PDF: Two "Marseillaise" Scenes: From Casablanca to West Beirut

CINE-FORUM

RICHARD RASKIN

TWO -MARSEILLAISE- SCENES:

FROM CASABLANCA TO WEST BEIRUT

Resume:

La scene

emouvante

de

la

« Marseillaise» execuMe avec

tant

de

brio dans

Casablanca est generalement interpretee comme celebration de Ia resistance et de

Ja liberte. Mais si on envisage cette scene du point de vue des maroccains qui s'op-

posaient

~

I'occupation coloniale--de leur pays, cette glorification fran-;aise de

Ia

111

Marseillaise

It devient un affront

a

la

liberte.

Dans cette perspective, une autre scene de la « Marseillaise. - celie de West

Beirut

de Ziad Ooueiri repond tt celie de

Casablanca

et en expose Ie discours refoule.

T he "Marseillaise" scene in Michael Curtiz's Casablanca (USA, 1943) has moved successive generations of moviegoers to tears since 1943. Even Mur-

as

he scripted the ray Burnett. the man who first conceived of the scene, wept duel of national songs: "I cried when I wrote it.

I literally cried when I wrote ir.

Tears, actuallears. I was writing and I cried. lIt was that powerful to me. And it was that powerfuJ in the film.'"

The following r~um~ may help to refresh the reader's memory as to exactly what happens in this scene, set in Rick's caf~:

Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Victor Laszlo (paul Henreid) are upstairs in Rick's office, with Laszlo offering t'O buy the letters of transit Ugarte (Peter Lorre) had. stolen from a courier.

Rick refuses. and in reply to Laszlo's question as to why, Rick tells him to ask his wile. They then hear German orncen; singing Die Wachl am Rhein in the main room below.

Rick and Laszlo go out on the balcony and look down at Major Strasser (Conrad Veidt) and his lellow officers singing loudly at the piano. Captain Renault (Claude Rains) watches [rom the bar, his eyebrow raised. turning to see what Rick and

Laszlo will do. Laszlo, listening tight-llpped, walks decisively down the steps and approaches the band, telling them: "Play the 'Marseillaise'!

Play it!" The band members look down, then up toward Rick who nods to them.

The band then begins to play the "Marseillaise," and lor a while, both the

German and French songs can be heard, as a kind of auditory duel. But follOWing Victor Laszlo's lead, virtually all the cafe patrons stand up from

CANADIAN JOURNAL 0' FILM STUDIES

0 nYUE CAHAD'lNHE D'trUDE.S ONUIAJoCRAPHlqUlS

VOLUME 15 NO.l° M.LL' AUTOMNE 1I1l'

0

,.11],-"8 their seats to join in the singing of the "Marseillaise." including many men in French uniforms, as well as the guitar-pla>;ng Spanish chanteuse (Corinna

Mura); even Yvonne (Madeleine leBeau), recently dropped by Rick and who had arrived that evening on the arm of a German officer, now sings the French national anthem with tears running down ber cheeks. Major

Strasser and his compatriots have long since given up their singing. Usa

Lund (Ingrid Bergman) quietly observes this symbolic triumph over oppression, with love and admiration in her eyes for the husband who had taken charge 01 the situation and known exactly what to do. When the last ven;e of the "Marseillaise" has been sung, people shout "Vive la France! Vive 1a

Democratiel" and Victor is cheered. and toasted by the French officers standing nearby, aiter which Major Strasser angrily "suggests" to Captain

Renault that Rick's

cafe

be closed immediately.

In earlier studies. I tried to show how this scene helped to shape the attitudes 01 U.S. audiences toward the Free (or Fighting) French,' and to look closely at the role of Bogart's nod in the scene.

3 In the present study. it is in relation to French colonialism that I want to focus on this scene and on the film more generally. And I would like to suggest that Ziad Doueiri's "Marseillaise" scene in

West Beirut (France/Norway/Lebanon/Belgium, 1998) might be considered a reply to its counterpart in casablanca.

