THE ROLE OF PERSONALITY IN SATISFACTION WITH LIFE AND

advertisement

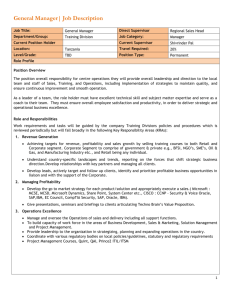

Behavioral Psychology / Psicología Conductual, Vol. 19, Nº 2, 2011, pp. 333-345 THE ROLE OF PERSONALITY IN SATISFACTION WITH LIFE AND SPORT1 Nicolas Baudin1, Anton Aluja2,3, Jean-Pierre Rolland1, and Angel Blanch2,3 1 Université Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense, France; 2University of Lleida; 3Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida (Spain) Abstract This study tested the relationships between personality, measured with the Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO-PI-R), satisfaction with life and satisfaction with sport, based on the five dimensions and on the thirty facets. Consistent with previous studies, satisfaction with life and satisfaction with sport were highly correlated. Stepwise regressions analysis showed that neuroticism and extraversion were the best predictors of life and sport satisfaction, bearing in mind that the other dimensions did not provide any prediction whatsoever. These results also indicated that a more precise facetbased assessment of personality significantly increased the prediction of satisfaction with life. The parametrical or graphical regression analysis LOESS revealed an interesting and different relationship between personality and satisfaction with life and sport. Key words: personality dimensions, personality facets, life satisfaction, sport satisfaction. Resumen Este estudio evaluó las relaciones entre la personalidad, medida por el “Inventario de personalidad, neuroticismo, extraversión y apertura, revisado” (Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Inventory-Revised NEO-PI-R), satisfacción con la vida y la satisfacción con el deporte, basándose en las cinco dimensiones y las treinta facetas. Siendo consistentes con estudios previos, la satisfacción con la vida y la satisfacción con el deporte tuvieron una alta correlación. Un análisis de regresión por pasos sucesivos mostró que el neuroticismo y la extraversión eran los mejores predictores de la satisfacción con la vida y con el deporte, teniendo en cuenta que las otras dimensiones no aportaron ninguna predicción. Estos resultados también indicaron que una valoración más precisa de Correspondence: Anton Aluja, Institut of Biomedical Research of Lleida, University of Lleida, Avd. Estudi General, 4, 25001 Lleida (Spain). E-mail: aluja@pip.udl.cat 334 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch la personalidad, con base en las facetas, aumentó la predicción en la satisfacción con la vida. Un análisis de regresión gráfica o paramétrico LOESS mostró una relación interesante y diferente entre la personalidad y la satisfacción con la vida y con el deporte. Palabras clave: dimensiones de personalidad, facetas de personalidad, satisfacción de vida, satisfacción deportiva. Introduction Psychology has focused for a long time on the association of the negative emotions with the distress of individuals (anxiety, depression…) while forgetting positive emotions such as happiness and satisfaction. For example, it has only been since 1973 that the International Psychological Abstracts introduced the key word “happiness” into its repertory (Diener, 1984). This tendency has changed and researchers have shifted their interest to the positive pole of human behaviour with happiness becoming a central topic. Over the past two decades research on the determinants of subjective wellbeing has increased dramatically (Diener, Suh, Lucas, & Smith, 1999) Researchers typically distinguish an affective component and a cognitive component of subjective wellbeing. The present article focuses on the cognitive component of subjective well-being, that is, people’s evaluations of their lives. This component of subjective well-being is typically assessed by life satisfaction judgments (e.g., ‘‘I am satisfied with my life’’; cf., Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985). After focusing on demographic factors such as health, income, educational context and marital status, which were showed to explain only a weak amount of the variance of life satisfaction (Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976) other works have demonstrated that levels of life satisfaction are stable over time and are often correlated with stable personality features (Diener, Oishi, & Lucas, 2003). While the first approach (situational) attempted to identify the external factors influencing life satisfaction including environmental or demographic factors, the second (personality traits) focused on the internal processes of the individual. This distinction gave rise to two hierarchical models of life satisfaction: the bottom-up and top-down models (Diener, 1984). The top-down approach defends the assumption that people have a stable predisposition to interpret life experiences. Individuals react to experiences either in a positive or in a negative way and this general tendency influences the evaluation of the various events occurring in a variety of life domains. According to the bottom-up theory, global feelings of well-being are the result of favorable events and living conditions. In other words, satisfaction and happiness are the result of a life