yale case 07-034 september 7, 2007

Thomas Weisel Partners

An IPO Breathed New Life Into A West Coast Investment Bank,

But Where Should The Firm Go From There?

Allison Mitkowski1

Mark Manson2

Jaan Elias 3

The West Coast investment bank Thomas Weisel Partners (TWP), founded by the legendary

Silicon Valley entrepreneur Thomas Weisel, enjoyed one of the most successful start-ups of a

financial services firm in history. Valued at $500 million when it opened for business in January

1999, TWP - which focused its efforts primarily on the technology industry – raked in $662

million in net revenues during its first two years and executed deals for high-profile clients like

Yahoo! and MapQuest.com.

But in 2001, the private boutique firm was hit hard by the implosion of the dot-com, telecom and

technology industries, which comprised the bulk of the TWP’s investment banking business. The

downturn in the economy led Weisel to restructure his business; he diversified into healthcare

and consumer, built out his PIPES and M&A practices, and reorganized his research department

to lessen the focus on the telecom sector. But the firm continued to struggle financially, and its

partners were seeing minimal profits from the time and money they had invested in TWP.

The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 and the corporate scandals that dominated the early part of

the decade further devastated the securities market, and TWP’s partners were left to wonder if, or

when, the firm could ever make a comeback. At the end of 2004, some key partners began

pondering the future of TWP, and considering the most drastic change of all – turning the

private partnership into a publicly owned company. Certainly, an IPO would give the firm an

infusion of capital, but going public meant making crucial decisions about the timing of the

offering and the underwriter, among other things. It also raised questions about how the new

ownership structure would affect TWP’s processes and its entrepreneurial culture. Finally and

most importantly, the management had to consider how they would invest the proceeds from an

IPO to best position the bank for the future.

Driven to Succeed

The Road to Thom Weisel’s Success in Silicon Valley

Observers attributed TWP’s quick ascent to the firm’s strong leadership, Weisel’s vast network of

carefully cultivated contacts, and particularly, the employees’ in-depth knowledge of the

industries in which they did business. Weisel explained:

Our bankers have a much deeper domain expertise. If you compare us with the big firms, their

bankers are very, very good at doing transactions. We have bankers who know enough about

the software business to identify with the CEO of a software company, whereas most bankers at

the big firms don’t have the same capability. In addition, our firm is geared to service emerging

growth companies whereas the large firms are not.

Those close to Weisel say he has an intense work ethic and an obsessive drive to succeed. His father,

Wilson Weisel, was a surgeon who set high standards for his three children. As a teenager growing up in

Milwaukee, Weisel carved out a niche as a fierce athletic competitor. He won five national speed-skating

titles before going on to train for the Olympics during his freshman year at Stanford.4 His passion for

competitive athletics broadened throughout his adult life, and he became a top-notch competitive runner,

skier and cyclist. He served as chairman of the U.S. Ski Team during the 1980s and early 1990s, and he

also founded the U.S. Postal Service/Discovery Cycling Team, for which Lance Armstrong has won seven

Tour de France championship titles.

After graduating from Harvard Business School in 1963, Weisel’s life’s goal was not to make a fortune on

Wall Street, as most of his classmates wished. Rather, he coveted a San Francisco address. So Weisel

headed for California, much to the dismay of one of his favorite professors at HBS, C. Rowland

Christianson, who railed, “What the hell are you doing? Don’t you want to be where the opportunities

are?”5

At the time, San Francisco was not considered a major financial center. But in the area around Stanford

University, there was a nascent network of entrepreneurial companies that would later become Silicon

Valley. Small, high-tech firms were springing up and creating technologies that would fuel a revolution in

computing and communications. Investors with impressive technical knowledge were aiding in the

formation of these small ventures, creating a system of venture capital and angel investors to push the

growth of these new firms.

Weisel spent his first few months in San Francisco without a job. He eventually took a position as an

investment analyst for a food machinery company to pay the bills, but ultimately he decided to pursue a

career as an entrepreneur in finance. A friend of Weisel’s from Stanford referred him to a colleague who

helped him get a job at a new investment bank, William Hutchinson & Co.6 Weisel worked there for four

years before leaving to become a partner at another investment bank, Robertson, Coleman, Siebel &

Weisel, which specialized in Silicon Valley technology companies. While there, Weisel focused on

building a competitive institutional business – a move that enabled him to retain the partnership after

three of the founding name partners resigned. Weisel took control of the firm, renamed it Montgomery

Securities (after Montgomery Street, the heart of San Francisco’s financial district), and kept the firm’s

seat on the New York Stock Exchange.7

Under Weisel’s leadership, Montgomery Securities quickly earned a reputation as an aggressive, noholds-barred operation, referred to as a “jock shop” by some, in part because of Weisel’s penchant for

competitive athletics. As a banker who also wanted to be an entrepreneur, Weisel seemed to be a perfect

fit with the bright young engineers leading technology firms and the venture capitalists in the Bay Area.8

The firm specialized in underwriting and trading the securities of small growth companies. With its

specialized knowledge, Montgomery could compete with top Wall Street banks, and by 1996, the firm

had earned a No. 10 ranking in equity underwriting and initial public offerings.9

However, during the 1990s, the financial services industry was undergoing a radical transformation. The

1933 Glass-Steagall Act had prohibited investment banks that underwrote securities from engaging in

commercial banking activities. But throughout the 1990s, financial services firms were merging

operations and gaining regulatory approval for combinations of commercial and investment services

(Glass-Steagall was officially repealed in 1999, but regulators had stopped enforcing many provisions of

the act well before that time). These regulatory changes led to consolidation in the financial services

2 thomas weisel partners

industry, which enabled new megabanks to provide companies with a greater range of services, including

access to large pools of capital and “one-stop shopping” for financing needs.

The rise of these new megabanks posed a threat to Montgomery’s livelihood, and Weisel knew that his

firm would need the support of a strong partner to survive the consolidation of the banking industry.

Large commercial banks had already acquired two investment banks similar in size and scope to

Montgomery, Alex. Brown and Robertson Stephens. In addition, Wall Street banks had already begun to

nab long-time Montgomery clients because Montgomery didn’t have the capital or the debt capacity to

compete. “We were clearly getting beaten out,” observed Weisel. “If we said, ‘We’ll put a syndicate

10

together,’ and someone else said, ‘We’ll take the whole thing,’ who do you think got the business?”

So on June 30, 1997, Weisel and the partners at Montgomery Securities sold the business to North

Carolina-based NationsBank, now known as Bank of America, for $1.3 billion. Montgomery’s 68 partners

received $840 million in cash up front and $360 million in NationsBank stock to be distributed over three

years. Montgomery became a subsidiary of NationsBank with Weisel serving as division chairman and

CEO of NationsBanc Montgomery Securities Inc.11

Weisel had been leery of the culture clash that might occur between his entrepreneurial band of partners

and the more hierarchical and fiscally conservative bankers at NationsBank. Therefore, prior to the

merger, he negotiated a detailed agreement with NationsBank that spelled out the interactions between

NationsBank and his division. The agreement called for keeping the two organizations, by-and-large,

separate and autonomous.

