The Case for International Accounting Standards in Canada

advertisement

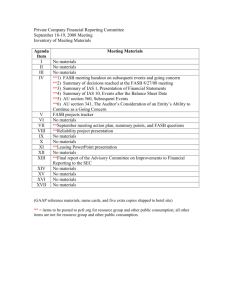

C E R T I FI E D GE NE R AL AC C OU NTANTS AS S OC I AT IO N OF CANADA The Case for International Accounting Standards in Canada Table of Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................3 Introduction ......................................................................................................................5 Adopting FASB Standards Would be a Flawed Choice ..................................................5 Accepting FASB Standards Would be Shortsighted ........................................................7 FASB Standards Could Lead to Unnecessary Costs and Delays......................................7 Long-Term Considerations Should Take Precedence ....................................................8 No Country is an Island Anymore ....................................................................................8 Growing Influence of International Standards .............................................................. 9 Canadian GAAP Closer to IASC Standards ....................................................................9 IASC Standards More Open to Political Representation ............................................10 IASC More in Tune with Its Users ................................................................................10 IASC Standards Better for SMEs ....................................................................................10 Canada’s Contribution to the Influence of IASC Standards ........................................11 A New Role for Canadian Standard Setters Internationally..........................................11 Setting Local Standards When Needed ..........................................................................11 Canadian Standard-Setting Process Out of Step ............................................................12 Conclusions ......................................................................................................................12 1 Executive Summary With the dawning of the millennium close at hand, Canada has reached an important crossroads in accounting standard setting. We are now faced with making a strategic decision to ensure Canada’s continued leadership role in this field well into the 21st century. The heart of the decision revolves around one important question: should Canada preserve the status quo by continuing to establish its own national accounting standards, or should it adopt standards more conducive to globalization and international business co-operation? CGA-Canada believes the status quo should be abandoned in favour of international accounting standards. Why is this decision so important? Harmonized global standards would ensure that financial statements carry enormous credibility. Users could pick up statements originating from different countries secure in the knowledge that such documents were prepared using a consistent approach. Besides the obvious implications to management and shareholders of Canadian organizations, the choice of accounting standards drives many larger public policy issues with implications for everything from government interests to trade and commerce, taxation and economic planning. Abandoning the status quo to adopt new standards for the next century will, however, require an additional decision. Which set of standards should be used globally? The choice on the international stage has boiled down to the standards set by the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC), or those set by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the body responsible for establishing generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the United States. CGA-Canada believes that adopting IASC standards in Canada would be the correct choice for several reasons, among them: ◆ In recent years, the IASC’s influence has been clearly and unmistakably gaining momentum around the world. Its international standards have been accepted by industrial and developing nations alike, and this trend is expected to continue. ◆ The adoption of IASC standards as the single dominant measure of financial results is no longer a question of “if,” but “when.” Therefore, Canadian authorities would be prudent to ensure we are part of a network with the greatest number of users. ◆ In this age of rapid technological growth and globalization, Canada must be prepared to define its position on the international standards debate now or risk being thrust into a marginal role. Although Canada has a vital role to play on the international stage, it must also continue to utilize a national standard-setting body capable of maintaining a domestic focus when special occasions or local conditions dictate. 3 The issue of accounting standards is, however, too important a matter for one private body to administer, as is the case today. Users of financial statements come from the community at large. Small business owners, financial planners and others are all affected by decisions about the nature and quality of the information reported. The ensuing debate on the most appropriate accounting standards for Canada must, therefore, take place in the public realm, with parliamentary participation. 4 The Case for International Accounting Standards in Canada INTRODUCTION Standards are important to any society. They provide a means to measure, compare, co-ordinate and protect. They can be applied to myriad functions, ranging from weights and measures, to traffic control and monetary systems. Accounting standards also fulfil an important function. For instance, they protect third-party interests by providing financial statement users a common yardstick with which to compare alternatives and come to reasonable decisions. These standards also allow financial statement users, who compare the relative performance of different companies, to feel confident that the methods used to prepare such financial statements are consistent. They protect investors, shareholders and the government from biased or inconsistent reporting by management. In contrast, financial statements prepared using different sets of ground rules run the risk of reporting dramatically different financial results. Harmonized global standards, therefore, would ensure that financial statements are prepared consistently and carry credibility. So, as