should go from here. Throughout, we emphasize that AET represented not a testable theory, but rather a different paradigm for studying affect at work. Our review reveals an obvious shift toward AET in the way organizational researchers study affect at work, but also that some elements have been neglected. Ultimately, we see the most fruitful research coming from further delineation of the underlying processes implicated by the macrostructure of AET. INTRODUCTION In their chapter in this volume, Ashton-James and Ashkanasy state that ‘‘since its publication in 1996, Affective Events Theory (AET) has come to be regarded as the seminal explanation of the role that affect plays in The Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings Research on Emotion in Organizations, Volume 1, 1–21 Copyright r 2005 by Elsevier Ltd. All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1746-9791/doi:10.1016/S1746-9791(05)01101-6 1 2 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL shaping the attitudes and behaviors of employees in the workplace.’’ As flattering as that characterization is, and as frequently as Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) has been cited since it appeared, we think that to a large extent the statement misrepresents the place of AET in the recent history of workplace emotion research. We say this for a few reasons. To begin with, significant empirical and theoretical papers on workplace emotions had appeared before the publication of AET. Fineman (1993), Ashforth and Humphrey (1995), and Pekrun and Frese (1992) had already published important conceptual pieces advocating more focused attention to emotional experiences at work. George (1989, 1990, 1991) had already published a number of important empirical studies on moods at work. Burke, Brief, George, Roberson, and Webster (1989) had already developed and published a work-focused modification of the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) that they were using with interesting results. If you conducted an interrupted time series analysis with the publication of AET as the interruption you might, perhaps, see an increase attributable to AET, but the dominating visual would be an upward trend in research on emotions. Of course, influence can be gauged in ways other than the sheer number of studies conducted on a topic. Ashton-James and Ashkanasy regard AET as the ‘‘seminal explanation’’ of affective experiences at work. Again flattering, but ‘‘explanation’’ implies a burden that, frankly, AET was never designed to carry. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) explicitly stated that they offered AET as a roadmap for future research. The intent was to integrate what was then known about basic research on emotions into an organizing framework to help identify key issues and directions for the study of emotions in the workplace. AET presented a ‘‘macrostructure’’ for understanding emotions in the workplace. The expectation was that the macrostructure would help guide research so that, over time, its ‘‘arrows’’ could be replaced with process explanations. Micro-structures would develop out of focused research. ‘‘Explanation’’ was yet to come. Certainly, some testable hypotheses were embedded in the explication of AET. However, we believe that the more interesting elements of AET could be found in the suggested directions for research, the underlying assumptions of the model, and the more general perspective that ties the assumptions together. We also believe that the general perspective embodied in AET speaks more broadly to the existing paradigm of organizational research. Consequently, the influence of Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) can best be judged by how well the research on emotions has been influenced by the perspective, assumptions and suggested directions offered in the presentation of AET. Therefore, in the next section we briefly revisit some Reflections on Affective Events Theory 3 of the main assumptions of AET and the research directions it advocated. These then will help us evaluate the influence of AET on the exiting literature. ASSUMPTIONS AND RESEARCH SUGGESTIONS OF AET Satisfaction is not Emotion Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), before it was written, was originally intended to be a paper about job satisfaction. More specifically, the paper was intended to show that the traditional paradigm of satisfaction research was missing an important experiential component, a component having to do with the subjective, fluctuating experience of emotions. As the paper developed, that original emphasis changed from a critique of job satisfaction research to a presentation of a framework for studying emotions. Later, Weiss (2002) wrote a paper more consistent with the original objectives of Weiss and Cropanzano. The original intent of the 1996 paper is apparent in its initial few pages. There a summary of the existing paradigm of satisfaction research is presented and used as a point of contrast to the assumptions of AET. In those same pages Weiss and Cropanzano tried to articulate the differences between the construct of satisfaction as evaluative judgment and true affective states like moods and emotions. Today this distinction is well understood, but at that time definitions of job satisfaction as emotion predominated. Weiss and Cropanzano offered a definition of job satisfaction as an evaluative judgment about one’s job, different from but influenced by the emotional experiences one has on one’s job. A number of research directions offered by AET turn on this distinction. Suggesting that emotional experiences influence satisfaction judgments begs the question of how this occurs. Some of the initial research influenced by AET was conducted to demonstrate that on-line affective experiences influence satisfaction, but the processes still remain unexplored. Another distinction made in AET, that between affect driven behaviors and judgment driven behaviors, is a direct outgrowth of the affect-satisfaction distinction. This distinction in outcome types, in turn, raises at least two research questions. The first has to do with the processes by which affective states influence behavior unmediated by satisfaction. The second relates to the conceptual explication of which types of behavior fall in to each category. 