SYNTHESIS OF RESEARCH

ON SELF-CONCEPT

T

heories about self-understand

ing have ranged from romantic,

holistic ideas expressed through

the fine arts, to highly analytic state

ments emerging from psychological

research on specific aspects of per

sonality. Theorists disagree about

whether the environment or the indi

vidual is more influential in their

formulation. At present comprehen

sive statements about the self must

remain somewhat speculative, but an

examination of theory and research

does offer some important informa

tion about how people perceive

themselves C James, 1890; Mead,

1934; Rogers, 1962; Jourard, 1971;

Hamacheck, 1965; Gergen, 1971;

Rosenberg. 1979).

Self-perception seems to function

at three levels: specific situation,

categorical, and general. First, in our

daily lives each of us is involved in,

many specific situations in which we

exercise and develop ideas about our

knowledge, skills, beliefs, attitudes,

and the like. Second, as a function of

experience and desire, each of us has

perceptions about ourselves based on

various roles we play (learner, family

member; and attributes which we be

lieve we possess. Third, each of us

seems to have a genera! sense of self,

perhaps based on decisions about our

situation experiences and categorical

perceptions.

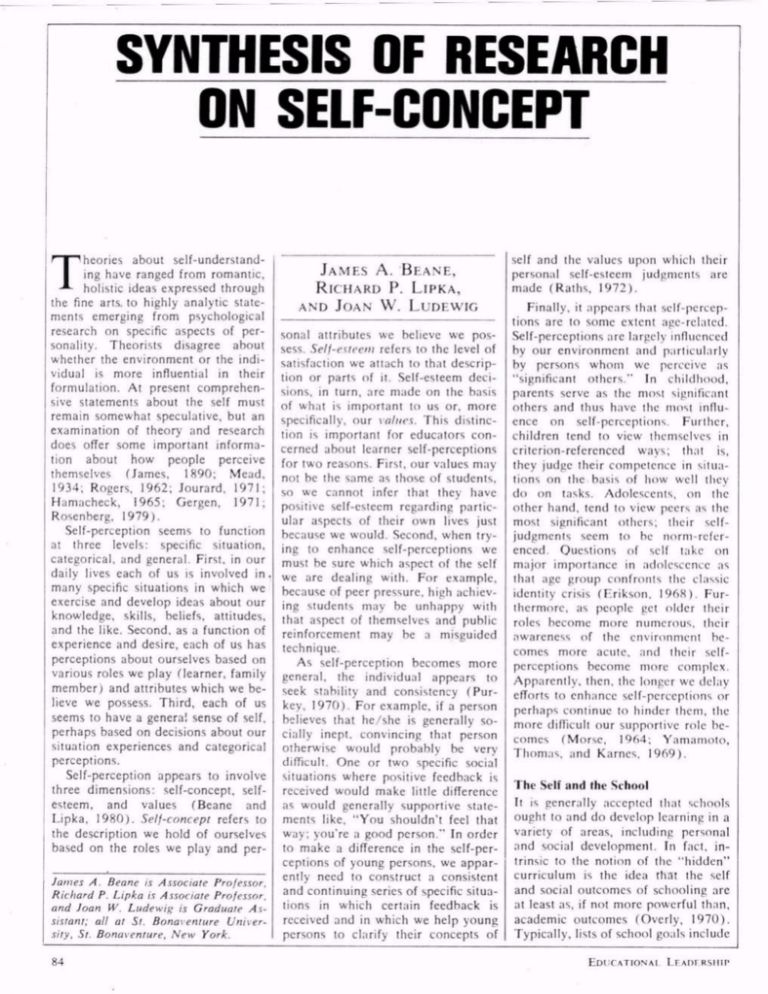

Self-perception appears to involve

three dimensions: self-concept, selfesteem, and values (Beane and

Lipka, 1980). Self-concept refers to

the description we hold of ourselves

based on the roles we play and perJatnes A. Beane is Associate Professor,

Richard P. Lipka is Associate Professor,

and Joan W. Ludewig is Graduate As

sistant: a/I at St. Bonaventure Univer

sity, St. Bonaventure, New York.