the world becomes increasingly globalized, Canada has to come to a decision about accounting standards. Should Canada preserve the status quo by continuing to establish its own national accounting standards, or should it adopt standards more conducive to globalization and international business co-operation? CGA-Canada believes the future lies in internationally adopted accounting standards. But which set of standards? From a public policy perspective, selecting the right set of accounting standards is crucial because a number of issues, with implications for trade and commerce, taxation and economic planning, hinge on the decision. As it stands, the choice on the international stage has boiled down to the standards set by the International Accounting Standards Committee (IASC) or the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), the body responsible for establishing generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in the United States. ADOPTING FASB STANDARDS WOULD BE A FLAWED CHOICE Many interested parties are today proposing that Canadian standards be harmonized with FASB accounting standards, especially because of Canada’s close ties with the United States. The United States is Canada’s predominant trade and investment partner. In 1997, for instance, Statistics Canada reported that the United States accounted for 68% of all Canadian imports and 82% of exports. In the short term, these statistics might seem to favour the adoption of FASB accounting standards. Supporters of this view point out that substantial progress has been made in recent years toward reducing some of the differences between U.S. and Canadian GAAP and that the two countries have worked closely 5 together to develop joint standards in several key areas. There are, in fact, some Canadian companies who benefit from and have chosen to apply FASB standards. However, these represent only a very small minority who presumably will continue to apply a U.S.-style approach, regardless of how Canada chooses to proceed on this issue. Despite these economic ties between Canada and the United States, there are many compelling reasons why it would not be prudent for Canada to adopt FASB standards. FASB standards are, for instance, the result of a “closed process” designed to accommodate U.S. interests. Also, they have been established primarily for the benefit of investors to the exclusion of other groups in society interested in corporate performance. Moreover, FASB standards are designed to function within a very litigious environment. From an auditor’s perspective, it’s best to have a set of standards that provide definitive guidance as to what is acceptable and what is not as protection against undue risk and potential lawsuits. There are other differences, too. Historically, Canadian accounting standards have provided more room for the application of professional judgment than those issued in the United States, which are more rule-oriented and prescriptive. The government and legal systems in commonwealth countries are designed to give auditors more leeway in using professional judgment, provided the overall intent is to make things clearer to the investing public. This amounts to a “true and fair” notion that can override standard principles. If FASB standards are adopted in Canada, however, much of the flexibility allowed under current Canadian and international rules would be lost. The growing international acceptance of IASC standards also shows that FASB standards are not the right choice. Today, only 10 countries accept financial statements based on FASB standards and nine of those (with the exception of Israel), also allow published statements predicated on IASC standards. In contrast, no less than 46 countries have formally committed to harmonize their national standards with IASs; this number does not include countries with standards based on IASs, but which have not issued an explicit policy statement to this effect, or countries that accept statements based on IASs along with those based on domestic standards. In fact, Canada and the United States are currently the only major industrialized nations that do not accept financial statements prepared using IASs. This increasing support for IASC standards, coupled with the growth of foreign stock exchanges, makes it unlikely that FASB will pick up further support in the future. Many corporate executives question why they should have to go through the expense of listing in the United States, then changing to accommodate international standards. Stock exchanges around the world are growing in size and stature and doing a credible job raising capital, which has contributed to shifting international patterns. The growth of computerized stock trading also implies that investors will find the most efficient capital markets, regardless of national regulatory structures. Despite the FASB’s influence today, many experts believe IASC standards are destined to become the global “standard” over the next 10 to 15 years. Joint efforts by both the IASC and FASB, backed by other members of the G4+1 — which consists of the standardsetting bodies of the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia/New Zealand and the IASC — have led to substantial harmonization in several key areas over the past 6 five years. The results have served to reinforce many expert opinions that IASC standards will eventually emerge as the true backbone for international accounting. Finally, ceding control of our accounting standards to the United States would not be a popular political move. Is the federal government prepared to perpetuate what many feel is already a case of U.S. domination? Will it let American accounting rules define a key starting point for the direction of Canadian tax measures and related public policy implications? ACCEPTING FASB STANDARDS WOULD BE SHORTSIGHTED If Canada chooses to limit its perspective to a North American context and go with FASB standards, it would be ignoring a golden opportunity to seize a bold position on the international stage. By electing to adopt FASB standards, we would be reinforcing the notion of isolated trade, rather than integration between the major European Union and North American trading blocs. This would make it more difficult for Canadian companies to compete in the international arena during an era when both the public and private sectors are working feverishly