Baker, T - 2012 Fall WS

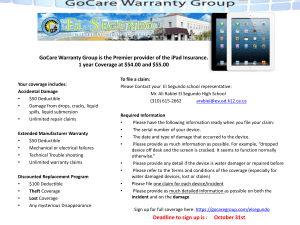

advertisement