84

JAMES A. BEANE,

RICHARD P. LIPKA,

AND JOAN W. LUDEWIG

sonal attributes we believe we pos

sess. Self-esteem refers to the level of

satisfaction we attach to that descrip

tion or parts of it. Self-esteem deci

sions, in turn, are made on the basis

of what is important to us or, more

specifically, our value';. This distinc

tion is important for educators con

cerned about learner self-perceptions

for two reasons. First, our values may

not be the same as those of students,

so we cannot infer that they have

positive self-esteem regarding partic

ular aspects of their own lives just

because we would. Second, when try

ing to enhance self-perceptions we

must be sure which aspect of the self

we are dealing with. For example,

because of peer pressure, high achiev

ing students may be unhappy with

that aspect of themselves and public

reinforcement may be a misguided

technique.

As self-perception becomes more

general, the individual appears to

seek stability and consistency (Purkey, 1970). For example, if a person

believes that he/she is generally so

cially inept, convincing that person

otherwise would probably be very

difficult. One or two specific social

situations where positive feedback is

received would make little difference

as would generally supportive state

ments like, "You shouldn't feel that

way; you're a good person." In order

to make a difference in the self-per

ceptions of young persons, we appar

ently need to construct a consistent

and continuing series of specific situa

tions in which certain feedback is

received and in which we help young

persons to clarify their concepts of

self and the values upon which their

personal self-esteem judgments are

made (Raths, 1972).

Finally, it appears that self-percep

tions are to some extent age-related.

Self-perceptions are largely influenced

by our environment and particularly

by persons whom we perceive as

"significant others." In childhood,

parents serve as the most significant

others and thus have the most influ

ence on self-perceptions. Further,

children tend to view themselves in

criterion-referenced ways; that is,

they judge their competence in situa

tions on the basis of how well they

do on tasks. Adolescents, on the

other hand, tend to view peers as the

most significant others; their selfjudgments seem to be norm-refer

enced. Questions of self take on

major importance in adolescence as

that age group confronts the classic

identity crisis (Erikson, 1968). Fur

thermore, as people get older their

roles become more numerous, their

awareness of the environment be

comes more acute, and their selfperceptions become more complex.

Apparently, then, the longer we delay

efforts to enhance self-perceptions or

perhaps continue to hinder them, the

more difficult our supportive role be

comes (Morse, 1964; Yamamoto,

Thomas, and Karncs, 1969).

The Self and Ihe School

It is generally accepted that schools

ought to and do develop learning in a

variety of areas, including personal

and social development. In fact, in

trinsic to the notion of the "hidden"

curriculum is the idea that the self

and social outcomes of schooling are

at least as, if not more powerful than,

academic outcomes (Overly, 1970).

Typically, lists of school goals include

EDUCATIONAL LF.Anr-.RSiup

statements of intent to help students

develop a positive sense of self-worth,

in

self-confidence

independence.

learning, and internal locus of control

(that is, self rather than external

direction).

In the hundreds of studies that

have been done, a persistent relation

ship has been found between various

aspects of self-perception and a wide

variety of school-related variables

(Wylie. 1979). Among the variables

which have been found to be related

to self-concept are school achieve

ment, perceived social status among

peers, participation in class discus

sions, completion of school, percep

tions of peers and teachers of the

individual, pro-social behavior, and

self-direction in learning.

Students carry images of the self in

several areas as well as the potential

for developing many more. These

might include the self as person, as

learner, as academic achiever, as

peer, and others. Each experience in

school can affect self-concept, per

sonally held values, and/or the sub

sequent self-esteem of the learner.

For this reason, an understanding of

self-concept and esteem in general,

how they function in youth, and how

the schools might enhance or hinder

them must be a major concern of

those responsible for curriculum

planning and implementation.

Using the broad definition of cur

riculum as all of the experiences of

the learner (both in and out of class)

under the auspices of the school, we

may now turn to an examination of

the interaction between the self and

the institutional features of the

school.

From Custodial Climate to Human

istic Climate. D iscussions of school

climate generally distinguish between

two types, custodial and humanistic.