to promote Canadian expertise overseas. We would also be doing the international accounting community a disservice by remaining confined to the North American “backyard” until the United States decides to move on this issue. Considering its European heritage and close economic ties to the United States, Canada has a role to play in building a bridge between the two continents. Therefore, adopting FASB standards would be shortsighted. More specifically, it would: ◆ represent a serious blow to the prospects for achieving the international harmonization of accounting standards; ◆ seriously undermine the credibility and influence of the Canadian accounting profession at the international level; ◆ limit the acceptance of Canadian financial statements outside of North America; and ◆ promote the view that Canada, which would never be in a strong position to exercise control over the FASB process, lacks independence from U.S. standard setters. FASB STANDARDS COULD LEAD TO UNNECESSARY COSTS AND DELAYS The total cost of converting to a new set of standards must take into account Canadian participation in the standard-setting process, as well as the costs of compliance faced by financial statement preparers. Harmonized standards that streamline financial reporting activities, such as those developed jointly by the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) and IASC, tend to avoid cost duplication. Therefore, individual companies, especially small Canadian businesses, may find it less costly to convert to IASC standards, particularly since a concerted effort to further harmonize Canadian and international standards has taken place in recent years. Conversely, rigid standards that allow for little managerial discretion, such as those of FASB, usually entail high compliance costs. Harmonization with the FASB model would not only likely contribute toward a longer global transition period, but lead to unnecessary costs and delays as well. 7 LONG-TERM CONSIDERATIONS SHOULD TAKE PRECEDENCE Although Canada today is more economically dependent on the United States for trade and capital than on any other country, the short-term benefits of adopting FASB standards would be mitigated by several factors, including the much wider acceptance of IASC standards by dozens of countries worldwide. IASC standards are especially popular in Europe; several countries have adopted international standards in place of, or alongside, their own. This reflects the trend of European countries breaking down political and economic barriers in the past 25 years. The international orientation of business is another compelling argument for harmonized international accounting and auditing standards. As globalization heralds a changing pattern of investment and capital formation, Canada should join and contribute toward the same standard-setting regime that applies to the majority of its trading partners and capital suppliers. Furthermore, if accepting FASB standards is merely an intermediate step on the road to the eventual acceptance of IASC standards, as many believe it would be, Canada should proceed directly to adopting international standards rather than chart a more time-consuming and expensive interim course. NO COUNTRY IS AN ISLAND ANYMORE National standards worked well in Canada when it was a reasonably self-contained economic unit and the accounting profession was small and culturally homogeneous. But the increased flow of international trade in today’s global economy represents a break with the past. The issue at present is how Canada can best integrate itself into a global realm, while maintaining the representational gains made on a domestic level. The case for a wholesale set of “distinctively Canadian” standards has been significantly weakened in recent years. Unique Canadian standards in a country whose stock exchanges only account for about three per cent of total (listed) global market capital can be expected to become increasingly rare as international standards are accepted on a global basis. It doesn’t make sense to continue spending inordinate amounts of time and money to maintain our own standards if they aren’t going to provide much in the way of original content. Therefore, the potentially significant costs of complying with different reporting requirements to maintain the status quo can no longer be justified. Nor does the speed of international business permit the luxury of standard setting at a “Canadian” pace in this day and age. In the future, the number of standards-related issues unique to Canada is expected to decrease even further. Potential participants are increasingly likely to opt out of “made in Canada” solutions because they won’t see the justification or philosophical need for maintaining a different set of accounting standards in a global economy. With a growing demand for a common financial reporting “language” to accommodate globalization of financial markets, different sets of national reporting standards will be perceived as creating competitive disadvantages that work against the free flow of capital across international borders. 8 GROWING INFLUENCE OF INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS Until recently, Canada and the United States were considered world leaders in the establishment of sophisticated standard-setting capabilities and processes. The IASC, on the other hand, operated as a technical body primarily concerned with eliminating bad practices, particularly during its formative years. But the international landscape has changed dramatically in recent times — other countries have developed accounting processes and standards comparable in quality to those in North America. The IASC has become very influential, both in playing a leading role and in emerging as a credible body for creating new international standards. It has also reached sensible working arrangements with securities regulators around the world. In 1996, the World Trade Organization, a body Canada was instrumental in helping to establish, provided a significant boost to the international effort to harmonize accounting standards by issuing a statement of support for the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC) and the IASC. CANADIAN GAAP CLOSER TO IASC STANDARDS Canada has always worked in conjunction with the IASC to minimize differences between international standards and Canadian GAAP. In recent years, for