In the first six months after the merger, NationsBanc Montgomery’s business increased by more than 50

percent. The company worked on IPOs for Internet-focused companies, such as InfoSpace.com, and

completed underwritings for tech outfits like Applied Micro Circuits. But Weisel’s success at NationsBanc

Montgomery was short-lived. In spite of the merger agreements, NationsBank executives began to

micromanage Weisel and his team. The ensuing turf wars led many at NationsBank to call for merging

Weisel’s organization into the overall bank.12

Citing an infringement upon the merger agreements he signed with NationsBank, Weisel resigned in

September 1998.13 Although the highly publicized fracas with NationsBank ended Weisel’s long and

storied career at Montgomery, those in Silicon Valley who had worked closely with Weisel over the years

knew that he wasn’t about to vanish from the investment banking scene. “Thom Weisel is an incredibly

talented, if controversial and independent, personality,” Dan Case, chairman and CEO of the major

Silicon Valley investment bank Hambrecht & Quist, said after Weisel’s departure. “Nobody should

underestimate him. He is not a guy one would expect to retire at the beach.”14

Weisel’s Vision for a New Kind of Bank

Indeed, retirement was far from Weisel’s mind. He had spent his final months at NationsBanc

Montgomery brainstorming ways to fix what he described as a broken investment banking model. He

despised the transaction-oriented culture that prevailed within the industry, believing instead in

nurturing long-term relationships with small, growth companies, which often meant initiating and

maintaining contact with clients for years before they called upon his firm’s services.

Weisel also felt that investment banks had become too bureaucratic and inflexible, and he saw talented

bankers who inked the same types of deals over and over again becoming frustrated by the monotony of

their work.15 Essentially, Weisel was looking to breathe new life into an industry that he felt was starved

for entrepreneurialism. So, three months after he split with NationsBank, Weisel opened Thomas Weisel

Partners (TWP), a boutique firm concentrated on the telecom and technology sectors, just a few blocks

away from NationsBanc Montgomery’s San Francisco offices. More than 150 of his former employees left

NationsBanc Montgomery to join him there.

3 thomas weisel partners

Some observers thought it was a bold move to start a small, focused firm in an era of financial services

conglomerates.16 But people close to Weisel say he has never been one to shirk risk if he believes the

rewards can be great enough. In founding TWP, Weisel reversed his earlier thinking from when he sold

Montgomery to NationsBank, now believing that there was a place for a small investment bank that

focused on growth companies, even if it lacked the huge pools of capital that the megabanks had at their

disposal.17 He envisioned TWP as a full-service merchant bank (which invests its own money in addition

to raising capital for other companies) with an entrepreneurial spirit that catered to entrepreneurial

companies.

Weisel thought his company - albeit a small West Coast start-up - would be attractive to people who

wanted to challenge the established firms in a free-thinking environment.18 TWP would be built upon

three pillars: investment banking, brokerage, and asset management, with an emphasis on the technology

sector. The three business divisions would be integrated, with employees in each area reaching across the

boundaries of their businesses to work together as a team.

“To Thom’s credit, he really saw at that time the inherent value of creating a private equity or an asset

management business within the context of what we did day-to-day,” said David Grossman, a former

Montgomery research analyst who followed Weisel to TWP. “That vision of integrating the private equity

activities with the investment bank and the broker-dealer was implemented from the very beginning, and

it became the fabric around which the firm was built.”

Weisel tapped into his broad network of West Coast venture capitalists and found 22 VC’s - including

many prominent Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and major venture capital firms – who were willing to

invest $35 million in TWP for a seven-percent stake in the firm, bringing TWP’s total valuation to $500

million.19 Weisel also sought seasoned directors and advisors for an outside advisory council he called the

CEO Founder’s Circle. He brought many influential businessmen and politicians onboard for the

Founder’s Circle, including Yahoo! CEO Tim Koogle and former U.S. congressman and vice presidential

candidate Jack Kemp. The members of the Founder’s Circle collectively invested $120 million in one of

TWP’s venture capital funds and provided guidance to Weisel and his executive committee.20 Weisel

noted:

Each investor put up a million or a million-and-a-half. These were guys who were running

billion-dollar funds. They really wanted to support somebody who was going to be focused and

help their kind of company. I don’t think any of them were saying, “Geez, we’re going to make a

lot of money on this thing,” since the valuation was $500 million on Day 1. So, they had to

swallow pretty hard on the price on Day 1, but they wanted to help support a firm that was

focused exclusively on the kind of things that they did.

Weisel recruited 53 partners who contributed $30 million to his new business venture in return for

ownership stakes in the company. The partners at TWP made less money than they would have made

working for a larger firm, but partnering with Weisel provided an opportunity to share in the profits of

what they hoped would be a rapidly rising firm.21 Weisel had an impressive track record at Montgomery,

producing nearly $2.5 billion for the partners there during the 1990s.22 In addition, Weisel was offering

them the chance to do exciting work at TWP. “We were offering almost no money, but we have a

partnership culture that is extremely attractive to entrepreneurial people,” Weisel explained.23 Using this

pitch, Weisel hired stars away from firms like Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley and Salomon Brothers.

Gordon Hodge, a founding partner at TWP who came from Montgomery, noted:

It was important for me to be a founding partner because I thought that, if this works, I’d love to

say I was there at the beginning. The opportunity to go work for a bulge-bracket firm, or another

firm offering another package was there, but it just wasn’t as interesting as the wealth creation

opportunity here, and the notion of coming in everyday as an underdog with a really good story

to tell and a really good shot at winning.

4 thomas weisel partners

At TWP, the compensation process was meant to reinforce the entrepreneurial spirit of the firm. Weisel

and his executive committee determined the partners’ compensation based on the percentage of their

equity stake, the firm’s annual performance, and the individual performance of each partner. Weisel

noted:

We redid the partnership and the equity stake every year, and it kind of put a gun to

everybody’s head that you had to keep performing. If you were a one-percent partner and you

didn’t perform as well as you should have, you might be reduced to a half-percent partner, or if

you were at a half-percent and you did well, you might go to a full-percent partner.

TWP’s CFO and COO David Baylor, who worked for Weisel for six years before joining him at TWP as a

founding partner, noted:

Thom gives people a lot of opportunity. He’s very hard to please, but at the same time he gives

the people who work for him as much opportunity as is reasonably possible, and if you can

handle it, he’ll give you more opportunities. I don’t think that anyone who works for Thom

feels like they are limited by their job description.

TWP’s head sales trader, Tony Stais, came to TWP from Goldman Sachs because of the opportunity to

work with Weisel in a partnership with an ownership culture. “It was challenging and kind of fun to go to

a place where you knew you could really have a big impact on the organization just by being there,” he

noted. Stais also said that he appreciated the sense of status that Weisel created for the partners. Weisel

hired a top chef from an upscale New York City restaurant to prepare meals for the Partners’ Dining

Room, an exclusive club at TWP headquarters in San Francisco that was reserved strictly for partners and

their guests. He also held off-site business retreats for the partners and their spouses where they could

socialize and as Stais put it, “let your hair down a bit.” “Thom really wanted to capture the essence of

status,” Stais said. “He spent a lot of time on that in the early years.”