4 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL Events are the Proximal Causes of Emotions AET makes a clear distinction between features and events as explanatory constructs and one of the central theses of AET is that events are the proximal causes of affective reactions. Things happen to people at work and often their reactions are emotional in nature. The basic literature on emotions consensually accepts the idea that events drive changes in emotional states. There may be differences of opinion as to how events are interpreted, the relative impact of positive and negative events, the filtering process of personality, etc., but events are instigators of changes in emotional states. On the other hand, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) noted that existing research on work satisfaction and affect focused on the relationships between features of the environment and affective criteria. They argued that using features to predict affect represented a mismatch of construct types. Affect, being a state, requires causal explanations that emphasize changing circumstances. Hence the focus on events. Environmental features, being relatively stable, are unable to explain change. Knowing that a work setting has good promotion opportunities cannot, by itself, explain why a worker is happy at one moment but not at the next. AET drew a connection between work events and emotional reactions but this connection was just a place-holder for processes of affect instigation. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), of course, described the existing literature on appraisal theories of emotion, suggesting that these theories offered guidance for the processes involved. They also suggested that one way in which personality enters into the picture is by influencing reactions to events. (A more detailed discussion of these processes can be found in Weiss & Kurek, 2003). Clearly, a key objective of AET was to encourage researchers to think about events as proximal causes of emotions and other work phenomena. Overall, AET intended for researchers to give greater attention to events, their interpretation, their structure, their informational value, etc. While AET naturally focused on work events, even a cursory reading of the theory would make apparent the rather obvious idea that both job related and nonjob related events can instigate emotional states at work and, therefore, have work consequences. Affect Driven Versus Judgment Driven Behaviors By 1996, numerous reviews and meta-analyses had consistently shown that job satisfaction shows negligible relations with job performance. Consequently, organizational psychologists, traditionally confusing satisfaction Reflections on Affective Events Theory 5 and affect, were hard pressed to acknowledge that affect had much to do with performance. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) argued that differentiating the constructs of affect (mood and emotions) from satisfaction (evaluative judgment) could add more precision to an understanding of how affect influenced performance. In so doing, they made the distinction between affect driven work behaviors and judgment driven work behaviors. Affect driven behaviors are those behaviors, decisions, and judgments that have (relatively) immediate consequences of being in particular affective states. Affective states are the proximal causes of these behaviors, and, as such, they are temporally coincident with those states and consequently are time bound. Judgment driven behaviors are those behaviors, decisions, or judgments that are driven by more enduring attitudes about the job or organization. Evaluative judgments, or attitudes, are the proximal causes of these behaviors. In the AET macrostructure, true affective states do have important performance implications but they are relatively immediate, transient, and variable within-persons over time. Although they offered examples to illustrate the differences between these two types of behaviors, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) did not offer a system to classify work outcomes as affect or judgment driven. The Ebb and Flow of Affective Experiences Noting that states, affective or otherwise, vary over time, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) argued that affect researchers had to take change in moods and emotions over time seriously. For satisfaction researchers, time was of little relevance. Of course satisfaction could change but it was not conceptualized as a state like variable and, therefore, its changeability over the course of time was not of central interest. Emotions and moods are states and states have definite beginnings and endings. Their patterns of change over time are fundamental to their study. As a consequence, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) explicitly called for more within-person research on fluctuations in emotional states. This was particularly important, they argued, when examining affectperformance relationships. Transient affective states have immediate, and transient performance consequences, and thus the study of affect-performance relationships required dynamic within-person methods. Phenomenal Structure of Affect At the time that Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) was published, research on the organizational consequences of mood predominated over research on 6 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL discrete emotions. Weiss and Cropanzano called for more emphasis on the causes and consequences of discrete emotional states. Again, using satisfaction research as a point of contrast, they noted that much work had been done on the dimensional structure of satisfaction (i.e., facets of job satisfaction) while the structure of affective reactions had, to that point, been neglected. One lengthy section of the paper discussed the appraisal processes that influenced the experience of particular emotions while another discussed how discrete emotional experiences influence work behaviors. The emphasis on studying discrete emotions was consistent with the overall call for a more ‘‘experiential’’ focus for organizational psychology generally. Episodic Structure to Organizational Experience Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), borrowing heavily from Frijda (1993), discussed the episodic structure of emotional experiences, with an emotion episode comprising a series of emotional states extended over time and coherently organized around an underlying theme. During the episode, discrete emotions may vary but the person remains in a heightened state of emotional engagement. What was implied but not explicitly stated was an interest in studying episodic structures to life experiences generally. Here we are talking about the subjective beginnings and endings to states and activities. The assumption was that life, not just emotional life, is structured episodically. The Broader Perspective As we have said, the way to gauge the influence of AET is not by counting the references to the paper, and certainly not by looking at the enormous growth in research on emotional experiences at work. Instead, the impact can better be assessed by delineating the basic assumptions and research suggestions, and then examining how these assumptions and suggestions have been developed in the years after the publication of Weiss and Cropanzano (1996). We have revisited these assumptions and suggested directions and in the next section will use them to organize our review of papers citing AET. However, we think it is important to state that there was an overriding logic or perspective to AET that went beyond the specific