Ch 7 Economic and Business Case Analysis

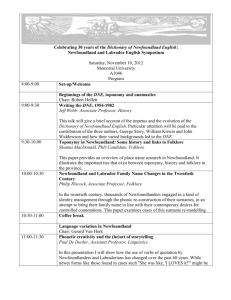

advertisement