Dcibert and Hoy (1977) found that

students in humanistic schools

demonstrated higher degrees of selfactualization than those in schools

with a custodial orientation. This cor

relational research has obvious im

plications for schools when one

examines the qualities associated

with each type of climate. The cus

todial climate is characterized by con

cern for maintenance of order, prefer

ence for autocratic procedures,

student stereotyping, punitive sanc

tions, and impersonalness. The

humanistic climate is characterized

OrroBFR 1 980

by democratic procedures, student may vary from the group (Purkey,

participation in decision making, 1978). In other words, homogeneous

personalness, respect, fairness, self- grouping based on an attribute such

discipline, interaction, and flexibility. as ability may lead not only to aca

In other words, it appears that the demic disadvantage (Esposito. 1973).

but to labeling of students. In this

custodial climate may be a debilitat

ing factor in the concept of self while way the school may introduce to the

learner confusing self-descriptors and

the humanistic climate might be con

sidered facilitating (Licata and negative self-esteem suggestions. The

Wildes, 1980; Estep, Willower, and emphasis on ability is unfortunate

Licata, 1980).

considering the wide array of options

From Accepting Failure to Ex- available for grouping. Self-concept

peeling and Ensuring Success. In would probably be facilitated by use

some schools, it is expected that many of a variety of grouping patterns de

pending upon the task to be accom

learners will fail. Further, it is ex

plished.

pected that some will do so consis

From Age-isolation to Multi-age

tently. Thus failure has a kind of

cumulative effect for the learner Interactions. Schools isolate one age

(Purkey, 1970) and also becomes group from another and youth from

embedded in teacher expectations adults as well as from other youth.

(Rosenthal. 1970; Kash and Borich, Efforts need to be made to help

1978). Within this framework, one young people understand the age

may find interaction effects (Bloom. levels from which they have emerged,

1980; Purkey. 1970) between self- as well as those toward which they

concept as learner and school are headed. In the case of the former,

multi-age tutorial and discussion ses

achievement (for example, correla

sions with younger persons appear to

tions for academic achievement ap

be particularly useful in facilitating

pear to range up to .76).

The general id.ea that "one success the sense of self (Lippitt and Lippitt,

may lead to another" is supported 1968. 1970). With regard to later

experimentally by the work of Bailiffe life, clear and constructive views may

(1978) who suggests the use of be facilitated when students are en

teacher-guided tutoring sessions, in couraged to interact with adults of all

ages. One particularly interesting

which a successful outcome is en

sured, followed by discussion of how variation concerns interaction with

it feels to succeed. Another useful elderly people for the purpose of

technique is that of team learning, encouraging positive views of that

particularly in relation to cooperative group as well as life at that age (Tice,

reward structures (Slavin and De 1979). In this case, schools that in

volve elderly people in daily activities

Vries, 1979).

At a more general level, teachers within the schools and which provide

as significant others must consistently- opportunities for young people to do

community service projects for and

signal learners that they can success

fully pursue the academic, social. with this age group are probably en

hancing one dimension of self-percep

and personal goals of school experi

ence. It should be noted that self- tion, the self as potential adult.

concept and esteem appear to be

From Avoiding Parents to Work

necessary but not sufficient for ing With Parents. To enhance selfsuccess (Purkey. 1970), particularly perceptions, the school must make

if the task at hand is completely attempts to influence parent/child in

beyond the grasp of the learner. teraction since parents continue even

Thus, planned activities should not through adolescence as significant

be beyond the grasp of the learner if others. Three strategies seem promis

feared or actual failure is to be ing. Through parenting workshops,

avoided. In any event, self-concept parents may learn the interaction pat

and esteem as learner may account to terns necessary to develop self-con

a large degree for school success and cept and self-esteem (Brookover,

may be enhanced by teacher action. 1965; Bilby. 1973). A second stra

tegy is the use of conferences in

From A ttrihute Grouping to Vari

able Grouping. Teachers often label which, under the guidance of the

groups, and then attach to individuals teacher, the parent, teacher, and stu

the general characteristics of the dent discuss the learner's life in

group, even though the individual school and define ways in which all

85

three might work cooperatively

toward improvement. A third strategy

involves attempts to promote the

"teaching home" (Tacco and Bridges,

1971). Academic achievement and

thus self-concept as learner appear to

be enhanced when parents teach their

youngsters (Bloom, 1977; Hess and

Shipman, 1965, 1968). For example,

cooperative planning sessions or par

enting workshops can initiate in

stances of "homework" which call

for parents and learners to work to

gether to solve problems, find infor

mation, or discuss issues. These and

similar strategies have great potential

for overcoming home-school separa

tion.

Imposed

Institutionally

From

Rules to Cooperatively Made Rules.

One of the key issues in developing

a positive sense of self-worth is the

degree to which the individual per

ceives control over his/her life. As an

institution, schools typically have a

set of rules that govern student life.