assumptions. In fact, this overriding perspective went beyond the study of emotions. In this way AET was only partly about emotions. It was about breaking old paradigms and developing new ones. The old paradigm was certainly Reflections on Affective Events Theory 7 exemplified by the job satisfaction literature but was not limited to that literature. It was (and is) characterized by examining relations among stable properties of different entities, whether those entities are people, work groups, or organizations. So, performance and satisfaction, as properties of people are associated with climate, or reward structures or cohesiveness, as properties of organizations or groups. Even constructs that vary meaningfully over time, like performance or affect, are ‘‘dispositionalized’’ to study in the between entities paradigm that prevails. Meaningful within-person variance is treated as error. Between subjects analyses predominate. In contrast, AET was intended to encourage looking at within-person variability. It was intended to focus on the things that happen to people, rather than the features of the work environment. It was intended to encourage organizational researchers to pay closer attention to the way work is experienced, the way time is psychologically structured, the way life naturally ebbs and flows at work. We will see whether and to what extent these changes along these lines have occurred. RESEARCH RELEVANT TO AET Since the appearance of Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), many studies have appeared that speak to the role of affective events in organizations. Some of these studies have explicitly tested aspects of the macrostructure laid out in AET; others have not referred to specific elements of the macrostructure, but have used AET as a framework for guiding their research efforts; still others make no reference to AET but nevertheless have examined elements of the macro-structure or fit generally within the paradigm suggested by AET. Obviously, space limitations prevent us from presenting a comprehensive examination of all types of studies examining all aspects of AET. Therefore, we will limit our discussion to those studies that have had the most relevance to the paradigmatic elements discussed in the previous section. Satisfaction is not Emotion Despite the fact that this idea provided the impetus for AET, relatively few studies have examined it directly. Weiss, Nicholas, and Daus (1999) offered particularly compelling evidence for treating job satisfaction as an overall attitude that is influenced by both affective experiences and job beliefs. A sample of managers completed measures of dispositional happiness, cognitions concerning their jobs, and overall job satisfaction. In addition, 8 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL they reported their affective experiences four times a day for a 16-day period. Of particular importance for differentiating the roles of affect and beliefs, affective experiences aggregated over the 16-day period held a strong relation to overall job satisfaction and this effect was independent of both dispositional happiness and beliefs concerning the job. Consistent with this analysis, Fisher (2000) found that measures of positive and negative affect taken throughout the day were independently related to overall measures of job satisfaction, but were not identical to it. Fisher concluded that affect at work was part of the overall job satisfaction attitude, but distinct enough to merit research apart from job satisfaction. Similarly, Fisher (2002) again found significant zero-order relations of positive and negative affect to overall job satisfaction. Interestingly, however, when simultaneously considering a variety of other factors, the relations of affect to job satisfaction were reduced to non-significant levels; however, positive and negative affect did maintain relations with other hypothesized variables, including variables important for organizations such as affective commitment, helping behavior, and role conflict. More recently, Ilies and Judge (2002), (Judge & Ilies, 2004) have also examined the separation of affect and job satisfaction. In these studies affective experiences as well as job satisfaction were measured multiple times per day over several weeks. When job satisfaction was measured in this manner, affective experiences again obtained moderate to strong relations to job satisfaction, but were clearly not equivalent constructs. Finally, Fuller et al. (2003) examined daily mood and job satisfaction as they fluctuated over the course of a 70–90-day period. Again, these researchers noted a likely causal effect of daily mood on both concurrent satisfaction and nextday satisfaction. Thus, as Weiss (2002) has argued, much like any other attitude object, job satisfaction is an overall evaluation of one’s job and this evaluation is made by considering both affective experiences and beliefs relevant to the object. Despite the relatively few studies that have explicitly examined the similarities and differences between job affect and job satisfaction, it appears that two overall points have been made abundantly clear: job satisfaction does not capture affective experiences and affective experiences help determine the overall attitude. Events are the Proximal Causes of Emotion In contrast to the scarcity of studies that explicitly differentiate between affective experiences at work and job satisfaction, many studies have Reflections on Affective Events Theory 9 examined the idea that events are the most proximal causes of affective experiences. For example, the Fuller et al. (2003) study examined the influence of stressful work events on concurrent and future levels of strain and job satisfaction. Using sophisticated time series models, these authors found evidence not only that events had causal precedence on both strain and satisfaction, but also that strain mediated the effect of stressful events on later job satisfaction. A more qualitative examination of events by Grandey, Tam, and Brauburger (2002) revealed that incidents of interpersonal mistreatment from customers was the most frequently cited cause of anger in a sample of part-time employees. Paterson and Cary (2002) examined the impact of a single major event on affect: downsizing within the organization. These authors found that such an event held strong relations to feelings of anxiety. Of note is that these authors helped to expand the connection between events and affective reactions by specifying relevant appraisals and perceptions of organizational justice as precursors to anxiety. The connections between a single event, appraisals of justice conditions, and affective reactions were also examined in a laboratory study by Weiss, Suckow, and Cropanzano (1999). These authors had participants play a game that was set up to create various justice conditions. By creating events that varied in their levels of procedural and distributive justice, Weiss and colleagues predicted