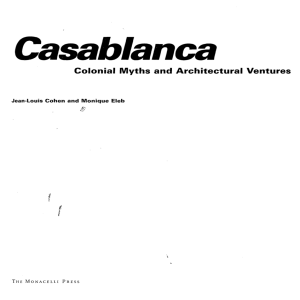

CASABLANCA AND COLONlAU5M

In describing her own experience of the .. Marseillaise" scene in casablan.ca,

Judith Mahoney Pasternak wrote, "'The 'Marseillaise' comes to its stirring conclusion, and with tears in their eyes the patriots in the bar cry out, 'Vive la France!'

Watching, lears in my own eyes, I always murmur along, 'Vive la France: It took

40 years for me to notice that they're shouting 'Vive la France!'

on

African

soil.

'"4

This imponant point has been missed by many commentators over the years.

As has been shown elsewhere (see endnote 2). much of the storytelling in casablam:a is designed to elevate the Resistance and the Free (or Fighting)

French in the eyes of the viewer, at a time when u.s. policy was utterly WlaCcommodating toward representatives of these organizations. And as numerous commentators have pointed out, the film casts in a positive light the transition from .neutrality 10 engagement. But while serving those laudable purposes. the storytelling in Casablanca also represses the reality that "French Morocco" as a colonialist construct involved for an indigenous people: a) subjection to French rule and exploitation; b) the frustration of their own sense of nationhood; and c) the overshadowing of their own Arabian-Berber culture by another.

The Jilm defines the city 01 Casablanca as "FIeDch soil" in an unequivocally positive way, meaning that as such, it is-at least in principle-free from Gennan author.

ity. Victor laszlo, the most politically admirable character in the fIlm, does this when

TWO '"'MARSEJLLAISr SCENES 113>

confronted by Major Strasser first at Rick's. To Strasser's assertion, "You are a subjecl 01 the German Reichl" Laszlo replies, "I've never a<:repled thaI privilege. and I'm here now on French soil.· And then again at the Prefect's office Laszlo insists. ·You won't dare to interfere with me here. 1bi.s is still Unoccupied France."

What a curious casablanca we have in this film, in which not a word of Arabic is heard, though we are treated to smatterings of Italian, French, Spanish,

German and even a bit of Russian. And there is only one character with an Arabic name in this film: Abdul, the doorman at Rick's.

Is it unfair to expect a greater recognition of the colonial realities in a film made in 19421 Nol il one considers the lollowing lacts. As early as 1924-1925, the Berber leader Abd al

4

Karim Al-Khartabi led "a resistance movement against

French and Spanish colonial rule in North Africa," and curiously. the Spanish and French forces fighting againsl him were commanded by none other than

Francisco Franco and Marshal Henri Philippe Petain, respectively.

5

On August 14,

1941, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston 'Churchill issued the Atlantic Charter.

the third provislon 0.1

which commits the signatories to "respect the right 0.1

all peoples to choose the form of government under which they wish to see sovereign rights will live; and they and self government restored. to those who have been forcibly deprived of them." 6 This provision would soon be cited by groups calling for Moroccan independence from French rule. such as the Istiqlal (fndepend.ence) Parry, officially established in 1944.

Furthermore, Roosevelt expressed his own views on the necessity for

Moroccan independence al the Casablanca Conference held in January 1943, when-al about the time of CasablanaJ's general release-the following meeting took place:

On the evening of January 22, the president [Roosevelt] invited Churchill and Morocco's Sultan Sidi Muhammad to dinner.... In deference to the sul· tan'S Islamic faith, Roosevelt served no alcohol, much to Churchill's chagrin.

The prime minister's dismay increased when Roosevelt steered the conversation toward colonialism, a particular sore point between the president and

Churchill, who wanted to maintain Britain's colonies after the war. Morocco had been a French protectorate since 1912, and Roosevelt sketched out for the sultan the role that America could play in post

4 colonial Morocco.

ChurchiU knew that Roosevelt'S views on France's colowes applied to

Britain's as weU, and the prime minister moved uneasily the conversation changed to another subject.

7 in his chair until

Those who might argue that the wartime situation made it inappropriate even to consider the issue of colonialism in North Africa, would be at odds with the views held by Roosevelt himself at the time Casablanca was first shown in movie theaters across the United States.