Further, these regulations are tradi

tional and mostly non-negotiable.

This feature of custodial climate un

doubtedly contributes to a sense of

external rather than internal locus of

control (Lefcourt, 1976) as well as

the related possibility of learned help

lessness (Ames, 1978). In other

words, the school's impositions can

debilitate self-perception and must be

HIGHLIGHTS FROM RESEARCH

ON SELF-CONCEPT

Self-concept i s the way

Providing for inter

people describe themselves

action with younger and

based on the roles they

older people by arranging

play and the personal at

for cross-age tutoring and

tributes they think they

involving elderly people in

possess. Self-esteem i s the

school activities.

level of satisfaction they

Assisting parents to

RESEARCH

attach to those descrip

enhance their children's

INFORMATION

tions, based on their

self-perceptions by con

SERVICE

values.

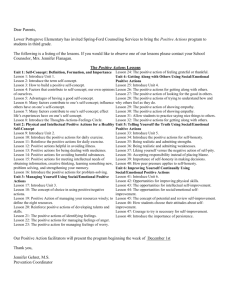

ducting workshops for

them, holding parent/student/teacher

Educators need to be aware that:

conferences, and encouraging parents

Students may not see themselves to take an active role in their chil

the way, others see them because dren's learning.

their values may be different.

Permitting students some control

General perceptions of self are over their own lives by having them

quite stable, so continuing, consistent, participate in formulating school rules

positive feedback will have more ef

and in teacher-student planning.

fect than a few random compliments.

Including curriculum that gives

It may be easier for adults to direct attention to personal and social

influence self-perceptions of younger development.

children than older ones because

Teaching students to evaluate

children are more apt to consider their own progress.

adults "significant others," while

adolescents are more concerned with

Reference

opinions of their peers.

A.; Lipka, Richard

James

Beane,

Schools can contribute to student

P.: and Ludewig, Joan W. "Interpret

self-esteem by:

ing the. Research on Self-Concept."

Creating a climate characterized Educational Leaders/tip 3 8 (October

by democratic procedures, student 1980): 84-89.

participation in decision making, perFor sources of information about

sonalness, respect, fairness, self-dis

topics of current interest to ASCD

cipline, interaction, and flexibility.

members, write to:

Minimizing failure and empha

sizing success experiences through Research Information Service

such practices as team learning.

Association for Supervision and

Using a variety of grouping pat

Curriculum Development

terns rather than always grouping stu

225 N. Washington St.

dents by ability.

Alexandria, VA 22314

revised to enhance a sense of selfcontrol.

This might be accomplished by the

use of town meeting-type activities or

committees on a classroom and/or

schoolwide basis. Teachers can use

teacher-student planning. Such ef

forts must, however, be open and

honest (Combs, 1962), not simply a

means to make students think they

have a decision-making role in the

school. In both learning and behav

ior, schools ought to provide con

tinually expanding opportunities for

self-responsibility (Delia-Dora and

Blanchard, 1979).

From Subject Approaches to LifeCentered Approaches. Educators

have Iqng recognized the lack of con

nection between the completely sub

ject-centered curriculum and the

personal needs of youth (Hopkins,

1941; Aiken, 1941; Alberty and Alberty, 1953; Krug, 1957; Hanna and

others, 1963). Proponents of the sub

ject-centered organization would cer

tainly support the idea that if one

wants students to learn subject mat

ter, the school must teach it. For

some reason, however, it is presumed

that personal and social development

do not need direct attention.

One way, then, of enhancing selfconcept and esteem in the school is

to provide a curriculum specifically

designed for that purpose. Through

such units as "Developing My Per

sonal Values," "Getting Along With

Others," "Living in Our School," or

other interest/need-centcrcd topics,

learners have the opportunity to ex

plore directly the personal issues and

environmental forces involved in

thinking about and making decisions

related to self-perceptions. Learning

would then move away from text

books and tests toward problems and

projects. The passive learner whose

school activities consist of studying

someone else's concerns, by their

method, is hardlv developing a per

sonal sense of self as learner. On the

other hand, studying personally im

portant problems and creating or con

structing related projects offers a tre

mendous opportunity to develop a

sense of self as an ongoing and cap

able learner.

