The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept

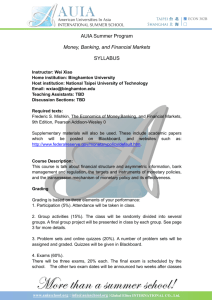

advertisement