114 RlOtAaD lASKI N

Before returning to the "Marseillaise'" scenes in the two fIlms, I would like to cite one of Conor Cruise O'Brien's comments on Albert Camus's allegorical novel,

The

Plague (1947). The action in this novel takes place in the Algerian ciry of Oran, where a plague sets in and is fought, against all odds, by teams of medical workers. 1b some degree at least, the characters who fight against the plague-the dOClor Rieux and other

key

figures in the

"equipes sanilaires"

such as Tarrou and Grand-symbolize French Resistance groups in their snuggle against the Nazis. O'Brien incisively wrote:

The difficulty derives 1 believe from the whole nalUre of Camus', relation to the German occupiers on the one hand and to the Arabs of Algeria on the other.

It com~ natural to him, from his early background and education, to think of Oran as a French town and of its relation to the plague as that of a

French town to the Occupation. But just \>clow the surface of his consciOU5+ ness, as with aU other Europeans in Africa, there must have lurked the pos· sibility of another way of looking at things-an extremely distasteful one.

There were Arabs for whom 'French Algeria' was a fiction quite as repugnant as Hitler's new European order was for Camus and his friends. For such

Arabs, the French were in Algeria in vinue of the same right by which the

Germans were in France: the right of conquest. The fact that the conquest had lasted considerably longer in Algeria than it was to last in France changed. nolhing in the essential resemblance of the relations between CODquemr and conquered. From this point of view, Rieux, Tarrou and G.rand

were nOI devoled fighters against the plague: they were the plague itself.'

The same point could be made regarding casablanca: that from the perspective of those Moroccans who wished to see an end to the colonial occupation of their country, the glorification of France in the singing of the "Marseillaise" ntight be viewed more as an affront to freedom than as a true expression of it. In this respect, the "Marseillaise" scene in casa.blanca.

is an unfinished situation since it leaves unexpressed and unacknowledged an important aspE'~ct of the realities in play. Those very realities, kept from surfacing in Casablanca, are given full expression in a corresponding scene in Ziad Doueiri's Wesr Beirul.

THE MMARSEIUAlSE'" SCENE IN WEST BEIRUT

As this film begins. the setting is the schoolyard of a French Iycee in Beirut on

April 13. 1975, and aiter an initial scene in which the pupils observe a dogfight of two military jets in the sky overhead, resulting in the explosion of one of the planes. the children are called to order and told 10 line up for assembly.

The headmistress, Mme Vieillard, walks toward the flagpole. Tarek, a fifleeoyear

4

0ld boy, observes her, then suddenly puu; his books on top of his friend

Omar's and rushes 0(( without telling him where he is going. Mme Vieillard

TWO "M"ISEILLAlSl~ SCENES 115

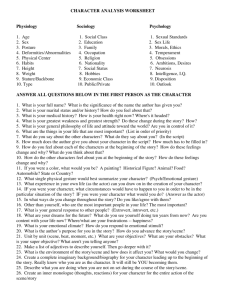

f"tgU,e: l. Mme vieillard the ~MatWillaisoe.·

Jeids the singirts fA F"CUrf' 2.

Ta,e«. on the bakony

Lebanew national anthem.

sines

the

..

'

~-.._~~

-

,

- "

~

}, ..

" . ' j - - -

< , come

,

,.\,

-

•

, r

.~

.

~

F'rgure 4.

Mme. YietJlard orders TarN to down from the bakony.

,

, rtgUre 1 TM8-'S.

schoolmates hom below.

watdtinJ

him arn\'eS.1t the- flagpole and begins 10 lead In the .singmg

of the "Marseillaise," Tarek ascends a StaUCd5e mside the school building..

enters a room. and emerges from

It again J.

moment la1.er cdrrying a megaphone. He lhen walks quickly along

a.

b.ll· cony. smiling. In the' courtyard below, the children cootlnue singing the "~1M seiUaise." TMek.

now s-hmdmg on a balcony overlooking t'he school>·ard. raises the- megaphone' 1.0 his mouth and begins to sing the LelMnesc n.llion~\1 anthem.