From A dull-Exclusive Evaluation

to More Self-Evaluation I t has been

said that "in our society we grade

meat, eggs, and kids." In most cases

the kids have about as much say in

EDUCATIONAL I,rAi>rRsnn>

that procedure as do the others. A

clear and accurate self-concept de

pends upon the learned skill of selfevaluating (Barrett, 1968). Each

day, week, and so on. learners ought

to be encouraged to evaluate them

selves. Through the use of logs, jour

nals, and diaries young people may

keep a personal record of how they

do in various activities in and out of

school and look back at their devel

oping skills and growing insights in

all domains of learning and develop

ment. Further, each report on school

progress ought to have a written

statement by the student as to what

he/she has learned, what problems

have been encountered, how they

have been overcome, and what is

planned next. These procedures aim

directly at self-perceptions of learn

ers and their use is imperative for en

hancing the sense of self through the

school (Coons and McEachern,

1967; Marston and Smith, 1968).

Beyond the Status Quo

The correlational studies reviewed to

this point are interesting, perhaps

enlightening, possibly helpful, but

also probably suspect. By "suspect"

we do not moan to question the

competence of individual researchers;

the work is suspect because of grow

ing pains in the field. Until very re

cently two issues loomed large in the

field of self-perception research; the

imprecision of definitions in the field

and the related concern of inappro

priate instrumentation.

For almost 20 years, reviews have

noted that the imprecision and vari

ation in definitions and constraints

have hindered the interpretation and

generalizabilily of self-perception re

search (Wylie, 1961; Shavelson and

others, 1976; McGuire and others,

1979; Beane and Lipka. 1980). Most

noteworthy was the lack of distinc

tion between self-description and

self-evaluation, a condition which

has led to the interchangeable use of

the te.rms self-concept and selfesteem. As noted earlier, while these

terms are conceptually related within

the framework of self-perceptions,

they are distinctly different dimen

sions. The problem which arises if

they are not differentiated is illus

trated with an example from Coopersmith's Sell-Esteem Inventory ( 1967).

When a child says, "I would rather

play with children younger than me,"

OCTOBPR 1980

the response is interpreted as indic

self is tied to academic performance

ative of negative self-esteem since and the quality of the relationships

conventional thinking suggests that he she has with fellow students and

such a child feels rejected by age- teachers.

mates. While this may be the case

Our recent research (Lipka. Beane.

with the child who is consistently and Ludewig. 1980) employed the

rejected by age-mates, what of the spontaneous self-concept method but

oldest child in a several-sibling, added the dimensions of self-esteem

closely-knit family who feels positive and value indicators by asking stu

playing with younger siblings, or the dents whether they wanted to keep

child who has equal success with or change each item in their self-con

children of the same age and with cept description and why they would

older children, so does not regard age want to keep or change items refer

as important? Research that infers ring to school (at no time were

self-esteem from self-concept data prompting questions like "tell me

must be considered questionable.

about yourself in school" or "how

A second issue is that the field has about friends" asked). In interviews

historically relied on instrumentation with 1.102 kindergarten through

which is of a reactive nature (Cooper- twelfth-grade students the subjects

smith. 1967; Fills, 1964; Piers and generated a total of 8.955 self-con

Harris. 1964). Such instruments re

cept mentions of which 1.524 or 17

quire individuals to indicate how they percent were related to school. As

feel about themselves with regard to was the case with McGuire's work,

various attributes or situations im

age trends were noted with .58 school

posed by the instrument. However, mentions per kindergarten student as

this methodology leaves two ques

compared to 2.31 per twelfth grader.

tions unanswered. First, apart from

The analysis of school mentions

the research setting, do the respond

in terms of self-concept content, selfents even think of themselves in concept qualifiers, self-esteem, and

terms of the attributes or situations value indicators has revealed some in

presented? Second, which dimensions teresting and useful results. First, it

do they think in terms of?

is safe to say that about a fifth of a

To date one of the clearest at

child's sense of self is derived from

tempts to resolve these issues can be the school experience and that "self

found in McGuire's (1976. 1978. within the institution" and "self as

1979) work on spontaneous self- engaged learner" are the most salient

concept of children. By asking chil

categories within that experience. As

dren a question like "tell me about students move upward through the

yourself." the child is allowed to gen

institution, thev describe themselves

erate his her own list of self-concept within the institution in increasingly

descriptors based on personal sali

harsh terms. Finally, elementary and

ence. In McGuire's (1979) research secondary students have different

which involved use of the spon

value bases for their self-esteem.

taneous technique in interviews with Elementary students value positive

560 children from grades one. three, instructional activities, with an eye to

learning as fun. under the guidance

seven, and eleven school topics oc

of teachers with positive personality

cupied 1 1 percent of their self-con

cept content. This placed the school characteristics. Secondary students

fifth, behind, family (17 percent), value a concern for life plans within

recreation (14 percent), daily life a structure that encourages positive

and demography (13 percent), and interactions with peers.