Weisel certainly expected a great deal from the partners when the firm opened for business in January

1999. TWP’s business plan called for revenues of $96 million the first year, $272 million in 2000 and

$569 million by 2003.24 Weisel aimed to meet the financial projections by focusing the firm on investment

banking, research, institutional brokerage and private equity within key growth sectors of the economy:

consumer and business services, media and communications, healthcare, financial services, and

particularly, technology. The plan was risky, and while Weisel was optimistic about his firm’s future

performance, he wondered if TWP’s focus on specific growth sectors would limit the firm’s reach and

leave it vulnerable to a downturn in any one sector.25

TWP in the Technology Tailwind

The Internet boom was well underway when TWP opened for business, and Weisel was determined that

his firm would be the preeminent investment bank for technology related transactions. He believed that

change agents called “tailwinds” propelled certain markets along at a faster pace than the overall economy,

thereby producing new opportunities for investments.26 And in 1999, the Internet was producing one of

the fiercest tailwinds that the American economy – and Silicon Valley in particular - had ever seen.

The Internet boom began in 1995 with the IPO of California-based Netscape. The company hadn’t seen a

profitable quarter in the two years since its founding, and had actually lost $1.6 million on revenues of $12

million the quarter before it went public. Yet interest in the company was high since Netscape’s Internet

browser held 75 percent of the market, and many were hyping the company as “the next Microsoft.”

Underwriters Hambrecht & Quist and Morgan Stanley initially priced the offering at $14 a share, and

then bumped the price to $28 a share as investors expressed unusually strong interest in the offering.

During its first day of trading, Netscape’s stock soared to over $70 a share, and the company ended the

day with a market capitalization of more than $2.7 billion.27

5 thomas weisel partners

After the Netscape IPO, one small Internet-based company after another went to the public markets,

showing more in promise than in profits. Internet analysts extolled the dot-com market while investment

bankers raked in huge underwriting fees from taking Internet companies public. Many Internet

companies were able to realize tremendous valuations in short periods of time. For example, shares of

theglobe.com, brought public by Bear Stearns, rose a whopping 606 percent on the first day of trading in

November 1998.28

With Weisel’s deep understanding of both the entrepreneurs and venture capitalists of Silicon Valley,

TWP was well-positioned to capitalize on the Internet and technology boom. During its first year, TWP

orchestrated Yahoo!’s $3.6 billion stock acquisition of GeoCities and played a role in the IPOs of

Drugstore.com, Fogdog, FTD.com, InfoSpace.com, MapQuest.com, Netcentives, Red Hat, Scient,

Stamps.com, and TheStreet.com. As author Richard L. Brandt stated in his authorized biography of

Weisel, “TWP became an extraordinarily hot IPO machine.” 29

By the end of 1999, TWP had taken in $186 million in net revenues and had completed 108 transactions,

including 53 IPOs, 26 secondary offerings, 11 private placements, 14 M&A deals and two convertible

offerings collectively worth $23 billion.30 The following year, the firm’s revenues skyrocketed to $476

million and the media was extolling TWP as one of the fastest growing investment banks in history.31 In

addition to its Bay-area headquarters, TWP opened offices in Boston, London and New York, and

expanded its staff from 200 to nearly 800 people. Observers noted that Weisel appeared to have pulled off

the comeback of the century while NationsBank (by then renamed Banc of America Securities) had

virtually disappeared from the technology investment banking scene.32 Commenting on TWP’s success at

the time, Weisel, who was named “Banker of the Year” by Investment Dealers’ Digest in 2000, noted:

Our progress has been ahead of plan. We have been fortunate to benefit from excellent market

conditions but the strong results also speak to the soundness of our business strategy and the

quality of our people. There is enormous demand among growth companies and investors for a

firm that is solely focused on the new frontiers of the U.S. economy. We’ve been able to meet

this need with people who truly understand the forces – tailwinds as we call them - that are

transforming the economy and the way business is conducted. Our strategy of structuring the

entire resources of the firm around the tailwinds to harness their power for our clients is paying

dividends.”33

The partners were paid well during TWP’s first two years, although their compensation was still

considered low by industry standards.

In addition to chasing deals, TWP was building up its capital reserves. In January, 2000, Weisel brokered

a multi-million dollar deal with pension fund giant CalPERS (California Public Employees Retirement

System). CalPERS agreed to invest $100 million in TWP in exchange for a 10 percent stake in the firm.

Weisel said that CalPERS also promised to invest an additional $1 billion in TWP’s private equity

business.

In 2001, Weisel secured a $200 million commitment from Nomura Holdings Inc., the parent company of

the largest securities firm in Japan. Nomura agreed to invest $75 million directly in TWP for a 3.75percent stake. Nomura also allocated $125 million for TWP’s private equity funds, and pledged to help

raise an additional $500 million for the funds.34

6 thomas weisel partners

Silicon Valley's 1929

The Bubble Burst

From the outset of the Internet boom in 1995, market observers had been warning that the surge was

nothing more than a bubble that would soon pop. As early as 1996, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan

Greenspan had been describing the stock market’s valuations as “irrational exuberance.” The Dow Jones

News Service in 1998 declared “The End of the IPO” after observing that the market prices of newly

issued stocks were falling well below their offering prices.35

But for all of the nay-saying, the market remained robust. Venture capitalists continued to fund the early

growth of edgy, emerging companies, and investment bankers were finding plenty of willing takers for

the stock of businesses that had no history of earnings. Some analysts began to devise new metrics,

proclaiming a “new economy” that rendered older techniques of valuation obsolete. As one author

observed, “It’s now difficult to recall the environment and the reasons for the exuberance, but in the midst

of the excitement, it was difficult not to get caught up in the movement. It gained momentum like a

36

snowball rolling downhill, growing fat with new believers as it sped toward the abyss.”

Beginning in March of 2000, the air started leaking from the Internet bubble. Initially, the downturn in

the markets was labeled a brief correction. The venture capitalists and dot-com companies continued to

spend and plan as if the capital would keep flowing forever. 37 But as the market continued the spiral

downward and it became clear that many of the dot-coms would never make a profit, investors began to

realize that the Internet boom was over. Even healthy companies that relied on business from dot-coms

began to feel the pinch as they saw their revenues dive. Of the 1,262 companies that went public from

1998-2000, 12 percent had shares that were trading for less than $1 by the second quarter of 2001. Shares

of theglobe.com were trading at less than a quarter, and Merrill Lynch saw one of its dot-com gems,

Pets.com, go bankrupt just nine months after taking the company public.38

TWP, which focused its investment banking efforts exclusively on technology companies, saw a third of

the companies it took public during that time period go sour, their stock either delisted or their shares

trading for less than $1. Weisel recalled that this was one time when his instincts failed him. He did not

foresee a market collapse as severe as the decimation of the dot-com industry, and hindsight has shown

him that his firm was too heavily concentrated on technology. Weisel noted:

That part of the cycle, where you had a huge bubble and it came crashing down, was our 1929. I

don’t think anyone has seen an implosion of the global telecom industry and its infrastructure

the likes of which both that industry and the feeder system - the capital markets – went

through. It wasn’t like before when you had recessions. This was much more protracted and

deep. It’s taken a long time to reconstruct the venture capital community and the

entrepreneurial community that came out of that time period.