80th songs can now b. heard, Children who had been {acing Mille Vieillard and

SlOgmg the '"Marseillaise- now tum 10 face "rcIrek.

The-re J5 a moment or confusion as t-.1.me VieJJlo1rd tnes to understand whal is happerung. The other chlldren now jom m Tarek's singing of the Lebanese natIonaJ anihem. Mme ViellLird calls out to Tarek and orden him

(0

"come down from there'" (Figures 1-4). Ignoring her prolests.

Threk and his schoolmates finish their singmg and Tan~k waves the

VlClory sign to hi' enthralled and cheenng claS1l1la'es below, Omar can barely contain his admirauon for Threk.

A the cheering conlinues. Mme VfeiUard makes her way through the crowd. heading for an entrance (0 lhe budding.

In Ihe scene thai follows and that lakes place insidr the classroom. Tarek has been called up '0 'he bl.,'kbo.rd

to answer lor his rebellious beha\'lor. but responds 10 Mmt> VieiUard's ordel'3 and questions in a way lhat indirt."Ctly mocks her and the French cuhure she represents.

He is reprimanded and 1.hrown oul 01 the c1.usroom_ While Th.rek stands in the corridor and looks through a window,

:1me Vieillard sa LO the boy's da"mates (in FrE'nch). "We must not forget that

I I' ItCIIUO tARtM

France CTedted your counuy. France gave you fOur bon:Jel"5. We laughl you peace.

We prepared your ci"J1iz.atlon and your constitutlon. Know that educalion. French educauon in paniculJI. is me only means [or freeing you (rom your pnmltive custom ...... \VhHe loolting down at the street. Tarek notLCe5 masked gunmen laki,ng up positions along the side-.valk..

waiting m ambush fOf.1

bus Cdf-

rying Palesunians on \yham

they

will

soon

opt?n fire-an t"Vem mJ..rkmg the Slart

of Iht" civil war thai was to devastate LebJnon for the next fifteen years.

ZIAD DOUElRI'S OWN COMMENTS ON THE SCENE lToiepbone Interview. 14 AuCWt 2D04)

RR; West

Betruc

has been described as ninety per cent JUtOblographlcal, Doe!; that apply

(0 the "Marseillaise" s('en~l Did )-'Ou actually do what Tarek does in

IhLS scene?

ZD: No.

actually it's probably the most fiClion..ll scene 10 the film_ Because {in french [ydel we were never asked to do tha(. The school fiii."Ver performed me w!O

slOging pcnod.

The rea on \\'(' did it was tx:-cause for me. dr.lffi.1U(.'ally It worked.

For several reasons. wbich I'll explain in a moment And a.lso becaust:' Irs symbolic.

It s-hows molt the Lebanese studems al thal time, In thIS pdJUCUldI :;(hooL had .heir own iden'i'y which they wao'ed to display in 'foot of French authonry,

So It w,)s d way to say th.at

\\Ie are ready to rebel dgamSt you.

But ffid.inly the

b.lsK'allr.

reason 1 did that scent'__ ._ You knO\\.

In fe-dime fHms in dram.a. you can say whatever you want You're not bound by any responslblbty e.'(cept 10 make a llIrn that works. I wanted to sho\\' lh.1t

the m.110

cha.racter.

Tdre.k. is a rebel. He does not like authority, period. whatever illS.

And I thought thaI tbat SCene was .1

good manipulative way iOT me to ,],hieve that

No\-\'. I got ., 101 of hassle for lholt scene when the- film

WJS shown hi5l..~.

There Jre a 101 of pro-French people, people who 'hink \'ery highly of tile French and who are francophone, who Ir.wel to France for all of their vaCdtlO!1S.

~i.lin· ly the bourgeoisie. They really protested.

They said; "How can you do thaI?

\\'e never dJd thai!" They look 11 literally.

They could not 5epdralt' realily from fico tJon. And I kept on saYIng: "Well you know. Hus i jUSI.1

fictional thlllS" T1ev were pretty upset. Also some of the French dJplomals who were JOVlled from the embdssy were more civtltzed and diplomatic about n. but they aId: "You knilW.

we n{"\'er laught

you

thiS."