containing numerous moments (or conditions) of happiness in a variety of realms: family, couple, incomes or work. In the late 1990s, a meta-analysis by DeNeve & Cooper (1998) highlighted the existence of a large number of works concerning the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. A recent study showed that previous Personality in life and sport satisfaction 335 research had underestimated the relationship between personality and subjective well-being, and established that total subjective well-being variance accounted for by personality can reach as high as 39% or 63%, corrected from the error of measure (Steel, Schmidt, & Shultz, 2008). In terms of the Big Five dimensions, the aforementioned study suggested that neuroticism and extraversion were the most important predictors of life satisfaction. McCrae & Costa, Jr. (1991) suggested that agreeableness and conscientiousness would increase the likelihood of positive experiences in social and achievement situations, respectively, and that they could be directly related to subjective well-being. Openness to experience should lead the person to experience both more positive and negative emotional states. In an integrative study on life satisfaction stability and the use of chronically accessible sources of judgement, Shimmack, Diener, & Oishi, (2002) showed that three dimensions of personality, extraversion, neuroticism and conscientiousness can explain 65% of the life satisfaction variance. Job satisfaction has been the most studied life satisfaction (LS) domain. The link between personality and job satisfaction was found to be the same as for life satisfaction. The main reason being that, work is a central life activity for most people explaining the strong link between job and life satisfaction (Dubin, 1956; Tait, Padgett, & Baldwin, 1989). A meta-analysis by Judge, Heller, & Mount (2002) suggested that correlations with job satisfaction were high and negative for neuroticism, high and positive for extraversion and conscientiousness and low and negative for openness to experience and agreeableness. Moreover, only the relationships of neuroticism and extraversion with job satisfaction generalized across studies. Personality traits showed a high correlation with job satisfaction, indicating support for the validity of the dispositional source of job satisfaction when traits are organized according to the five factor model of personality. Most of the studies assessed personality at the level of broad and global personality traits. However, as an intervening step toward explanatory research, it would be fruitful to consider more research between subjective well-being and personality at a facet level. We located only a few studies investigating subjective wellbeing at this level of precision, but the results were extremely promising (Steel et al., 2008). In a meta-analysis, Steel et al. showed that facet level analysis accounted for approximately twice the amount of variance than a trait level. At a facet level, the depression facet of neuroticism and the positive emotion facet of extraversion appeared to be the strongest and most consistent predictors of life satisfaction (Schimmack, Oishi, Furr, & Funder, 2004). Some studies indicated that life satisfaction could be viewed as the result of satisfaction with various life domains (Andrews & Withey, 1976; Campbell et al., 1976). This notion is based on the assumption that individuals evaluate the details of their life’s experiences when making overall satisfaction judgments (Rice, McFarlin, Hunt, & Near, 1985). Only a few studies have discussed about non-work life domains, even though equivalent linking mechanisms could apply to satisfaction with non-work life domains (Rode, 2004). Sport is a very important life domain and can be perceived as a non-work life satisfaction domain. Participation in sports and physical activity has received an increasing interest in our society where obesity and a sedentary 336 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch lifestyle have become more widespread (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). The study on the influence of dispositional variables in sport satisfaction and their link with life satisfaction might provide additional evidence for the predictive influence of personality on life satisfaction’s domains. In the sports literature, the subjective point of view of the athlete is largely ignored for the benefit of an objective evaluation of the performances or the physical and technical qualities. Other researches are based on the concept of achievement and the goal theory (Cindy & Koenraad, 2005) or study the motivation to engage and continue the activity like the “Satisfaction with the quality of the sporting experience” survey (S.Q.S.E) conducted by the English government. Some study tried to rely on cognitive process and created new measures like the Perception of Success Questionnaire (POSQ; Roberts, Treasure, & Balague, 1998), or the Satisfaction Interest Boredom Questionnaires (Duda & Nicholls, 1992) which were used in the sport domain. But all these researches are from different theoretical background and there is nothing like a clear definition of what sport satisfaction is and how to measure it. While