and found specific emotional reactions that included happiness in response to positive outcomes, guilt in response to positive outcomes with a favorable procedural bias, anger in response to negative outcomes and an unfavorable procedural bias, and pride in response to positive outcomes, regardless of the bias in procedures. Organizational justice, it appears, is frequently examined within an affective events framework. In another example, Wiesenfeld, Brockner, and Martin (1999) examined the affective reactions of people who witnessed another person being laid off in either a fair or unfair manner. These authors noted that witnessing such an event had a greater effect on self-conscious negative emotions such as guilt and shame than on other negative emotions. Finally, Schaubroeck and Lam (2004) focused their attention on envy and injustice in response to the specific event of being passed over for promotion. Not too surprisingly, expecting a promotion and being rejected led to feelings of envy toward the promoted co-worker, but these reactions were moderated by one’s perceived similarity to the co-worker. Furthermore, envy was strongly related to feelings of injustice and led those who were rejected to like the promoted co-worker less than before the promotion and to perform better after being rejected. 10 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL Another theme that is noticeable in studies that examine events is that most often, researchers emphasize reactions to negative events. For example, Ayoko, Callan, and Härtel (2003) examined employees’ experiences of being bullied at work, their emotional reactions to bullying, and incidences of counterproductive work behavior. Bullying was related to specific emotional reactions and both were in turn related to counterproductive work behavior. In addition, the relation between bullying and counterproductive behavior was reduced once emotional reactions were entered into the equation, supporting the mediational role of affective experiences. In another example of negative work events, Conway and Briner (2002) examined breeches in psychological contracts held between employees and organizations. They found that such events occur with relative frequency, and are linked both to negative mood on days when breeches occur as well as specific negative emotions immediately following the breech event. In contrast to the tendency to focus on the negative, these authors also examined the positive event of exceeding the promises that were made by the organization. Exceeded promises were related to increased feelings of self-worth, and this relation increased as the importance of the promise increased. The studies reviewed above demonstrate three important points. First, organizational researchers have embraced the role of events both as proximal causes of affective experiences and as important predictors of organizationally relevant outcomes. In most cases where the appropriate variables were included, affective reactions mediated the connection between events and outcomes, providing support for one of the main predictions of AET. A second important point concerning research from an events perspective is that the variety of events is impressive. There does appear to be an emphasis on negative events, but considering that our experience of emotions is much more differentiated when the experiences are negative (Averill, 1980), this is probably not too surprising. Indeed, a study reported by O’Shea, Ashkanasy, and Gallois (2002), which did examine the impact of both positive and negative events on affect and attitudes, found greater support for the mediational status of affect for negative as opposed to positive events. Perhaps, then, the emphasis on negative events reflects not the neuroticism of our field, but rather the stronger influence of negative events in our lives (cf. Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001). The third important point from an events perspective is that this literature is informing not just our understanding of emotions in organizations, but also of other important areas of research including organizational justice, psychological contracts, and work stress and strain. Reflections on Affective Events Theory 11 Affect Driven Versus Judgment Driven Behaviors In discussing AET, many authors have cited the key distinction between affect driven behaviors and judgment driven behaviors. Too often, however, this discussion leads to an empirical study that focuses on only one type of behavior over another. Rarely have empirical studies assessed both affect driven and judgment driven behaviors together to determine if affective reactions relate differentially to the behaviors. Two counter examples of this trend are noteworthy. Lee and Allen (2002) examined job affect and job cognitions and their relations to Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs). They reasoned that OCBs directed at individuals (OCBI) would be more representative of affect driven behavior, whereas OCBs directed at the organization (OCBO) would rely more on stable attitudes and, therefore, would be closer to judgment driven behavior. Results supported the importance of cognitions in predicting OCBO over job affect, and the reverse pattern was found for OCBI. Although the latter finding was not as strong as the former, the use of global measures of overall job affect as opposed to more experiential assessments of affect could easily account for this. In another recent study, LeBreton, Binning, Adorno, and Melcher (2004) examined the relative importance of several variables in predicting overall judgments of negative job behaviors (e.g., ‘‘I make joking or sarcastic comments about my job.’’) as well as reports of absenteeism. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) used absenteeism as a specific example of an affect driven behavior. Supporting this proposition, cognitive and dispositional variables were more important in the prediction of overall negative job behaviors, whereas job affect was more important in the prediction of absenteeism. Although these studies are generally supportive of the role of affective experience in predicting affect driven and judgment drive behavior, definitive empirical support has not yet appeared in the literature. The Ebb and Flow of Affective Experiences As mentioned above, AET called for a more focused examination of the changing nature of affective experiences. Implicit in this focus was the need to examine within-person variation – not just in affective states – but also in other antecedents and consequences of affect. A brief examination of the organizational literature reveals that this call for a paradigm shift has fared well. Many of the studies that have investigated the macrostructure of AET have focused on within-person changes in affective states and have 12 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL emphasized how an examination of within-person variability can result in different conclusions compared