instance, Canadian and IASC officials have worked jointly on the financial instruments project, ensuring the broad comparability of section 3860 of the CICA Handbook and IASC Standard 32. Also, section 1501 in the CICA Handbook recognizes the importance of international harmonization by allowing Canadian firms to take advantage of benefits derived from situations where Canadian and international standards are in agreement. Adapting to U.S. standards, on the other hand, may entail a whole new paradigm. For instance, Canadian GAAP allows certain development expenditures associated with research and development projects to be capitalized and apportioned over the life of a project, whereas under U.S. GAAP those costs are immediately expensed. With respect to business combinations, Canadian and international standards both require that the purchase method of accounting be used. There is some allowance for the pooling of interests method, but only under exceptional circumstances such as when an acquirer cannot be identified and the transaction represents a “true” pooling of business interests. Historically, a large percentage of business mergers in the United States have been accounted for using the pooling of interests method, although FASB recently announced it intends to ban this process. International standards also exhibit a greater degree of compatibility with Canadian standards because of the level of disclosure involved. For example, IASC rules require financial statements to be “true and fair,” while FASB standards are more technical in nature, with a heavier emphasis on conformance to GAAP. IASC and Canadian standards also allow more leeway for professional judgment. Under IASC rules, an auditor can use discretion to determine that certain rules and procedures (i.e., those that unnecessarily disclose competitive information) might not apply under special circumstances. 9 Given the greater flexibility and compatibility of IASC benchmarks, Canada could probably adopt most without major changes. By comparison, the adoption of FASB standards might entail major modifications before they would work in Canada. Clearly, since IASC standards are already more similar in style and content to Canadian GAAP, it makes more sense for Canada to harmonize with international, rather than FASB standards. IASC STANDARDS MORE OPEN TO POLITICAL REPRESENTATION Standards generated at the international level must be flexible enough to allow a sovereign nation to continue doing what it needs to do. IASC accounting standards are more compatible with Canadian interests in that sense because they are more open to political representation and social choice. IASC standards allow for direct representation of national interests and are funded by professional accounting associations representing several countries. They are rooted in a consultative parliamentary approach, which lends itself to decisions achieved by consensus and co-operation in a global environment. Having a number of national standard setters proactively involved in the international standard-setting arena also encourages healthy debate. Something that may be perfectly acceptable in Britain, for example, may not be acceptable in Canada, Germany or Japan. The process invites compromises and sensitivity on political issues. In contrast, the current FASB structure is designed with little room for non-U.S. involvement at the board level. It is funded by the independent Financial Accounting Foundation, whose members are drawn from U.S. industry, academe and the profession. Members are expected to act in a nonpartisan manner, formally severing ties with previous employers upon joining the standard-setting body. IASC MORE IN TUNE WITH ITS USERS Over time, standard setters have been faced with an increasing diversity of constituents and changing social values. According to Canadian GAAP, the financial statements of profit-oriented enterprises must focus on the information needs of investors and creditors, while the statements of not-for-profit enterprises should address the information requirements of members, creditors and contributors. To that end, the standard-setting process must now seek legitimization from the wider community on grounds that may not always be entirely consistent with technical criteria. The flexibility of IASC standards, as compared to the more rigid standards established by FASB, better reflect the wider audience of financial statements users. IASC STANDARDS BETTER FOR SMES A complaint often levied against both Canadian and U.S. rules is that they tend to be designed more for the benefit of large businesses, whereas a more consensus-oriented body would better represent the interests of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). 10 For SMEs, such as a retail store with $500,000 in assets, existing rules sometimes lead to a serious issue in terms of regulatory overload. The relative flexibility of IASC standards would better service SMEs by being more sensitive to their needs and interests. CANADA’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE INFLUENCE OF IASC STANDARDS The IASC was established by the accounting profession in Canada and eight other countries in 1973 in recognition of the need for the international harmonization of accounting standards. Canada, with its established standard-setting experience, has contributed greatly to the increased quality of international standards. As far back as 1988, for instance, CICA and IASC representatives teamed up on a joint project examining financial instrument recognition, measurement and disclosure standards. Canada has earned a great deal of respect at the IASC level over the past 25 years as a middle power broker or facilitator. And we are much more likely to be able to influence the international process by continuing in that capacity than we are to influence FASB standards in any meaningful way. Adopting international standards would also allow us to continue in a high profile role and remain actively involved in setting the IASC agenda. The international standardsetting process has much to gain in the future from Canadian knowledge and expertise. A NEW ROLE FOR CANADIAN STANDARD SETTERS INTERNATIONALLY Canada has a long and reputable history of accounting standard setting and, though it is important for us to maintain our autonomy, the time has come for us to accept a new role. As international standards