Weisel’s success at fundraising had provided a cushion for the firm during a time when business was

down overall. The firm had $240 million in equity capital (the amount raised from investors), including

about $100 million in cash.39 He noted:

The saving grace was that we raised a lot more capital than we needed, and it acted as a real

buffer. So at our lowest point, we lost $14 million on an operating basis. We had restructuring

fees, and we had to write off a lot of real estate. We were really lucky that our balance sheet

absorbed most of that, and that we had raised a lot of capital when we really didn’t need it.

7 thomas weisel partners

TWP’s Response

By mid-2001, the market for IPOs was all but dead. Only 21 IPOs valued at $7.97 billion went through

during the first half of the year, compared with 143 valued at $27.3 billion for the same time period in

2000.40 TWP completed 52 investment banking transactions in 2001, compared with the 138 deals it

brokered in 2000. The firm’s revenues dropped 30 percent in 2001 to $323 million, and fell another 20

percent in 2002.41

Business prospects for Weisel’s small, tech-focused firm had significantly dwindled. The dollar volume of

IPOs by technology companies had dropped 95 percent, from $64.6 billion in 2000 to $3 billion in 2002,

and the dollar volume of technology related mergers and acquisitions had dropped 91 percent, from $460

billion in 2000 to $42.5 billion in 2002.42

Weisel was in a tough bind. His firm was now overstaffed, and it was losing money. Operating costs

remained high, with compensation and benefits for TWP’s nearly 800 employees accounting for more

than half of the firm’s operating budget. The firm reduced its operating costs by 18 percent, or $67.1

million, from 2000-2002, and laid-off 300 people from 2000 through 2003. TWP’s investment banking

division went from 201 to 74 employees.43

Weisel trimmed his telecom and consumer dot-com workforce so he could redirect the firm’s focus by

hiring new people with expertise in areas other than technology. He recruited Mark Manson, a veteran

research analyst and senior manager at Donaldson, Lukfkin & Jenrette, and tasked him with reorganizing

TWP’s research department. Manson hired more analysts to cover healthcare, consumer businesses,

defense and environmental services, publishing, major pharmaceuticals, and the food and beverage

industry.

“We got sucked up in the tech bubble,” Weisel acknowledged. “We had to remake the organization.”44

Hodge, the founding partner who joined TWP from Montgomery, said that it was the sheer

determination to succeed that drove him and the other partners and employees forward during this

tumultuous time. Hodge, who works in equity research, noted:

What kept me motivated and excited was that still, at the very core, there was that

entrepreneurial opportunity and the core belief that we had a great brand and a great

opportunity as a firm to build a real franchise. We felt like partners, we felt like owners, we were

all in it together, and the good news was that we didn’t lose that entrepreneurial spirit, even

though our start-up phase was warped by our early success during the Internet bubble… Never

for a moment did we doubt that our firm had a great brand and a great group of people that on

any given day could go head-to-head with the best and the brightest in the investment

community. We had a differentiated product to offer our clients, so that sense of excellence and

that competitive fire, and the entrepreneurial spirit of the firm never diminished, and that’s

what kept a lot of us going.

Despite the economic downturn, TWP could still count on its downsized investment banking unit for

some revenues. The firm completed more than $1 billion in transactions and was the lead manager on 40

percent of its underwritings in 2002. TWP’s M&A advisory practice remained strong as the firm closed

such deals as the sale of Crossworlds Software to IBM, and the sale of eRoom to Documentum. However,

with the reduced deal flow, TWP began relying on its other two business lines - brokerage and asset

management - to provide more of the firm’s revenues. TWP’s brokerage business accounted for roughly

two-thirds of its revenues and continued to gain market share, with TWP moving 60 million shares a day

by October 2002, compared with its daily average of 22 million shares in 2000.45 The firm’s private equity

and asset management businesses managed $2.7 billion for clients.46

8 thomas weisel partners

By 2003, technology companies accounted for approximately 36 percent of TWP’s research portfolio,

down from 58 percent in 2000. The number of telecom companies covered dropped from 11 percent in

2000 to 3 percent by 2003.47 Analysts like Grossman had to quickly switch gears and develop expertise in

new coverage areas.

“I was a poster child for that era because my coverage universe focused almost exclusively on Internetrelated companies,” Grossman said. “With the burst of the Internet bubble, my coverage turned over

almost 100 percent. I went from covering small, hyper-growth companies to covering very mature, largecap companies that not only were relatively new to me, but were relatively new to our firm.”

Although the firm had refocused its sights within the capital markets, Weisel remained committed to

working with growth companies and venture capitalists. He noted:

The tech bubble blows up, and you have these tech companies that were tech companies, and

now they’re energy companies. They’ve completely remade themselves. We would never do

that. Even in the darkest of the dark times, we kept the vision.

The Partners’ Investments

In remodeling TWP’s infrastructure and realigning its focus with the new market environment, Weisel

managed to keep his firm competitive in the marketplace. Revenues were up slightly in 2003 and 2004

($249.3 million and $265.5 million respectively) but overall the firm was losing money. TWP recorded net

losses of $57.9 million in 2002, and $14.2 million for the first three quarters of 2005.48

The partners were not seeing the huge payouts they had anticipated when they signed on with TWP.

Many of the partners had financed their initial investments through bank loans that continued to require

interest payments while the book value of the investments continued to decline. By industry standards,

they were living on low salaries, and some of the junior partners were having a tough time making ends

meet in pricey San Francisco.

“However attractive a partnership structure was, when you’re a partner living off of income, and there

isn’t any income, what do you do?” said Manson, the research director who had joined TWP as a partner

in 2001. “And instead of it being one quarter every 27 years, it became a little more frequent than that.”

Weisel noted:

Normally, you have an overhead structure that’s like an accordion. About 50-80 percent of the

expenses are compensation. So, it can expand and contract greatly, and that kind of financial

structure works well, and it served us well at Montgomery. However, at TWP we went through

really testing times. In roughly a year, I had a company of 800 people. Our first full year, we had

done $500 million in revenue. That was the fastest start-up in the history of the financial

services industry. And so, when we were at $500 million, we thought we were going to $1

billion. That’s why we hired so many people. Instead, our revenues dropped to $250 million in

two years.

Perks like the Partners’ Dining Room ceased, and the off-site business retreats that the partners had

enjoyed during the firm’s first few years were replaced by business meetings at TWP headquarters in San

Francisco.

“That’s an aspect of the culture that didn’t endure,” Stais said of the partnership perks. “There was a

consensus among the partners that they were much more focused on their work, and that the social

aspects were superfluous. When it comes down to it, we’re all business people, and it’s all about the

financial results.”

9 thomas weisel partners

TWP lost a few partners during the lean years of 2001-2005. But most of the partners understood that the

industry was cyclical, that along with the ups there would inevitably be some downs.