it was the same in the work domain during several decades, researchers are giving a more central part to the individual subjective point of view by using the concept of job satisfaction and by studying the link with life satisfaction. Based on the works of Diener (1984) and Pavot & Diener (1993) we can define sport satisfaction as a cognitive judgment of an individual overall sports experiences in which the criteria are decided by the person herself. The aims of the present work were to study the relationship between personality and life and sport satisfaction at a facet level, in order to provide a more accurate description of these relationships and to compare whether NEO PI-R, at both the dimensions and facets levels, was a better predictor of life satisfaction or sport satisfaction. In accordance with past results (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), we hypothesised a positive relationship between neuroticism and extraversion, measured by the NEO PI-R, life satisfaction and sport satisfaction. Furthermore, the current work assessed differences in the personality profile in regard to life and sport satisfaction levels. Method Sample Participants were three hundred and thirteen French (231 men and 82 women) with ages ranging from 17 to 47 (M= 22.9, SD= 5.9) who volunteered to participate in the study. Participants were competitive athletes engaging in a collective sport activity (Handball, football, US football, rugby) three to five times a week, for one to thirty years. All of the participants compete on a regular basis (match every week end during the season) in different levels ranging from regional to international. No specific criteria were used for the sample construction other Personality in life and sport satisfaction 337 than a regular and competitive practice for more than two years. Participants completed the French language version of the satisfaction with life scale and the satisfaction with sport scale as well as a personality based measure. A trained interviewer collected the data on the training sites of all participants. Most of the required athletes participated in the study. Instruments 1. Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Questionnaire-Revised (NEO PI-R). The French version of the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) was used to measure the personality domains: neuroticism (N), extraversion (E), openness to experience (O), agreeableness (A), and conscientiousness (C), and their thirty facets. Subjects answer to the 240 items of the questionnaire on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0-4), ranging from” Strongly disagree” (0) to “Strongly agree” (4). Reliability coefficients (Cronbach alpha) ranged from 0.85 (agreeableness) to 0.92 (neuroticism) (Costa, McCrae, & Rolland, 1998). Spanish adaptation of the NEO-PI-R is published by Aluja, Blanch, Solé, Dolcet, & Gallart, S. (2009). 2. Satisfaction with life scale. The satisfaction with life scale (Pavot & Diener, 1993; Diener et al., 1985) was developed for the evaluation of general life satisfaction. Subjects responded to five affirmative sentences (“The conditions of my life are excellent”; “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”). The original study by Diener et al. (1985) found a reliability coefficient (Cronbach alpha) of 0.87. 3. Satisfaction with sport scale. The satisfaction with sport scale inventory was developed expressly for this study based on the satisfaction with life scale (Diener et al., 1985) for the evaluation of general sport satisfaction. This measure contains five items build in reference to the five items if the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985). Participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) their agreement with these five statements: “1. In most ways my sport life is close to my ideal; 2. The conditions of my sport life are excellent; 3. I am satisfied with my sport life; 4. So far I have gotten the important things I want in my sport life; 5. If I could live my sport life over, I would change almost nothing”. The satisfaction with sport scale is reliable (Cronbach alpha coefficient 0.76). Statistical Analyses To test the data, we used linear and graphical non-parametrical regression analyses. First, we conducted a series of stepwise regression analysis in which we set the inclusion criterion to p< 0.05 and the out criterion to p< 0.10. The relationships were analyzed through the LOESS, non-parametric, local area, polynomial regression procedure (Fan & Gijbels, 1996; Fox, 2000) to produce data 338 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch points for the NEO-PI-R dimensions lines that run the full length of the satisfaction continua. This procedure was recently used by Aluja, García, Cuevas, & García (2007) for predicting personality disorders from personality dimensions. Results Descriptive, correlations and internal consistence Table 1 shows descriptive distribution values and reliabilities for the Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Questionnaire-Revised, satisfaction with life scale and satisfaction with sport scale. Note that the kurtosis and skewness report a normal distribution for all scales (values between -1 and +1). Internal