to differences at the between-person level (e.g., Conway & Briner, 2002; Fisher, 2000; Fuller et al., 2003; Ilies & Judge, 2002; Totterdell & Holman, 2003; Weiss et al., 1999). For example, Fisher (2003) investigated lay conceptions of the happyproductive worker thesis. Most previous examinations of this idea have been concerned with whether a generally happy person performs better than a less generally happy person. The within-person version of this idea, however, is that a person is more likely to perform better when he or she is happy than when he or she is less happy. Although endorsements of these different ideas varied greatly in Fisher’s samples, the empirical data supported the notion that, at least for self-report data, there is a stronger within-person relation between affect and performance than there is at the between-person level. Also worthy of note was that when variance was partitioned to withinperson and between-person pools, the within-portion of the affect variance was 59% of the total, and the within-person variation of performance was 77% of the total. So, not only are the relations stronger at the within-person level, they also represent a substantially larger portion of the overall variation in performance. These findings are consistent with several recent calls for increased attention to within-person variation in all manner of organizational constructs (Beal & Weiss, 2003; Beal, Weiss, Barros, & MacDermid, in press). Further evidence of the success of a within-person perspective comes from a recent study by Zohar, Tzischinski, and Epstein (2003). These authors assessed the daily experiences of a sample of medical residents over five three-day periods. Focusing specifically on affective and fatigue reactions to goal-disruptive and goal-enhancing events (and so another fine example of an emphasis on events), these authors anticipated that goal-disruptive events would lead to immediate, within-person increases in negative affect and fatigue and that goal-enhancing events would lead to immediate, withinperson increases in positive affect. Results supported these hypotheses and suggested further that these relations are moderated by one’s immediate workload (i.e., workload increases the relations for disruptions and decreases the relation for enhancements). Notably, these authors also examined these relations at a greater period of aggregation (i.e., end of day). Generally, results were still supportive, although several relations that came out at the immediate level did not appear in the end-of-day analyses, a finding consistent with a more fine-grained experiential analysis. Of course, this is not to say that emphasizing within-person variation alone is the only endeavor of merit. In fact, recent studies have examined Reflections on Affective Events Theory 13 cross-level moderation of within-person effects with more stable, dispositional variables. Judge and Ilies (2004), for example, found evidence that dispositional levels of affect predict the strength of within-person relations between momentary affect and momentary job satisfaction. Beal, Trougakos, Weiss, and Green (2005) examined the role of stable emotion regulation strategies in predicting the strength of within-person relations between negative affect and difficulty in maintaining appropriate display rules. Results suggested that people who generally engage in surface acting strategies have a stronger relation between experiences of negative affect and difficulty maintaining display rules. AET included a role for dispositions, but not at the expense of a within-person experiential perspective. These studies provide good examples of how dispositional and within-person paradigms can be used in concert. The Phenomenal Structure of Emotions Generally, there are two main categories of affect research surrounding AET: the first is most appropriately categorized as research on diffuse affective states. Here we make a distinction between examining affect that is purely mood and examining affect that may include moods as well as other, more focused states. As discussed in Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), moods are those affective states that lack a salient target of causation. Rarely, however, have studies purporting to measure mood stuck to this definition in their measures. Frequently, the measurement of moods is broad enough to allow for the influence of discrete emotions and might be better termed core affect (Russell, 2003). Clearly there is some value to most of these measures, as researchers have found success regardless of whether affect is operationalized by focusing on a circumplex structure such as the PANAS (e.g., Judge & Ilies, 2004), using affect terms that have particular relevance for jobs (e.g., Fisher, 2000; LeBreton et al., 2004), or leaving the definition up to the participant (e.g., ‘‘I am in a good mood.’’ Fuller et al., 2003). Of course, the plethora of conceptualizations and measures of core affect have not improved our understanding as to which precise affective states are related to particular attitudes or behaviors. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996), in response to this conceptual ambiguity, called for increased attention to a second main category of affect: discrete emotions. As mentioned, many studies since then have continued in the paradigm of assessing diffuse positive and negative affective states, but some others have begun to focus their 14 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL attention on specific emotions. Two laboratory studies already mentioned fit in this category: the study by Weiss et al. (1999) examined particular events varying in their levels and forms of justice that give rise to several different discrete emotional experiences. Wiesenfeld et al. (1999) also examined justice events, but examined their influence on self-conscious emotions (e.g., guilt, shame) in particular. Lee and Allen (2002) made an unusual argument for their examination of discrete emotions. Using a larger measure of many emotions terms, these authors first partialed out variance due to the general dimensions of positive and negative affect. Presumably, they argued, existing factors beyond these two general factors represented variation in discrete emotions. They identified one such factor for discrete positive emotions and one factor for discrete negative emotions. These factors then were used to predict organizational citizenship and workplace deviance behaviors. The data suggested that variance due to negative, but not positive, discrete emotions predicted these criteria above and beyond the more general positive and negative affect dimensions. Finally, Fitness (2000) examined the causes and consequences of anger experiences at work. Her detailed dissection of anger revealed several interesting findings, including that the experience and expression of anger at work varied as a function of the status of the angered employee and the status of the provoker. Episodic Structure to Organizational Experience Arguably, all of the previously discussed tenets of AET have to this date received a reasonable amount of attention in the organizational literature. AET’s call to examine the episodic structure of our affective and social lives, however, appears to have been all but ignored. This situation is unfortunate, as research of this nature would have the potential not just to be applied to organizational contexts, but also to inform many other areas of psychology as to how we experience our world. Episodes of emotional experience have a structure that is not well represented by simple aggregations of experiences over time. They have peak moments, lingering traces, and recurrences that make questions of ‘‘How do you feel generally?’’ or even ‘‘How do you feel right now?’’ unlikely to capture the true nature of the experience. Furthermore, we see it as unlikely that emotions are the only experiences that are perceived in such a manner; rather, it is much more likely that many other experiences, at work and outside of work, share a similar phenomenological form (Beal et al., in press). Reflections on Affective Events Theory 15 THE FUTURE As we have said, Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) was intended to provide a roadmap, or ‘‘macrostructure’’ to help guide research on emotional experiences at work. The hope was that individual ‘‘microstructures’’ would eventually develop and replace the key arrows in the broad macrostructure of AET. So, for example, AET says that satisfaction is influenced by on line affective experiences, and provides a causal arrow linking these two constructs. However, this arrow is simply a place-holder for processes not described in the original paper. Similarly, AET makes a distinction between affect driven and judgment driven behaviors and provides an arrow to represent the idea that affective states have immediate and transient influences on performance related behaviors. Although Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) described various ways in which moods and discrete emotions influence behaviors and cognitions, no organizing framework was presented at that time. In fact, in some of these areas not enough was known at the time to even speculate on organizing frameworks. That was particularly true with regard to affective experiences and satisfaction judgments. Since that time more research and theory relevant to the various microstructures has appeared in the basic literature on moods and emotions. Consequently, the development of various process models to fill in the blanks might be more successful now then it would have been then. A new paper, describing the missing microstructures, AET II perhaps, would be useful but well beyond the scope of this paper. Here we will provide some general thoughts about processes embedded in some of the key ‘‘arrows’’ of the AET macrostructure. These are not meant to represent the actual microstructures of AET. Instead, they represent some general thoughts about the direction of those microstructures, using three parts of the AET macrostructure as examples. Affective Experiences Influence Job Satisfaction A number of studies have shown that aggregations of on line reports of mood states predict overall job satisfaction. These data have been taken to indicate that affective experiences at work are causal influences on satisfaction. They also beg the question about the processes to explain this casual relationship. At the time that AET was presented, very little research on relationships between momentary affective states and overall judgments had been conducted and certainly no theoretical processes had been offered. Since that time more is known, although a lot still needs to be known. 16 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL One thing that is known is that people do not simply ‘‘add up’’ their momentary states in making judgments. Kahneman (1999) makes the distinction between instant utility, momentary affective states, and more subjective aggregates such as remembered utility, satisfaction, and well-being. His research with Frederickson (summarized in Kahneman, 1999) shows that remembered utility, judgments about the overall affective experience of an episode, are predicted by peak affect and end of episode affect better than they are by average affect. Recently, Robinson and Clore (2002) provided a potential means for understanding the process of how affective experiences culminate in judgments of job satisfaction. Their theoretical examination of emotional selfreport details how the meaning of our reported emotional experiences changes depending upon the time frame over which we are asked to report it. To use job affect and job satisfaction as an example, if we asked people about their immediate affective state at some moment while at work, they would use their memory for episodic details to answer the items. So, when arriving at an answer, details of specific events and immediate appraisals are most informative. If, at the end of the week, we asked people to report on their affective experiences for that week (i.e., overall), they would likely try to recall episodic details that occurred during the week, but would undoubtedly not recall everything as clearly as at the moment at which it occurred. Robinson and Clore suggested that people may use other information from memory to fill in the gaps of their faulty memory for episodic details. This other information must come from more long-term semantic memory and represents dispositional or scenario-based information. So, as the time frame over which affect is measured increases, reports begin to resemble how someone feels generally or how someone knows they would feel in a given situation or with respect to a particular object. It seems likely that job satisfaction, measured generally, may be the combination of one’s memory for specific affective experiences and events supplemented by dispositional information or other job-relevant information stored in longterm memory. Such a formulation of job satisfaction begins to trace the arrow in the macrostructure of AET that connects affective reactions to work attitudes. Emotional States Directly Influence Performance A key contention of AET was that affective states influence performance relevant behaviors directly and that the transitory nature of these states Reflections on Affective Events Theory 17 would also render the behavioral consequences to be time limited. Reviews of the literature on behavioral consequences of moods and emotions were presented, but not in any overall framework. Recently we (Weiss, Ashkanasy, & Beal, 2004; Beal et al., in press) have presented more integrated process-oriented discussions of the affect-performance link. Beal et al. (in press) in particular, can be seen as a micro-structure for this part of the AET framework. Obviously we are not in a position here to describe that framework in detail. However, central to the framework is the development of a transitory performance construct, the performance episode, which is meant to provide a time structure for performance processes compatible with the time structure for affective states. Episodic performance, in turn, is driven by resource allocation processes. Emotional states, emotional regulation, and regulatory resources all interact to influence allocation. Finally, resource depletion and recovery processes are described to help understand the way immediate emotion processes spill over to influence performance in episodes after the emotion episode is over. It is our belief that these kinds of process models will provide the more thorough explanatory mechanisms missing in the original presentation of AET. Personality and Affective Experiences The importance of including personality constructs in the study of affective experiences is well established. The original AET model posited personality operating at a number of points in the process by which events influence reactions and reactions influence behavior. Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) had an accompanying discussion of the topic. Here we would like to briefly elaborate on the way AET suggests thinking about the role of personality, again as guidance for the development of more substantive process models. A fuller discussion can be found in Weiss and Kurek (2003). What is not always apparent when thinking about this topic is the ‘‘disconnect’’ between the types of constructs being studied. Moods and discrete emotions are states and the essential feature of states is change. If we think about the stream of experience over time we can easily picture particular moments in that stream when change occurs, when people move from one state to another. The length of time may vary, we may be in one state for a few moments, in another for a few years, but states by definition are time bound constructs. Personality is quite a different kind of construct. In contrast to states, an essential feature of personality, at least the trait variety 18 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL preferred by organizational psychologists, is stability. Traits have no on or off component. They are not time bound like states. They are timeless features of people. So immediately we see a problem when we study affect and personality. We are asking about how states, moods and emotions, characterized by their variability over time, can be explained by trait constructs characterized by stability. How can something that does not change explain something for which change is the essential feature? Organizational researchers have solved this problem in a number of ways and the most prevalent ways are by far the least interesting. One way, of course, is to substitute relatively stable ‘‘affect like’’ constructs for true affective experiences. Satisfaction, strain, burnout, etc. are conceptually and methodologically easier to relate to personality because they too are not defined by change. Another way is to aggregate the affective experiences over time, usually by asking people to report on affective tendencies or summated experiences. Regardless of whether people can do that with any degree of accuracy (and all indications are that they cannot) the exercise itself treats within-person variability as error. That within-person variability is substantial and certainly not error. For many it is the most interesting piece of the puzzle. Mischel and Shoda (1995, 1998) have described two traditions in personality research. The first tradition, the behavioral disposition tradition, focuses on relating personality to consistencies in behaviors by ignoring the within-person variability in those behaviors. This is clearly the approach taken in the I/O literature with regard to personality and affect. The other approach, the mediational process approach, seeks to take the within-person variability seriously and carve out a role for personality in process explanations for behavioral change. We believe the latter approach is the approach of choice for affect. Instead of predicting the stability in moods and emotions we should be looking at the multiple ways in which personality enters in to the causal chain of emotion generation, emotion regulation, behavioral choice, etc. This approach has yet to be seen with any frequency. SOME FINAL THOUGHTS In inviting us to contribute a chapter to this volume we were asked to comment on the role of AET in the recent history of research on workplace emotions. Driven by an explosion of basic research on emotions, Reflections on Affective Events Theory 19 organizational psychologists were already making progress in the study of emotions at work before the introduction of AET and it goes without saying that important research of high quality was and is being conducted uninfluenced by Weiss and Cropanzano (1996). Yet, since its publication, Weiss and Cropanzano and the AET framework has been cited in much if not most of the papers on workplace emotion and AET is frequently mentioned as an important organizing framework for the field. Consequently, some sort of commentary is perhaps warranted. Here we have argued that the influence of a paper is not judged by the number of citations or the frequency of testimonials. Rather, influence is to be judged by the extent to which the positions taken in the paper, its research suggestions, its basic premises, etc. inform subsequent work. Even here influence can be hard to discern. Many of the suggestions of AET are direct outgrowths of the existing basic literature on emotions. Organizational scholars who took that literature seriously would come to the same conclusions as Weiss and Cropanzano (1996) did anyway. Nonetheless, Weiss and Cropanzano did articulate an organizing framework and a series of premises and assumptions different from prevailing approaches. Our review of the literature tells us that the glass is both half full and half empty. It is half full in the sense that the nature of emotion research has changed in ways suggested by Weiss and Cropanzano (1996). A number of assumptions have been tested and premises accepted. It is half empty in that the detailed formulation of process needed to fill in the blanks of the AET macrostructure have not been forthcoming. Despite this pessimistic interpretation, however, it is perhaps too early to expect such elaborate process models to have taken hold in the organizational literature. We see this as the next step for the study of emotions in the workplace, and, therefore, conclude that the wave of emotion research has not yet reached its peak. REFERENCES Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1995). Emotion in the workplace: A reappraisal. Human Relations, 48, 97–125. Averill, J. R. (1980). On the paucity of positive emotions. In: K. Blankstein, P. Pliner & J. Polivy (Eds), Advances in the study of communication and affect, (Vol. 6, p. 745). New York: Plenum. Ayoko, O. B., Callan, V. J., & Härtel, C. E. J. (2003). Workplace conflict, bullying and counterproductive behaviors. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 11, 283–301. Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323–370. 20 HOWARD M. WEISS AND DANIEL J. BEAL Beal, D. J., Trougakos, J. P., Weiss, H. M., & Green, S. G. (2005). Episodic processes in emotional labor: Perceptions of affective delivery and regulation strategies. Manuscript under review. Beal, D. J., & Weiss, H. M. (2003). Methods of ecological momentary assessment in organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 6, 440–464. Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (in press). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. Burke, M. J., Brief, A. P., George, J. M., Roberson, L., & Webster, J. (1989). Measuring affect at work: Confirmatory analyses of competing mood structures with conceptual linkages to cortical regulatory systems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1091– 2102. Conway, N., & Briner, R. B. (2002). A daily diary study of affective responses to psychological contract breach and exceeded promises. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 287–302. Fineman, S. (1993). Emotion in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA, U.S.: Sage Publications, Inc. Fisher, C. D. (2000). Mood and emotions while working: Missing pieces of job satisfaction? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 185–202. Fisher, C. D. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of real-time affective reactions at work. Motivation & Emotion, 26, 3–30. Fisher, C. D. (2003). Why do lay people believe that satisfaction and performance are correlated? Possible sources of a commonsense theory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 753–777. Fitness, J. (2000). Anger in the workplace: An emotion script approach to anger episodes between workers and their superiors, co-workers and subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 147–162. Frijda, N. H. (1993). Moods, emotion episodes, and emotions. In: M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds), Handbook of emotions (pp. 381–404). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Fuller, J. A., Stanton, J. M., Fisher, G. G., Spitzmüller, C., Russell, S. S., & Smith, P. C. (2003). A lengthy look at the daily grind: Time series analysis of events, mood, stress, and satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1019–1033. George, J. M. (1989). Mood and absence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 317–324. George, J. M. (1990). Personality, affect and behavior in groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 107–116. George, J. M. (1991). State or trait: Effects of positive mood on prosocial behaviors at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 299–307. Grandey, A. A., Tam, A. P., & Brauburger, A. L. (2002). Affective states and traits in the workplace: Diary and survey data from young workers. Motivation and Emotion, 26, 31–55. Ilies, R., & Judge, T. A. (2002). Understanding the dynamic relationship between personality, mood, and job satisfaction: A field experience sampling study. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 1119–1139. Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2004). Affect and job satisfaction: A study of their relationship at work and at home. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 661–673. Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In: D. Kahneman & E. Diener (Eds), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. LeBreton, J. M., Binning, J. F., Adorno, A. J., & Melcher, K. M. (2004). Importance of personality and job-specific affect for predicting job attitudes and withdrawal behavior. Organizational Research Methods, 7, 300–325. Reflections on Affective Events Theory 21 Lee, K., & Allen, N. J. (2002). Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: The role of affect and cognitions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 131–142. Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: Reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246–268. Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1998). Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annual Review of Psychology, 49, 229–258. O’Shea, M., Ashkanasy, N. M., & Gallois, C. (2002). Emotion as a mediator of work attitudes and behavioral intentions. Paper presented at the 17th annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Paterson, J. M., & Cary, J. (2002). Organizational justice, change anxiety, and acceptance of downsizing: Preliminary tests of an AET-based model. Motivation & Emotion, 26, 83–103. Pekrun, R., & Frese, M. (1992). Emotions in work and achievement. International Review of I/O Psychology, 7, 153–200. Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief and feeling: Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 934–960. Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110, 145–172. Schaubroeck, J., & Lam, S. S. K. (2004). Comparing lots before and after: Promotion rejectees’ invidious reactions to promotees. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 94, 33–47. Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2003). Emotion regulation in customer service roles: Testing a model of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 55–73. Weiss, H. M. (2002). Deconstructing job satisfaction: Separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences. Human Resource Management Review, 12, 173–194. Weiss, H. M., Ashkanasy, N. M., & Beal, D. J. (2004). Attentional and regulatory mechanisms of momentary work motivation and performance. In: J. P. Forgas, K. D. Williams & W. Von Hippel (Eds), Social motivation: Conscious and unconscious processes (pp. 314– 331). New York, NY: Psychology Press. Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In: B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds), Research in organizational behavior, (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Weiss, H. M., & Kurek, K. E. (2003). Dispositional influences on affective experiences at work. In: M. R. Barrick & A. M. Ryan (Eds), Personality and work (pp. 121–149). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Weiss, H. M., Nicholas, J. P., & Daus, C. (1999). An examination of the joint effects of affective experiences and job beliefs on job satisfaction and variations in affective experiences over time. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 78, 1–24. Weiss, H. M., Suckow, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). Effects of justice conditions on discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 786–794. Wiesenfeld, B. M., Brockner, J., & Martin, C. (1999). A self-affirmation analysis of survivors’ reactions to unfair organizational downsizings. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 441–460. Zohar, D., Tzischinski, O., & Epstein, R. (2003). Effects of energy availability on immediate and delayed emotional reactions to work events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1082–1093.