The work reviewed herein demon

friends and social relations (11 +

percent). There were clear age trends strates that school looms large in the

in the data, with mentions of school self-perceptions of children and

constituting about 5 percent of first youth. It follows that schools have the

graders' self-concepts compared to opportunity and responsibility to en15 percent of those of eleventh grad 'hance the development of individuals

ers. In fact, by the eleventh grade beyond the acquisition of facts.

school is the largest single category

References

while the family was mentioned less

Aiken, Wilford. The Story of ilie

than 5 percent of the time. Analyzing Eight Year Sniiiy. New York: Harper

the mentions of school led McGuire and Brothers. 1941.

to conclude that a student's sense of

Alberty, Harold, and Alberty. Elsie

87

J. "Designing Programs to Meet the

Common Needs of Youth." In A dapt

ing the Secondary School to the Needs

of Youth. .Edited by Nelson B. Henry.

Chicago: National Society for the Study

of Education. 1953.

Ames, Carol. "Children's Achieve

ment Attributions and Self-Reinforce

ment: Effects of Self Concept and Com

petitive Reward Structure." Journal of

Educational Psychology 69

(June

1978): 345-355.

Bailiffe, Bonnie. "The Significance of

the Self-Concept in the Knowledge So

ciety." Paper presented at the SelfConcept Symposium, Boston, 1978.

Barrett. Roger L. "Changes in Ac

curacy of Self-Estimates." Personnel

and Guidance Journal 4 7 ( 1968): 353357.

Beane, James A., and Lipka. Richard

P. ".Self Concept, Affect and Institu

tional

Realities."

Transescence

V

(1977): 21-29.

Beane. James A., and Lipka, Richard

P. "Self Concept and Self Esteem: A

Construct Differentiation." Child Study

Journal X (1980): 1.

Bilby, Robert W.; Vonk, John A.;

and Erickson, Edsel L. Parental Var

iables as Predictors of Student Self-Con

ceptions of Ability. Paper presented at

the Annual Meeting of the American

Educational Research Association, New

Orleans, February 1973.

Bloom, Benjamin S. "The New Di

rection in Educational Research: Alter

able Variables." Phi Delta Kappan 6 L

(February 1980): 382-385.

Bloom, Benjamin S. "Human Char

acteristics and School Learning." Paper

presented at the National Symposium

on Teaching and Learning, Chicago,

1977.

Brookover. Wilbur B. Self Concern of

Ability and School Achievement. /I:

Improving

Academic

Achievement

Through Student Self Concept En

hancement. East Lansing, Mich.: Office

of Research and Publications. 1965.

Combs, Arthur W. "A Perceptual

View of the Adequate Personality." In

Perceiving. Behaving. Becoming. Edited

by Arthur W. Combs. Washington.

D.C.: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development, 1962.

Coons. W. H.. and McEachern, D.

L. "Verbal Conditioning. Acceptance of

Self, and Acceptance of Others." Psy

chological Reports 20 (I 967) : 715-722.

Coopersmith, Stanley. The Anteced

ents of Self Esteem. San Francisco: W.

H. Freeman and Co., 1967.

Deibert. John P., and Hoy. Wayne

K. "Custodial High Schools and SelfActualization of Students." Education

Research Quarterly 2 ( Summer 1977):

24-3 I.

Delia-Dora, Delmo, and Blanchard.

Lois J., eds. Moving Toward Self-Di

rected Learning. Washington, D.C.: As

sociation for Supervision and Curricu

lum Development, 1979.

Erikson. Erik H. Identity: Youth and

Crisis. New York: W. W. Norton and

Co., 1968.

Esposito, Dominick. "Homogenous

and Heterogenous Ability Grouping:

Principal Findings and Implication for

Evaluating and Designing More Effec

tive Educational Environments." R e

view of Educational Research 4 2

(Spring 1973): 163-179.