“If the firm doesn’t make money, the partners don’t make money,” Stais explained. “There’s a risk-reward

trade-off there. Most partners understood that when they joined, but five years into it, they experienced

it. Some had the fortitude and the patience to stick it out, and some did not.”

Weisel recognized that compensation was an issue, but he thought of his business as a marathon, not a

sprint, and he expected his partners to emulate his winning attitude and stay the course.

“People are making less money now, but that shakes out the people who really didn’t have the long-term

interest and passion for the business,” Weisel said.49

Like Weisel, the majority of the firm’s partners remained hopeful for a recovery. But public perceptions of

TWP centered on the firm’s uncertain future, and rumors of bankruptcy or the disbanding of the

partnership began to circulate.

Toward the end of 2004, some of the partners began questioning if TWP’s partnership structure, which

had proved lucrative for Weisel and his partners during the 1980s and 90s, had become obsolete, or at

least less affective. In addition, TWP’s financial condition was deteriorating. In 2004, the firm was hit by

an extraordinary and unforeseen loss when the SEC fined TWP $12.5 million as part of a broader

settlement with mostly larger banks. The partners took a direct hit from the SEC’s action, as TWP paid

the fine with money from individual capital accounts instead of drawing from corporate coffers like the

bigger banks did.

TWP was also preparing for another potential hit to its balance sheet from the CalPERS and Nomura

investments. CalPERS and Nomura collectively held $175 million in convertible preferred stock - an

equity security that may be cashed in at face value or for the value of the investor’s original equity stake, or

exchanged for common stock at the investor’s discretion for a specified price. Convertible preferred stock

carries certain debt characteristics in that investors who hold the security may redeem it for face value

even if the face value is higher than what the stock is currently worth.

Nomura at the time of its initial investment had the right to exchange its convertible preferred stock for

$75 million, or 3.75 percent of the firm. Depending upon the fluctuations in the firm’s valuations, the

value of 3.75 percent might be greater or less than $75 million. So, when TWP’s revenues dropped to $250

million, the face value of Nomura’s convertible preferred stock at $75 million exceeded the value of its 3.75

percent equity stake. Could the firm’s balance sheet withstand a payout that equaled the face value of

CalPERS and Nomura’s collective equity?

TWP’s Renaissance

A Strategic Planning Proposal

Some of the partners felt that TWP faced three strategic choices: the firm could continue as it was,

downsize, or recapitalize and grow. Staying the course might result in a slow but steady downward spiral.

Downsizing would involve more lay-offs and the inevitable elimination of certain business functions. On

the other hand, recapitalization and rebuilding could bring expansion of the firm’s existing business lines,

and possibly, entrance into new business areas.

As a private company, TWP could pursue capital by seeking additional outside investments, like the

CalPERS and Nomura commitments, or it could sell securities through private placements under

10 thomas weisel partners

Regulation D of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1933 that could then be followed by SEC Rule

144/144A equity offerings.

Weisel noted that raising money as a private partnership is a long and difficult process. Relationships

with outside investors must be cultivated and nurtured, and big deals like the ones he brokered with

CalPERS and Nomura often take months and sometimes years to complete. Private placements followed

by 144/144A offerings are time-consuming and include numerous provisions, including restrictions on the

1

type of investor to whom the securities may be sold. However, some of the partners argued that while

these options might help TWP to stay afloat, what the firm really needed was a major infusion of capital

all at once. They suggested an action that, in their opinion, would fulfill the firm’s immediate need for

capital and strengthen its prospects for long-term growth: an initial public offering.

The decision to proceed with an IPO was clearly not a call to be made overnight. With the support of

Weisel and the members of the executive committee, Manson assembled an IPO Committee in January

2005 to study and conduct due diligence around the possibility of a public equity offering, and ultimately

to issue a recommendation to the executive committee.

The IPO Committee - Flushing out the Issues

Some of the partners thought that an IPO offered the highest probability of retaining and rewarding

TWP’s existing workforce, and it afforded opportunities for financial growth and raising capital through

subsequent equity offerings. While none of the boutique investment banks had gone public, a good

number of the larger banks had, and the partners were confident that TWP could break through the size

barrier and complete a successful IPO.

From a regulatory standpoint, an IPO would bolster TWP’s ability to do more and larger transactions,

and it would fund new initiatives to grow the business. It also might allow TWP to restructure its

relationships with financial partners like CalPERS and Nomura.

But there were some potential downsides too. The energy required to raise capital and communicate with

new or public investors might distract senior management from the firm’s daily operations. Public

companies must issue quarterly earnings reports, hold quarterly earnings calls with investors, and file

numerous documents (like 8K’s and 10K’s) with the SEC.

1

Regulation D of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1933 exempts registration requirements for private placements of securities by a corporation

if certain conditions are met. The issuing corporation must evaluate potential buyers and have reason to believe that those buyers are

sophisticated investors who understand enough about investing to evaluate potential investment risks. The issuing corporation must also give

potential buyers an offering memorandum that includes same information that would be available in prospectus of a public offering of securities,

and the issuing corporation in turn must secure an investment letter from the buyer stating that the buyer does not intend to immediately sell the

securities. Lastly, the issuing corporation is prohibited from selling securities to more than 35 non-accredited investors, or investors with a net

worth of less than $1 million and a gross income of less than $200,000. There is no limit on the number of accredited investors who may purchase

securities in a Regulation D private placement.

SEC Rule 144 deals with the sale of restricted and control stock. Restricted stock is not registered and is typically acquired through a private

placement. Control stock is acquired by affiliated people or insiders, such as officers or directors of a company. Both restricted and control stock

must be sold according to the provisions of Rule 144, which mandates a one-year holding period for restricted stock but not for control stock. The

rule also limits the number of restricted or control shares that can be sold over any 90-day period; for stock listed on an exchange and for Nasdaq

stock, the maximum amount that can be sold is the greater of one percent of the company’s total outstanding shares, or the stock’s average weekly

trading volume for the previous four weeks. Rule 144A exempts qualified institutional buyers (defined by the SEC as financial institutions with at

least $100 million invested in securities of issuers that are not affiliated with the corporation) from these requirements.

11 thomas weisel partners

The firm’s legal and compliance requirements would burgeon, requiring more of the firm’s resources and

energy to comply with the litany of rules and regulations of the Securities and Exchange Commission and

the various self-regulatory organizations (NASD, NYSE, MSRB) that govern the financial services

industry. The transformation from private partnership to public corporation also would require increased

transparency, as the firm would be required to publicize its historical and ongoing financial performance.

The IPO committee members met for several months to discuss the pros and cons of an IPO, both for the

firm as a whole and for the employees as individual professionals. They tried to use the process as a way

to flush out the issues, and align the workforce and the firm with a common goal. Stais, the head sales

trader and a member of the IPO committee, noted:

We were trying to get our arms around the potential benefits and the risks of changing from a

private partnership to a public company. We tried to identify why people liked working at the

firm, and also what the common grievances were. One thing that was not going to change was

Thom. He has a very strong personality, and people identify him as the one who sets the tone

for the firm.

The committee was broken down into focus groups whose members studied specific aspects of the IPO,

such as the financials of an IPO, the potential impact upon TWP’s culture, and the perception, both

internally and externally, of TWP as a viable public company.