consistence alphas for the measures of personality, life satisfaction and sport satisfaction are correct and ranged from 0.64 to 0.85. The correlation between life satisfaction and sport satisfaction is positive. In this study, significant correlations were found between the NEO-PI-R, life satisfaction and sport satisfaction. Neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeability were correlated with life satisfaction while only neuroticism and extraversion were correlated with sport satisfaction. The analysis regarding the impact of age and gender, on life satisfaction and sport satisfaction were non-significant. Linear regression analysis To examine the unique contribution of personality dimensions and facets to life satisfaction and sport satisfaction, we conducted a series of independent stepwise regression analyses for the NEO PI-R dimensions and facets. Table 2 shows that for the dimensions, only neuroticism and extraversion were significant predictors of life and sport satisfaction. We can note here that neuroticism (b= -0.33) was the best predictor of life satisfaction while extraversion (b= 0.17) was the best for sport satisfaction. In another analysis, considering the relation between the facets and life satisfaction, vulnerability (b= -0.22), depression (b= -0.19) and positive emotions (b= 0.19) were the best predictors. For sport satisfaction, the positive emotions facets of extraversion was the higher predictor (b= 0.20) and only anxiety (b= -0.14) was also significant in this analysis. When all the facets and dimensions were included in the same analysis, the dimensions did not explain any additional variance in life satisfaction and the neuroticism dimension became the second predictor of sport satisfaction after the positive emotions facet. We also examined whether personality dimensions belonging to the other three dimensions of the NEO PI-R added to the prediction of satisfaction. Simple correlation (table 1) revealed some positive relation of conscientiousness with life satisfaction but conscientiousness as well as openness or agreeableness were not significant predictors in the regression analysis. 115.57 110.84 116.58 112.22 23.04 22.58 2. Extraversion 3. Openess 4. Agreeableness 5. Conscientiousness 6. Life satisfaction 7. Sport satisfaction *p< 0.05 ; **p< 0.01. 89.27 M 1. Neuroticism Variables 5.07 5.47 17.88 16.45 15.26 16.52 19.66 SD -0.14 0.09 0.31 0.78 0.13 -0.07 0.36 Kurtosis -0.45 -0.46 -0.41 -0.49 0.39 -0.14 0.24 Skewness 0.76 0.85 0.80 0.69 0.64 0.71 0.80 a -0.19** -0.39** -0.27** -0.09 0.18** -0.26** 1 0.21** 0.30** 0.23** 0.06 0.23** 2 -0.05 -0.05 0.04 0.10 3 Table 1 Descriptives statistics and bivariates correlations for observed indicators 0.03 0.12* 0.21** 4 0.07 0.20** 5 0.45** 6 Personality in life and sport satisfaction 339 340 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch Table 2 Stepwise regression between dimensions and facets of the NEOPI-R and life satisfaction and sport satisfaction Variables Life Satisfaction b R2 Sport Satisfaction b Neuroticism -0.33 Extraversion 0.22 N1 - Anxiety -- -0.14 N3 - Depression -0.19 -- N6 - Vulnerability -0.22 E6 - Positive emotions 0.19 A1 - Confiance 0.17 -- O4 - Actions -0.12 -- 0.20 0.27 -0.14 0.17 -0.20 R2 0.06 0.07 Non-parametrical graphical regression analysis (LOESS) Non-linear relationships were analyzed through the LOESS, non-parametric, local area, polynomial regression procedure (Aluja, García, Cuevas, & García, O, 2007; Fan & Gijbels, 1996; Fox, 2000) to produce data points for the NEO-PIR dimensions lines that run the full length of the Life and Sport Satisfaction continua. This method involves a series of local regression analyses that allow the shape of a curve to vary across the variable continua. For each specified neighbourhood of data points, a weighted least-squares regression is performed that fits linear or quadratic functions of the predictors at the centres of every neighborhood (O’Connor, 2005). The procedure produces a smoothed, nonlinear curve fit to the data which is analogous to the moving averages that are computed in time series analyses. NEOPI-R dimensions raw scores were transformed to z scores, whereas the two satisfaction scales were converted to T scores. Subjects with high life satisfaction presented a profile of low scores in neuroticism and high scores in agreeableness and extraversion. For sport satisfaction, the high score in extraversion was more important while the score in neuroticism was lower than for life satisfaction. We can also highlight that openness to experiences remained stable on the continuum of satisfaction which suggests that openness to experiences was not linked to any of the satisfaction scales (figure 1). Personality in life and sport satisfaction 341 Figure 1 Comparison of LOESS plot for NEO PI-R domains and life and sport satisfaction 342 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch Discussion This study intended to replicate the relations between the NEO-PI-R and life satisfaction obtained by previous research (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Shimmack et al., 2004; Steel et al., 2008) in a sport-oriented sample. According to Rojas (2006), there is a general consensus on the association between a