Estep, Linda E; Willower, Donald

J.; and Licata, Joseph W. "Teacher

Pupil Control Ideology and Behavior as

Predictors of Classroom Robustness."

High School Journal 6 2 (January

1980): 155-159.

Fitts, Williams H. T ennessee Self

Concept Scale. N ashville: Counselor

Recordings and Tests. 1964.

Gergen, Kenneth J. The Concept oj

Self. N ew York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. Inc., 1971.

Hamacheck. Donald E., ed. The Self

in Growth, Teaching and Learning.

Englewood Cliffs. N.J.: Prentice-Hall,

Inc., 1965.

Hanna. Lavone A.; Potter. Gladys L.;

and Hagaman, Neva. Unit Teaching in

the Elementary School. New York:

Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Inc., 1963.

Hess. Robert D., and Shipman. Vir

ginia C. "Early Experiences and the

Socialization of Cognitive Modes in

Children." C hild Development 3 6

(1965): 869-886.

Hess. Robert D.. and Shipman, Vir

ginia C. "Material Influences Upon

Early Learning: The Cognitive Environ

ments of Urban Preschool Children." In

Early Education: Current Theory, Re

search and Action. Edited by R. D.

Hess and R. M. Bear. Chicago: Aldine

Press. 1968.

Hopkins. L. Thomas. Interaction:

The Democratic Process. N ew York:

D C. Heath Co.. 1941.

James, William. Principles of Psvchology. 2 vols. New York: Holt, 1890.

Jourard, Sydney M. The Transparent

Self. N ew York: D. Van Nostrand Co..

1971.

Kash. Marilynn M., and Borich, Gary

D. Teacher Behavior and Pupil SelfConicpi. R eading. Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1978.

Krug. Edward A. Curriculum Plan

ning. N ew York: Harper Brothers.

1957.

Lcfcourt, Herbert M. Locus of Con

trol: Current Trends in Theory and Re

search. N ew York: John Wiley and

Sons, 1976.

Licata. Joseph W., and Wildes, James

P. "Environmental Robustness and

Classroom Structure: Some Field Oper

ations." High School Journal 6 3 (Janu

ary 1980): 146-154.

Lipka, Richard P.; Beane. James A.;

and Ludewig, Joan W. Self Concept/

Esteem and the Curriculum. Paper pre

sented at the Annual Conference of the

Association for Supervision and Cur

riculum Development, Atlanta, Ga.,

1980.

Lippitt. Peggy, and Lippitt. Ronald.

"Cross-Age Helpers." Today's Educa

tion 5 7 (1968): 24-26.

Lippitt, Peggy, and Lippitt, Ronald.

"The Peer Culture as a Learning En

vironment." Childhood Education 4 7

(1970): 135-138.

Lounsbury. John H., and Vars, Gor

don E. A Curriculum For The Middle

.School Years. New York: Harper and

Row, 1978.

Marston, Albert R., and Smith, Fred

erick J. "Relationship Between Rein

forcement of Another Person and Self

Reinforcement." Psychological Reports

(1968): 22, 83-90.

Mead, George H. Mind. Self and So

ciety. C hicago: University of Chicago

Press, 1934.

McGuire, William J.; Fujioka. Terry;

and McGuire, Claire V. "The Place of

School in the Child's Self-Concept."

Impact on Instructional Improvement

15 (1979): 3-10.

McGuire, William L, and PadawcrSinger, A. "Trait Salience in the Spon

taneous Self-Concept." Journal of Per

sonality and Social Psvcltologv 3 3

( 1976): 743-754.

McGuire, William J.: McGuire,

C'laire V.; Child. Pamela; and Fujioka.

Terry. "Salience of Ethnicity in the

Spontaneous Self-Concept as a Function

of One's Ethnic Distinctivencss in the

Social Environment." Journal of Per

sonality and Social Psychology 3 6

(1978): 51 1-520.

Morse, William C. "Self Concept in

the School Setting." Childhood Educa

tion 4 1 ( 1964): 195-198.

Overly, Norman V., ed. The Unstud

ied Curriculum: Its Impact on Children.

Washington, D.C.: Association for Su

pervision and Curriculum Development,

1970.

Piers, Ellen V., and Harris, Dale B.