Weisel said that one of his biggest concerns was how being a public company would affect TWP’s unique,

entrepreneurial culture. Would becoming a public company make TWP overly bureaucratic? Would the

firm become what Weisel loathed - a deal machine cranking out transaction after transaction to boost

revenues for investors demanding short-term results? Would there be an incentive for junior and senior

employees to work hard if the compensation structure changed and the allure of the elite partnership

circle no longer existed?

Stais, who was charged with studying the cultural aspect, explained:

From a financial standpoint, the decision to go for an IPO was a fairly easy argument to make.

But from a cultural standpoint, it was a little bit different because we had to reorient the

employees. The goal of the non-partners was to make partner. You would be promoted at the

end of the year, and invited into the partnership circle. It was an honor for people, and it was a

professional accomplishment in addition to being a financial accomplishment. If we decided to

go public, the incentive system that was motivating our best-performing people at the nonpartner level was effectively going to change dramatically. It was a big risk to take that away.

As a public company, the compensation structure of TWP would be drastically different. Instead of the

executive committee determining each partner’s performance-based equity stake on an annual basis,

employees would receive stock, or stock surrogates in the form of restricted stock units (“RSU’s”) that

would vest over a period of four years.

While stock or stock surrogates can be lucrative if the firm succeeds, they spread equity ownership among

hundreds of employees rather than a few dozen partners and provide less incentive if the stock declines.

“Being a partner with a huge financial stake versus being a shareholder with stock made the idea of an

IPO less attractive at the margin,” Stais explained. “The RSU’s that people would receive would not

compensate for the loss of the big bucks that partners stood to make from the partnership’s compensation

structure,” Manson noted.

Weisel feared that changing the compensation structure would hurt retention, especially among the senior

partners. As a partnership, the partners were motivated to perform and excel because their paychecks and

bonuses depended, in part, on how well they performed as individuals. Weisel wanted to keep his

employees highly motivated, and he wondered how that would change if the high-roller private

12 thomas weisel partners

partnership structure morphed into a fiscally conservative public company. He was concerned that he

would lose valuable employees to early retirement or to other firms offering better compensation

packages. Weisel noted:

One of biggest assets that we had as a private partnership was the ability to change the equity

ownership of the firm at the end of every year. When you go public, that changes, and

everyone’s stuck with what they’ve got. People who leave still own their stock as long as they

don’t go to work for a competitor for a year, although they don’t have access to the money until

their stock is fully vested. But, they can still retire at the beach and keep everything that they

own, and that was a concern for me. That was the biggest negative to going public, and it was

my biggest worry.

While the committee was comprised entirely of partners, Grossman, the research analyst who served on

the IPO Committee, said its members spent a lot of time discussing how an IPO would impact the nonpartners as well. The committee discussed how the firm, prior to an IPO, could compensate the nonpartners who were on the cusp of making partner. But issuing more equity as a private partnership would

have to be done carefully because of accounting, dilution and other factors. It was decided that TWP

needed to find a form of equity other than partnership stock to boost employee compensation. “There was

a lot of discussion about how we could make this an exciting and meaningful event not only for the

partners, but also for the people who were going to help sustain and grow the firm over the next 10

years,” Grossman said.

The Decision Point

While Weisel and the members of the IPO Committee raised valid concerns regarding real and pressing

issues, in the end, they agreed it was all about the financials. An IPO would give TWP the infusion of

capital it needed, and the partners would have a security that could be valued in the public stock market.

“Realistically speaking, given the economic situation that we were facing, the IPO was the next step that

we needed to take, regardless of the steps that we took after that,” said Baylor, TWP’s COO and CFO. “It

was really the only mechanism, and the only transaction with which we could affect the restructuring and

the capital raising in an advantageous way.”

An IPO could also give TWP a way out of its obligations to repay CalPERS and Nomura in full for their

investments.

“Both CalPERS and Nomura had potential put rights to us,” Weisel explained. “They had preferences, as

did the original investors. Part of the trick was to get rid of those put rights and those preferences through

an IPO, and convert those preferences to common stock.”

Stais said the IPO Committee also concluded that an IPO could have a positive affect on retention among

junior employees, and could strengthen the firm’s culture by doing away with the partnership hierarchy.

He noted:

One of the things we spent a lot of time talking about is how do we as a firm define ourselves,

and how do we define what our mission statement is. The culture here was in its very early

stages of development. People were open to suggestions about how to make things better, but

there really wasn’t an established set of goals and protocol of things we wanted to accomplish.

We felt that it would be easier to motivate people if the goals were clear. If the employees

worked hard and performed well, they could all be shareholders. We would all live and die by

the results… The firm’s operations would be more transparent, which had a downside. If you

have a bad day, or a bad week, then everyone knows about it. If the stock went down, the

employees would have public reminder that they were worse off than they were six months ago.

But in the end, we were willing to take that risk.

13 thomas weisel partners

The IPO Committee presented its findings to Weisel and the executive committee at the end of April

2005. A few months later, TWP hired investment banking powerhouse Goldman Sachs to serve as co-lead

manager of its IPO.

Going Public

Prior to 2005, market conditions would have made an IPO nearly impossible. But in 2005, the market was

improving, and there were more IPOs than the industry had seen from 2001-2004 combined. While

companies weren’t going public in records numbers as they did during the 1990s, the fact that IPOs were

experiencing a comeback was an encouraging sign.

TWP filed its prospectus with the SEC on Oct. 19, 2005 with Goldman and TWP as the lead managers,

and Keefe, Bruyette & Woods as co-manager. However, Goldman advised TWP to delay the IPO because

TWP had recorded a net loss of $14.2 million for the first three quarters of 2005, which was the second

largest net loss for TWP since its founding. Rather than waiting for Goldman to be ready, TWP decided

to proceed with the IPO as planned.

The firm filed a new prospectus with the SEC on Feb. 2, 2006, listing itself and Keefe, Bruyette & Woods

as joint book-running managers, with Fox-Pitt, Kelton as the co-manager. In total, TWP was offering 6

million shares of common stock at $13-$15 per share, with the company selling 4,783,670 shares and

existing stockholders putting up 1,216,330 shares. In addition to the issued stock, TWP would have

22,130,940 shares of outstanding stock.50

Upon completion of the offering, the partners would collectively own 55.9 percent of the outstanding

stock. Weisel would own 12 percent of the common stock, and the five other members of TWP’s executive

committee would own 24.2 percent of the common stock. These shareholdings would allow TWP and its

partners to retain control of the company.51

Weisel and Baylor got CalPERS and Nomura to agree to accept repayment of 40 cents on the dollar for

the amount they had invested in TWP. CalPERS decided to convert its shares of preferred stock to sell as

common stock in the IPO, and exit its relationship with TWP entirely. Nomura, on the other hand, was

interested in maintaining and strengthening its ties with TWP. As part of the IPO, TWP would issue a

2

warrant to Nomura at a fair value of $4.6 million. In the weeks leading up to TWP’s IPO, media articles

expressed skepticism about how well the stock would perform. Many took Goldman’s exit as a bad sign.