The currenl principal of the Lycee franCJjs-the sce-ne where thJS is supposed

(0 happen-he was not the pnndpaJ when I was

<1 teenag· er-he dlso said "I don'l think lhat's pan of our dgenda.ll our schoot., 10 teach any form of nationalism or patriolism," I hJd to explain to him ag3J.O that thiS was JUSt an idea, lO dramatically help the scene and help thiS character. whose rebelliousness. I wanted to show. J saId that if it had been an American setting in

Lebanon. J would have had him sing againsl the Amenc-an nalion.ll anthem.

So Ihal's basically what it was.

BUI

I still gal a 101 of shit for II (l.au,ghIl"~).

RR There

IS an obvIOUS companson 10 be made With the ".\1arsetJl.use'" scene fWD -M,uSlEILLAJU'" SCl!Nts

111"

in casablanca.

Old Ih.:n play any role at all for you, in imagining your own" Mar· seillaise'" seene-?

ZD: No. Not at

all.

COHCWSION

Though not Intended as such. the "MarseiJlaise" scene in \I\'est Berrut-involving a.!I

II does .l

duel 01 nauon.ll 301hems-can be underslood as a .fitling reply to the corresponchng scene in Casablanca. fin~Jly drawing into open view an implicit colonial element m that scene that gmer.uions of Western moviegoers and com· mentators hav~ missed. presutrulbly

as

a r..ulr of a cultural blind spot ...hieb

evl"l1 today is dtf(icuJt to recognize. The Casablanca scene will always remain a cinematic masterpiece. and will continue 10 Ihrill audiences around the world.

But It is ~1.lso

a record of an outlook that focuses on one occupation while repress-ing all awareness or acknowledgment of another.

NartS

).

Interviewed in You Must Remembet This: A Tribute to ·Cosoblanca: a vtdeo produced

.n<!

dire<tod by Scott 8enson (1992).

The ........

-to-~roduced >toge play "Eft1Ybody

Comes 10 Rick's,· by Mumrt Burnett and JOtO Alison. was the initial basis

'Of the

Coscbkmco scr~pl'Y.

1.

~d Raskin.

·CtJSOb/onco and US. Foreicn Poicy," first pubtished in Raskin.

The func.-

_ ~ 0# Art: An ApproocJJ !o

11M!

SoOOI ond Psyd>oIogicoJ F1Jnctiom 01 Uteroture, Pointing ond Film (Aarhus:

Film Histoty4 (1990): lSJ-l64.

Atlon., 1982), 2n-315; reprinted in abridgoed form in

4.

3.

Richard Raskin.

"'Bog~rt's Nod in the Morseilloise ~I!: A PhysiQl Gesture in C'..osob/otJ.

co,· in p.o,tl.: A Dantsh Journal 01 Film Sttxhes 14 (December 20(2): 136-142. AlIJitable

"htlp://po"",,•.

au.dIV1ssu'U4/Se<lio'U/art£1SA.htmI

(occessed 31 July 2007).

)udil!l . . .

ho.....

Pasternak, 'The Shilling Sond$ 01 Riglltl!OUSO<SS.

C.."b!o..

,o

(1942)'-

Non>dolenl AdJ~ The Mogozil>e 01 rho War R....rets LOCJ9I'f' (May-June 2000).

htlp://wwN.wlrre:sisten.Ol'glnva0500-8.htm

(~ J 1 July 20(1).

S.

See I..

ewnple

July 20(7).

lntp;f/enqtlopedia.thelreedi<tional'/.(om/_Krim (aa:essed 31

6.

lntp://www.y.Ie.<du/1awweb/...lon/wwilatlantidl1m (acces.sed

31 July 20(1).

7.

Raymond ter

w.

Copson, -p,esident ffanlUin D. Rl,)()SeYt'lt Flew to Meet British Prime Minis.-

Winston Chu,dUll fOf a Summit.

in Casablanca.

W av_labfe at: htlp:/ /www..histo<ynet.CD<TI!QlIturefloreign_affo

i..no33881.htmI1showAll-y&o-y

(accessed 31 July 2007).

&.