gain widespread acceptance, it no longer makes sense for Canadian standard setters to independently research and debate accounting issues as they have in the past. Today, we must be prepared to work with other nations in developing a single set of internationally accepted accounting standards. Establishing a common accounting language will also help facilitate the free flow of capital within and across national boundaries in the global economy. SETTING LOCAL STANDARDS WHEN NEEDED Unique situations and circumstances are always bound to arise in any country, whether for political, economic or other reasons. Professional accounting is no exception. There will be situations where a Canadian standard, dealing with the effects of Canadian law or purely Canadian economic, legislative or regulatory issues, must be accommodated. Because national bodies have an important role to play in disseminating national standards and providing support for international standards, an open standard-setting process should be maintained at both levels. A move to international standards does not undermine the legitimacy or importance of Canadian standards. Commitments to the use of international accounting standards can be modified as necessary to meet local needs. Investment tax credits, for example, are currently treated 11 differently in Canada than in the United States. Any international standard on investment tax credits would have to reflect local laws, regulations and recommendations. The national regulatory apparatus will continue to play a valuable role, both in developing and enforcing financial reporting and auditing standards, as well as in regulating the competency of individuals who practise public accounting. A full-time board with the authority to set standards and deal with emerging issues would also be poised to deal with special Canadian problems. Where the Canadian-established practice appears to be the best solution, it should then be promoted as a model for other international standard setters. CANADIAN STANDARD-SETTING PROCESS OUT OF STEP Canada is the only nation in the industrialized world where a single, private accounting organization, which excludes about half the profession, has been delegated quasilegislative authority to set standards. Other countries traditionally maintain this process at arm’s length from the accounting profession. Membership in standard-setting bodies in many countries includes representatives of interest groups from a number of sectors including, but not limited to, the accounting profession. The same should be true in Canada. In today’s complex society, the development of accounting standards should no longer be the sole domain of a single group of professionals, let alone a solitary body. CGA-Canada recommends that Canada join the ranks of nations like the United Kingdom and Australia in establishing an independent, publicly accountable and broadly based accounting standard-setting body. The U.K. Accounting Standards Board, for instance, is mandated by legislation and comprises representatives from various accounting bodies, academia and others, for an open standard-setting process. A new standardsetting body in Canada could, for instance, be composed of key stakeholders, including representatives from the banking and legal community, government and businesses that would be impacted by the process. A move to international standards could therefore provide Canada with unique opportunities to bring our standard-setting process in line with that practised in other countries. For instance, multiple body representation would not only provide Canada with better representation at the IASC level, but also an opportunity to establish accounting standards with a greater degree of independence. Moreover, having a diverse group participating in the standard-setting process would eliminate the possibility of real or perceived conflicts of interest. It would also facilitate a broader response to emerging issues, interpretations or other guidance required. CONCLUSIONS To put it simply, choosing the right set of accounting standards is analogous to selecting a telephone system. Naturally, one would prefer to be connected to the one with the greatest number of users in order to maximize the number of direct connections. 12 So, when selecting the appropriate accounting standard-setting regime, Canadian authorities would be prudent to choose the international standards published by the IASC, in order to ensure we are part of the network with the greatest number of users. Although distinct cultures and political systems still exist in the world, overall differences are on the decline as nations become more socially and economically integrated with one another. Global ties only serve to reinforce the argument that international accounting standards will eventually dominate. Global harmonization of accounting standards would also provide financial statements with an enormous amount of credibility in the eyes of financial statement users. Users could pick up financial statements originating in different countries, secure in the knowledge that such statements were prepared using an approach endorsed by comparable principles. Flexible accounting standards, such as those put forth by the IASC, would also make it easier for capital markets and other users to obtain comparable financial information. Under a more rigid set of accounting rules, such as those of FASB, it would be more difficult and expensive to gather and present such information. Failure to adjust Canada’s standard-setting model to deal with the new global realities could seriously hamper our ability to compete internationally. Although Canada has an important role to play in establishing international standards, we must continue to support a national standard-setting body to maintain a domestic focus when appropriate. The issue of accounting standards is, however, too important a matter for Canada to leave to a single private body. Accounting standards are a matter of public policy that should reflect community standards. An increasingly broad range of financial information users are demanding that their views be represented in the standard-setting process. In conclusion, a broad public discussion on the issue of Canadian and international accounting standards is warranted, involving both the federal government and various constituents within society at large. 13