But TWP was fully subscribed at $15 a share, and on its first day of trading, TWP’s stock price rose 30

percent. The firm ended the day with a market capitalization of approximately $475 million.

TWP took in $62.3 million in net proceeds from its IPO. Three months later, TWP did a secondary

offering at $22 per share that injected an additional $100 million into the firm’s balance sheet. The

executive committee allowed the partners to sell up to 20 percent of their holdings in the secondary

offering, which allowed TWP’s partners to repay the debt that they had incurred through their initial

investments in TWP while maintaining 80 percent of their ownership in the firm. Weisel explained:

The secondary was a big liquidity event for a number of the partners, but it also raised $100

million of extra money for the firm. So there was money for the firm and money for the

partners. I didn’t sell any shares, but most of the partners sold a 20-percent stake on an after-tax

basis, which basically equaled the amount they had borrowed to put capital into the firm in the

first place… Essentially, we took a $220 million liability and in three months, with an IPO and a

2

Warrants resemble stock options because they give the purchaser the option of buying common stock at a specified price in the future. The fair

value of Nomura’s warrant was determined by applying the Black-Scholes option pricing model using an exercise price based on the initial public

offering price of $15 per share.

14 thomas weisel partners

secondary offering, transformed it to $200 million in cash on our balance sheet and the partners

kept 80 percent of their position in the company.

With the IPO completed, the $200 million question for Weisel and his executive committee was how to

best put the firm’s newfound capital to use. Should the firm invest its new capital by:

•

building on its existing strengths in brokerage, underwriting and advisory by hiring more senior

analysts, traders or bankers in its core franchises of technology, healthcare and consumer

businesses?

•

expanding the number of sectors that it was addressing by adding new verticals like energy or

financial services?

•

re-establishing a foreign capability in London, Indian or elsewhere.

•

developing new product capacity, like derivatives in brokerage or debt issuance in investment

banking or a totally new business like municipal bonds?

•

rebuilding its money management business in venture capital, private equity or the management

of publicly traded stocks for institutions or through mutual funds?

In any of these choices, TWP would need to make a “build-versus-buy” decision and would be influenced

in those decisions to maintain compensation at no more than 55 percent of revenues. Or, in light of rapidly

rising prices for labor and for niche acquisitions that were being inflated by a rapidly accelerating bull

market, should TWP bide its time and wait for prices to come down? The IPO had repaired a host of

problems but a series of demanding and critical decisions still lay ahead.

This case has been developed with the cooperation of Thomas Weisel Partners for pedagogical purposes. The case is not intended

to furnish primary data, serve as an endorsement of the organization in question, or illustrate either effective or ineffective

management techniques or strategies.

Copyright 2007 © Yale University. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of Yale University School of Management. To

order copies of this material or to receive permission to reprint any or all of this document, please contact the Yale SOM Case

Study Research Team, PO Box 208200, New Haven, CT 06520.

Endnotes

1

Case Writer, Yale School of Management

2

Distinguished Faculty Fellow, Yale School of Management

3

Director of Case Study Research, Yale School of Management

4

Richard L. Brandt & Thomas W. Weisel, Capital Instincts: Life as a Financier, Entrepreneur and Athlete, p. 27. ©

2003 by Richard L. Brandt and Thomas W. Weisel, published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, N.J.

5

Brandt & Weisel, p. 58.

6

Brandt & Weisel, p. 60-61.

15 thomas weisel partners

7

Scott McMurray, “What Makes Montgomery Run?” Institutional Investor, Feb. 1, 1997, Vol. 31, No. 2, p. 46.

8

Brandt & Weisel, p. 58-59.

9

McMurray, 46.

10

Thomas Delong and Ashish Nanda, Harvard Business School Case Study 9-800-215, Thomas Weisel Partners (A),

2000.

11

HBS Case Study (A).

12

Brandt & Weisel, p. 238-9.

13

HBS Case Study (A).

14

“Montgomery Securities Founder Quits,” Associated Press Newswires, Sept. 22, 1998.

15

HBS Case Study (A).

16

Brandt & Weisel, p. 251.

17

Brandt & Weisel, p. 252

18

HBS Case Study (A).

19

Brandt & Weisel p. 254.

20

Brandt & Weisel, p. 254.

21

Brandt & Weisel, p. 255.

22

Thomas Delong, Ashish Nanda and Scot Landry, HBS Case Study 9-800-331, Thomas Weisel Partners (B): Year

One, 2000.

23

HBS Case Study (B).

24

Brandt & Weisel, p. 256.

25

HBS Case Study (A).

26

Brandt & Weisel, p. 255.

27

Beppi Crosariol. “Netscape IPO booted up; Debut of hot stock stuns Wall Street veterans” The Boston Globe,

August 10, 1995, p. 37.

28

Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Just Who Brought Those Duds To Market?” The New York Times, April 15, 2001, p BU1.

29

Brandt & Weisel, p. 257.

30

Brandt & Weisel, p. 257.

31

Brandt & Weisel, p. 257.

32

Brand & Weisel, p. 258-9.

33

HBS Case Study (B).

34

Brandt & Weisel, p. 263.

35

Brandt & Weisel, p. 256.

36

Brandt & Weisel, p. 259.

37

Brandt & Weisel, p. 260.

38

Sorkin, p. BU1.

39

Brandt & Weisel, p. 263.

40

Sorkin, p. BU1.

41

Brandt & Weisel, p. 261.

16 thomas weisel partners

42

Thomas Weisel Partners prospectus, Feb. 2, 2006, p. 11.

43

TWP Prospectus, p. 45.

44

Brandt & Weisel, p. 262.

45

Brandt & Weisel, p. 263

46

Brandt & Weisel, p. 263.

47

Brandt & Weisel, p. 262.

48

TWP Prospectus, p. 15.

49

Brandt & Weisel, p. 265.

50

TWP prospectus, p. 21.

51

TWP prospectus, p. 21.

17 thomas weisel partners

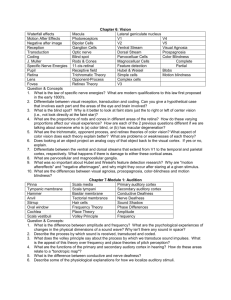

Exhibit 1: TWP Financials, 2000-2005

(in thousands, except selected data and ratios)

As of or for Nine Months

Ended September 30,

As of or for Year Ended December 31,

2000

2001

$ 266,244

211,906

(366)

20,463

$ 107,259

221,690

8,655

11,256

Total Revenue

Interest expense

498,247

(11,858)

348,860

(11,416)

249,319

(5,634)

265,519

(3,615)

286,880

(3,470)

212,847

(2,492)

180,799

(3,567)

Net Revenue

Expenses:

Compensation and benefits (a)

Other expenses and taxes

486,389

337,444

243,685

261,904

283,410

210,355

177,232

216,058

152,660

159,177

169,115

131,486

170,126

127,184

124,263

146,078

114,650

111,529

89,620

117,089

74,300

Total expenses and taxes

Net income (loss)(a)(b)

Less: Preferred dividends and accretion

368,718

117,671

(11,470)