Conor Cruise: O'~, Comus (london: FontJ~ 1970), 47·4& A di5.cusSlOn

of the poIitic.aI

meanings af rhe Plague can be found ;n Raslcin.

The Functioncl Analysis 01 Art, 255-276.

RICHARD RASKIN te.lChes

screenwriting and video production at Aarhus Univecsily tn

Denmark,

wheel> he also e<lns p.o.1I. , A DanISh Joumal of Film Sludie:;.

His books include ~ Funcllonal AnalysIS of Art: An Approach co rIlE Social and PsycIrD/ogzaJl FrmcriDn of

Lu_.

Pamring and FUm (1982), Alain /lesnai$'s Nuil d

BrouiUiJrd: On rIlE Malang. I1fo?plion and FlUlCtwlU af a Major Docuntenuuy Fibn

{l9B7].

~ AlroftheSlwrt FiawnFflm' A Slwr-by-Shor Srudyof Nine Modem C1f.usia (2002), and A auJd III GW'poinl: A Case Study in IIlE Ufe of a Phoro (2004).

111 atQMItD RAIKIN

REVIEW-ESSAY • ESSAI COMPTE RENDU

BART TESTA

THE CINEMA Of ATTRACTIONS RELOADED l d _ by Wando Slrawen

Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 2006,460 pp

IS

Tale enough for a critical slogan to gain the Wlde currency th,u Tom Gunt I ning's .. the dnerna of 3UfaetJons" has. but what is there to diSCUSS funher

'l'1w about the idea, which Cunning has expiained variousiy but al....

ys clearly?

Cinem.a of AttTnalOflS Reloaded. or a third of n, seeks 10 answer that Quesuon

AnOlher thud 15 a ktnd of inlellectual

archeology.

The remainder is speculah....e

dilal.ion and re-tasklOg of thl? concept.

In 1982. four ye.lrs before the "attractions" coinag.e. Cunmng tOok his first

SWIpe at the ,dea WIth -The Non·Continuous Style of Early Fdm. 1900-1906" and pursued 11 in -An Unseen Energy Swallows Space. Tbt" Space in Early FUm .1nd

lts ReIJtion

(0

American AVJm·Carde Film" (l9S3). Fmall}' puttmg the phrJse inlo play with "The Cinema nf Attraction: Early Cinema.

Its SP<'C,ator. and the

A.ant·Garde" (1986), Gunning

sa...

it anthologIUd and gJioing liS plural "AUlactioos" in 1990 in Thomas Elsaes er's Important anthology Earl}' Cmema. Spa£l" frome Narratwe.

l

TIle back-story chronology is developed further in editor Wanda SUduven's wonderiully wacky flow chan. embedded in her earnest introducuon to Cmema of A/l'I'OCCioIU Reloaded. Her~ in brief: "The Cinema 01 Auracllo,,- (smgul"'l beg.n a a confeIence paper In 1985, close by Andre Gaudreault's "Le cinero.

des premier lemps: un dtHi a "histeire de cinema?M

GdudreJuJfs lecture was published.

10

Japanese, in the lbkyo Journal Gertdm ShlSo. Just before thJS.

Don· ald Grditon used the term ·dttraction"' in a talk on slapstick comedy at MOMA

(Gunning was present). Ho...ever. Grafton published

his

talk !a'e enough (in

19B7) to be quoting Gunning's 1986 essay as if it preceded his o...n

use

of the lerm.

There

were

more "attractions· essays to come. with surpnslOgly few redundancies, up to as recently as 2005 when Gunning published WCmema of Attractions" in RIchard Abel's EncyclopedUl of Earfy CinertUl.' The dUfft Impad of these texis is probabJy less remarkable than tbe ca~{ Of the phrase "cinema at attractions" llself. which persuadE'S oDe IM1the explanatory aspects or a volume, even one as unwieldy as The C,nema of Attraaiolt$ Reloaded.

and as peculiarly

CA.HJUJIAN JOURNAl. OF JlLM STUDIIS' IIVUE CANADII.NNI D'truDIS CIHtaulToGkAPtHQUlS

VOLUME I ' NO.1· 'ALL' "UTOMNE no,· pp 11t~ln