person’s life satisfaction and his or her satisfaction in different areas of life. The positive correlation between life and sport satisfaction in a sports-oriented sample provided additional evidence of this association. This result was consistent with previous studies on the relation between life satisfaction and domains satisfaction. For people involved in sport more than three times a week and at a competitive level, satisfaction in this domain of activity seems to contribute to overall life satisfaction. Extraversion and neuroticism were significant predictors of life satisfaction (Diener et al., 2003). The personality dimensions related to sport satisfaction are linked to a lesser extent, although they were the same as for life satisfaction. Life satisfaction and sport satisfaction were correlated and predicted by the same personality dimensions in linear regression. Analyses at a facet-level showed that vulnerability, depression and positive emotions were the best predictors of life satisfaction as previously demonstrated by Shimmack et al. (2004). An interesting finding is that the configuration of the relations between personality and life and sport satisfaction were different. The facets of anxiety and positive emotions were significantly linked to higher levels of sport satisfaction. Success while participating in a sport is determined to produce a variety of positive feelings, and reduced the levels of excitement and anxiety (Wilson & Kerr, 1998). These results also showed that a more precise assessment of personality at the level of lean facets increased the variance that personality traits explain in satisfaction as indicated by Shimmack et al. (2004). Often, the facets predict additional variance that is lost by aggregating facets into global factors showing the necessity to study personality traits at different levels of specificity (Steel et al., 2008). Within the non- parametrical graphical regression analyses, we can precise the personality profile of a person with low and high scores on both satisfaction dimensions. This analysis can provide a more comprehensive insight into the relationships of personality with life and sport satisfaction. These graphics show that at high life satisfaction levels, neuroticism display low scores, whereas agreeableness and extraversion show high scores. This result is consistent with past research (Hills & Argyle, 2001; Steel et al., 2008) which found neuroticism (in negative) to be the predictor of happiness and life satisfaction and also with McCrae & Costa, Jr. (1991) suggestion that agreeableness would increase the probability of positive experiences in social and achievement situations. There are some notable differences in regard to sport satisfaction. A high sport satisfaction score was especially characterized by high levels of extraversion. The extravert feels more positive feelings in social situations than in not social situations (Pavot, Diener, & Fujita, 1990). The importance and frequency of socials contacts achieved by an extravert in sport situations could be one of the reasons that an extravert would have higher levels of sport satisfaction. According to Gray (1981) extraverts are also Personality in life and sport satisfaction 343 predisposed to be more satisfied in social situations such as practicing a collective sport, which is the case for the majority of our sample. A differential pattern concerning the conscientiousness dimension in regard to life and sport satisfaction was observed when comparing the graphical analyses. While conscientiousness showed a consistent association with higher scores in life satisfaction, this trend was weaker in the case of sport satisfaction. Persons with higher scores in sport satisfaction presented a profile with a high score in extraversion and a low score in neuroticism, while to a lesser extent they obtained higher scores in agreeableness and lower in conscientiousness. Besides, persons high in extraversion (participative, active, adventure seeker) and low in conscientiousness (inconformity, independent...) could present some sensation seeking personality traits, because in accordance with Zuckerman (1994), athletes tend to behave as sensation seekers. The openness to experience dimension was relatively stable across life and sport satisfaction, indicating its low influence in the prediction of both satisfaction dimensions. It should be interesting to link these results with the ones of the exercise dependence field. Hausenblast & Giaccobi (2004) showed that personality, and especially highs scores in extraversion and neuroticism, was linked to exercise dependence symptoms. Are those people with exercise dependant symptoms more likely to be satisfied or dissatisfied with their sport life? Is the link between life and sport satisfaction higher for those people? Are the peoples practicing sport more satisfied with their life than the ones noninvolved in this activity? Is being satisfied with his sport life could be an indicator of the sport adherence? Summing up, the present study shows that life and sport satisfaction were moderately related. The best personality predictors for life and sport satisfaction were extraversion and neuroticism even though their predictive value was higher for life satisfaction than for sport satisfaction. Using NEO-PI-R facets as independent variables, the accounted variance for life satisfaction improved but the change stayed very little (7% of the variance). Non-parametrical graphical analysis showed that the participants present a different personality profile in relation to life and sport satisfaction levels. References Aluja, A., Blanch, A, Solé, D, Dolcet, J.M., & Gallart, S. (2009). Validación de las versiones cortas del NEO-PI-R: el NEO-FFI frente al NEO-FFI-R. Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, 17, 335-350. Aluja, A., García, L. F., Cuevas, L., & García, O. (2007). Zuckerman’s personality model predicts MCMI-III personality disorders. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 13111321. Andrews, F. A., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being in America: the development and measurement of perceptual indicators. New York: Plenum Press. Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: perceptions, evaluations and satisfaction. New York: Sage. 344 Baudin, Aluja, Rolland and Blanch Cindy, H. P., & Koenraad J. L. (2005). Motivational orientations in youth sport participation: using achievement goal theory and reversal theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 605-618. Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R., & Rolland, J. P. (1998). Manuel de l’inventaire NEOPI-R. Paris: ECPA. DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: a meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197-229. Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. Diener, E., Emmons, R.A., Larsen, R.J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., y Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276-302. Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403-425. Dubin, R. (1956). Industrial workers’ worlds: the ‘central life interests’ of industrial workers. Journal of Social Issues, 3, 131-42. Duda, J. L., & Nicholls, J. G. (1992). Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and in sport. Journal of educational psychology, 84, 290-299. Fan, J., & Gijbels, I. (1996). Local polynomial modelling and its applications. London: Chapman and Hall. Fox, J. (2000). Non parametric simple regression: smoothing scatterplots. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A model for personality (pp. 246-276). New York: Springer-Verlag. Hausenblas, H. A., & Giacobbi, P. R. (2004). Relationship between exercise dependence symptoms and personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1265-1273. Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2001). Emotional stability as a major dimension of happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 1357-1364. Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five factor model of personality and job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 797-807. McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1991). Adding liebe und arbeit: the full five factor model and well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 227-232. O’Connor, B. P. (2005). Graphical analyses of personality disorders in five-factor model space. European Journal of Personality, 19, 287-305. Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164-172. Pavot, W., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1990). Extraversion and happiness. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 1299-1306. Rice, R. W., McFarlin, D. B., Hunt, R. G., & Near, J. P. (1985). Organizational work and the perceived quality of life: toward a conceptual model. Academy of Management Review, 10, 296-310. Roberts, G. C., Treasure, D. C., & Balague, G. (1998). Achievement goals in sport: the development and validation of the Perception of Success Questionnaire. Journal of Sports Sciences, 16, 337-347. Rode, J. C. (2004). Job satisfaction and life satisfaction revisited: a longitudinal test of an integrated model. Human Relations, 57, 1205-1230. Personality in life and sport satisfaction 345 Rojas, M. (2006). Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: is it a simple relationship? Journal of Happiness Studies, 7, 467-497. Schimmack, U., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality, 70, 345-384. Schimmack, U., Oishi, S., Furr, R. M., & Funder, D. C. (2004). Personality and life satisfaction: a facet level analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1062-1075. Steel, P., Schmidt, J., & Shultz, J. (2008). Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 138-161. Tait, M., Padgett, M. Y., & Baldwin, T. T. (1989). Job and life satisfaction: a re-examination of the strength of the relationship and gender effects as a function of the date of the study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 502-507. US Department of Health and Human Services (1996). Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease Control and Prevention, National center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Wilson, D. M., & Kerr, J. R. (1998). An exploration of Canadian social values relative to health care. American Journal of Health Behavior, 22, 120-129. Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University. Recibido: 14 de mayo de 2010 Aceptado: 28 de junio de 2010