328,292

9,152

(6,580)

301,612

(57,927)

(14,520)

251,447

10,457

(15,380)

260,728

22,682

(15,761)

201,149

9,206

(11,758)

191,389

(14,157)

(11,543)

Income (loss) attributable to

Class A, B and C shareholders (a)(b)

$ 106,201

$

2,572

$ (72,447)

$

$ 397,735

222,095

$ 480,164

271,927

$ 325,399

197,444

$ 312,606

182,721

139,470

36,170

209,378

(1,141)

214,070

(86,115)

216,624

(86,739)

Revenues

Investment banking

Borkerage

Asset Management

Interest income

Statement of Financial Condition Data:

Total assets

Total liabilities

Total redeemable convertible

preferred stock

Members' equity (deficit)

Selected Date and Ratios:

Investment Banking:

Number of transactions

Revenue per transaction

($ in millions)

Brokerage:

Average daily customer

trading volume (in millions)

Average net commission per share

Research:

Publishing analysts

Companies covered

Number of companies

covered per publishing analyst

Other:

Average number of employees

18 thomas weisel partners

134

2002

$

52

53,670

172,008

17,792

5,849

2003

$

42

82,414

139,391

41,598

2,116

(4,923)

2004

$

$

84,977

154,746

44,009

3,148

$

$

65,088

118,792

26,710

2,257

2005

$

(2,552)

$

$ 309,174

178,206

$ 314,023

194,294

$

221,635

(90,667)

220,320

(100,591)

62

6,921

2004

88

47,318

104,255

25,787

3,439

(25,700)

248,686

141,404

222,370

(115,088)

67

45

$

1.86

$

1.98

$

1.24

$

1.23

$

0.93

$

0.94

$

0.96

$

14.3

0.049

$

17.4

0.052

$

15.2

0.045

$

15.6

0.042

$

19.2

0.040

$

19.7

0.040

$

17.9

0.038

33

254

34

373

36

462

33

474

32

469

31

465

37

545

8

11

13

14

15

15

15

643

770

649

525

540

536

536

Exhibit 2: TWP Balance Sheet (in thousands)

December 31,

ASSETS

Cash and cash equivalents

Restricted cash and cash segregated under federal or other regulations

Securities owned — at market value

Receivable from clearing broker

Corporate finance and syndicate receivables (net of allowance for

doubtful accounts of $87 at September 30, 2005, $925 at December 31, 2004 and $925 at December 31, 2003)

Investments in partnerships and other securities

Furniture, equipment, and leasehold improvements — net of accumulated depreciation and amortization

Receivables from related parties (net of allowance for doubtful loans

of $3,528 at September 30,2005, $3,892 at December 31, 2004

and $4,208 at December 31, 2003)

Other assets

TOTAL ASSETS

September 30,

2003

2004

2005

$ 74,827

$ 57,993

$ 45,834

5,773

86,441

29,970

8,634

124,855

10,672

9,781

59,670

26,712

17,807

28,162

9,889

39,782

13,381

43,315

47,287

37,704

31,694

8,064

14,275

$ 312,606

6,213

13,432

$ 309,174

5,699

12,600

$ 248,686

$ 82,968

22,708

57,807

1,375

4,334

13,529

182,721

$ 78,242

35,162

44,734

3,732

2,502

13,834

178,206

$ 55,240

28,511

41,803

3,403

2,115

10,332

141,404

41,624

100,000

75,000

216,624

46,635

100,000

75,000

221,635

47,370

100,000

75,000

222,370

28,287

(114,730)

(296)

(86,739)

27,752

(118,122)

(297)

(90,667)

25,287

(140,063)

(312)

(115,088)

$ 312,606

$ 309,174

$ 248,686

LIABILITIES, REDEEMABLE CONVERTIBLE PREFERENCE

STOCK AND MEMBERS’ DEFICIT

LIABILITIES

Securities sold, but not yet purchased — at market value

Accrued compensation

Accrued expenses and other liabilities

Payable to customers

Capital lease obligations

Notes payable

Total liabilities

COMMITMENTS AND CONTINGENCIES

REDEEMABLE CONVERTIBLE PREFERENCE STOCK:

Class C redeemable preference shares

Class D redeemable convertible shares

Class D-1 redeemable convertible shares

Total redeemable convertible preference stock

MEMBERS’ DEFICIT:

Paid-in capital:

Class A shares

Accumulated deficit

Accumulated other comprehensive loss

Total members’ deficit

TOTAL LIABILITIES, REDEEMABLE CONVERTIBLE PREFERENCE STOCK AND MEMBERS’ DEFICIT

PRO FORMA, AS ADJUSTED (UNAUDITED)

Pro forma cash and cash equivalents

Pro forma deferred tax asset

Pro forma total assets

Pro forma capital lease obligations and notes payable

Pro forma total redeemable preference shares (classes C, D and D-1)

Pro forma paid-in capital Class A shares

Pro forma common stock, par value $0.01 per share

Pro forma additional paid-in capital

Pro forma accumulated deficit

Pro forma stockholders’ equity

19 thomas weisel partners

$ 43,564

10,326

256,742

45,061

—

—

173

198,800

(113,667)

84,994

Exhibit 3: Pro Forma Condensed Consolidated Statement of Financial Condition (in thousands except per share data; as of September 30, 2005)

Historical (as

restated)

Pro Forma Adjustments

for Compensation and

Corporate tax

Total Pro Forma, as Adjusted

for Compensation

and Corporate tax

Pro Forma

Adjustments for the

Reorganization

Total Pro Forma,

as Adjusted

$ 45,834

-

$ 45,834

$ (2,270)

$ 43,564

—

22,811

10,326

—

10,326

Other assets

202,852

(12,485)

—

202,852

—

202,852

Total assets

$ 248,686

$ 10,326

$ 259,012

$ (2,270)

256,742

$ 28,511

$—

$ 28,511

$—

$ 28,511

12,447

—

12,447

32,614

45,061

Cash and cash equivalents

Deferred tax asset

Compensation payable

Capital lease obligations & notes payable

Other liabilities

100,446

—

100,446

(2,270)

98,176

Total liabilities

141,404

—

141,404

30,344

171,748

Redeemable convertible preference stock

222,370

—

222,370

(206,300)

(16,070)

—

25,287

—

25,287

(25,287)

—

—

—

—

173

173

—

—

—

198,800

198,800

Members’ equity and stockholders’ equity:

Paid-in capital

Common stock, par value $0.01 per share

Additional paid-in capital

Accumulated other comprehensive loss

(312)

—

(312)

—

(312)

Accumulated deficit

(140,063)

22,811

(129,737)

16,070

(113,667)

Total members’ equity (deficit) and stockholders’ equity

(115,088)

(12,485)

10,326

(104,762)

189,756

84,994

Total liabilities, redeemable convertible preference stock,

members’ equity (deficit) and stockholders’ equity

Shares outstanding

$ 248,686

$ 10,326

$ 259,012

$ (2,270)

$ 256,742

Basic

Pro forma book value per share

20 thomas weisel partners

13,274

$ (7.89)

17,347

$ 4.90