"Age and Other Correlates of Self-Con

cept in Children." Journal oj Educa

tional Psychology 5 5 ( 1964): 91-95.

Purkey, William W. Inviting School

Success: A Self-Concept Approach to

Teaching and Learning. Belmont, Calif.:

Wadsworth Publishing Co.. 1978.

Purkey, William W. Self-Concept and

School Achievement. F nglcwood Cliffs,

N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970.

Raths, Louis E. Meeting the Needs of

Children. Columbus, Ohio: Charles E.

Merrill Pub. Co., 1972.

Rogers, Carl R. "Toward Becoming a

Fully Functioning Person." In Perceiv

ing, Behaving, Becoming. Edited by

EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Arlhur W. Combs. Washington. DC :

Association for Supervision and Cur

riculum Development, 1962.

Rosenherg, Morris. Conceiving the

Set/. N ew York: Basic Books. 1979.

Roscnlhiil. Robert. "Teacher Expec

tation and Pupil 1 earning." In The Un

studied Cuiitculttnj. Edited by Norman

V. Overly. Washington. D.C.: Associa

tion for Supervision and Curriculum

Development. 1970.

Shavelson. Richard J : Hubncr. Ju

dith J.; and Slanlon. George G. "SelfConcept: Validation of Construct In

terpretations." R eview oj Educational

Research 4 6 (Summer 1976): 407-441.

Slavin. Robert E.. and De Vries. Don

ald L. "Learning in Teams." In Educa

tional Environment and Effects. Edited

by Herbert J. Walberg. Berkeley. Calif.:

McCutchan Publishing Corp.. 1979.

Tacco. T. Salvatore. and Bridges.

Charles M. Jr. "Mother-Child SelfConcept Transmission in Florida Model

Follow Through Participants." Wash

ington. D.C.: Office of Education

(DHEW). February 1971.

Tice. Carol H "How Will We Score

When Red. White, and Blue Turn to

Grey?: The Ultimate Accountability."

Educational Leadership 3 6 (January

1979): 2S4-286.

Wylie. Ruth. The Self-Concept: A

Critical Survey of Pertinent Research

Literature. Eincoln. Neb.: University of

Nebraska Press. 1961.

Wylie. Ruth. The Self-Concept. Vol.

2: Theory and Research on Selected

Topics. E incoln. Neb.: University of

Nebraska Press. 1979.

Yamamoto. Kaoru: Thomas. Eliza

beth C .'. a nd Karnes. Edward A. "School

Related Attitudes in Middle-School Age

Students." A merican Educational Re

search Journal 6 (1969): 191-206.

NEW!

ASCD BOOKLETS

CLINICAL

SUPERVISION

Readings on Curriculum

Implementation

Approaches to Individual

ized Education

Clinical Supervision: A State

of the Art Review

Handbook of Bask Citizen

ship Competencies

S400I6! I 80200) 48pp

Selected readings from recent

issues of Educational Leadei.

ship on problems involved in

starting and maintaining new

programs Includes summaries

of National Science Founda

tion studies of curriculum

reform in science, rruthemalics. and social studies

Jan Jeter. editoi

S475|6ll-80204)85pp

Analyzes major programs,

interprets research, and sug

gests a process for achieving

i ndrvr equalization

Cheryl Granade Sullivan

S3 75 [611-80194] S6pp

Summarizes research literature

on the origins, design,

strengths, and weaknesses of

clinical supervision

RichardC Rcm>

$4 75 (611 -80196) I 12pp

(jsts competenoes needed by

citizens and anafyzes the abili

ties required to achieve them

No. of Copies

___ Readings on Curriculum Implementation

___ Approaches to Individualized Education

___ Cllnkal Supervision: A State of the Art Review

___ Handbook of Basic Citizenship Competencies?

Enclosed is mv check pauibie ro ASCD

Please t«N me

Name _

Posuijr ,ind f-undlmq extr.l on all billed orders All orders (Ogling $20 00 or less

muM tx* prepaid try <ash. check, ex money orcJer Oder- from mynunons and

businesses must be on an official purchase Older form Discounts on orders of

[he same title to a single address 10-49 copes. 10%. 50 or. more copies 15%

Order from Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

22S No Washington St. Alexandria VA 22314

OCTOBtR 1 980

Street _

Gtv_

_ State ____ Zip -

89

Copyright © 1980 by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum

Development. All rights reserved.