Rising acidity

advertisement

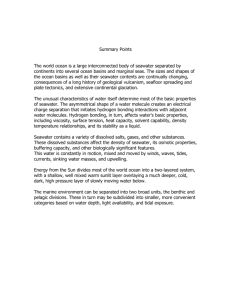

Q&A Gulf of Maine Species and dollars on the front line Answers to common questions Ocean Acidification With declining groundfish populations, approximately 80 percent of New England’s fisheries revenue now comes from shellfish. In laboratory studies, oysters, soft shell clams, bay scallops, mussels, and other shellfish reared in more acidic seawater develop more slowly, produce deformed shells, or die in greater numbers. New England’s rich maritime history also brings millions of tourists to iconic fishing communities each year. What is ocean acidification? Every day, the ocean absorbs approximately one-third of the carbon dioxide we put into the atmosphere when we burn fossil fuels and clear land. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it becomes an acid. This acid is lowering the pH of ocean water. pH is an important vital sign of ocean health, and its rapid change raises a red flag. Scientists refer to this shift in ocean chemistry as ocean acidification. Key numbers for the Gulf of Maine region © B. Guild Gillespie/www.chartingnature.com What is at risk? Second is the rank of Massachusetts among U.S. states for the value of seafood landings ($478.8 million in 2010) How might ocean acidification affect marine life? As seas become more acidic, they become inhospitable to some sea life. Rising acidity robs seawater of carbonate ions, an essential ingredient used by creatures like shellfish and corals to build their shells. In slightly more acidic water, they must expend more energy to build shells, which may leave them less able to find food or reproduce. On the extreme end, if seawater becomes acidic enough, shells literally dissolve, which can be disastrous for survival. Third is the rank of Maine among U.S. states for the value of seafood landings ($375 million in 2010) Will all sea life be negatively affected? Not all ocean organisms will be harmed by ocean acidification. We know that some creatures—corals, clams, oysters, scallops, and some forms of plankton—are sensitive to these chemical changes. More research is needed to fully understand how declines in sensitive species could ripple across the food web and cause harm to commercial finfish. © B. Guild Gillespie/www.chartingnature.com 4,500 Maine fishermen depend on one species: lobster, which could be vulnerable $13.6 billion in sales were indirectly generated by Maine’s tourism industry in 2004 How fast is ocean chemistry changing? Ocean acidification is happening faster than it has in the past 300 million years, catapulting us into unknown territory. Since the Industrial Revolution, the world’s oceans have become 30 percent more acidic, on average. Scientists predict the acidity of our oceans could double or triple by the end of the century compared to preindustrial times. For more information contact Lisa Suatoni, marine scientist, lsuatoni@nrdc.org Economic statistics were taken from: Van Voorhees, David and Lowther, Alan, “Fisheries of the United States 2010,” National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Science and Technology, August 2011, www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/st1/fus/fus10/FUS_2010.pdf Department of Marine Resources State of Maine, www.maine.gov/dmr/commercialfishing/recentlandings.htm Northeastern Regional Aquaculture Center, “2009/2010 State Situation and Outlook Reports,” www.nrac.umd.edu/publications/2009%20State%20Reports.cfm Maine Office of Tourism, Tap into Touri$m, 2006 Resource Guide, Machias: Sustainable and Experiential Tourism Workshop, March 17, 2006. Chad Coffin worries about Maine’s mudflats, which have become acidic enough in spots to kill young clams. The culprit is elevated carbon dioxide from polluted runoff and ocean acidification, a phenomenon caused by fossil fuel emissions that makes seawater more corrosive. Putting used shells back into the seafloor can buffer the acidity from this double whammy. It is like giving the ocean a Tums. But when Coffin, president of the Maine Clammers Association, asked the state legislature for needed rule changes, they wanted studies that had not yet been funded. “Ocean acidification is a deep concern, and we’re interested to see if we can add any tools in our arsenal to fight it,” said Coffin.“From what little we know, this is one of the only things we have to fight back. We need a weapon. We need to know more.” above: chad coffin digging for clams. Fully fund FOARAM The Gulf of Maine hotspot The value of information What we don’t know can hurt marine industries Why we need to be concerned Invest in FOARAM to help small businesses In 2009, Congress passed the Federal Ocean Acidification Research and Monitoring (FOARAM) Act to monitor the progression of ocean acidification and better understand how it threatens national fisheries. This important program suffers from severe underfunding, which is now stalling its implementation. Without full funding, industries that depend on robust fish and shellfish populations and vibrant coral reefs will lack basic information they need to protect their businesses. The authorized level of funding is modest in comparison to the high value of these resources. Rising carbon dioxide emissions are making the world’s oceans more acidic. In hotspots such as the Gulf of Maine’s rich and lucrative fishing grounds, local conditions make the problem worse and can accelerate the trend. Just as mariners rely on accurate weather forecasts before heading out to sea, aquaculture facilities and fishermen need to know when ocean conditions are threatening vulnerable species with elevated acidity. Two oyster hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest have suffered from massive die-offs in recent years. Scientists have determined that oyster larvae could not survive when local conditions made the seawater that hatcheries use to grow shellfish too corrosive. A $500,000 federal appropriation for a monitoring network that now measures pH, carbon dioxide, and other variables in seawater has kept the Northwest shellfish industry intact, for now. By helping oyster hatcheries identify and avoid potentially lethal water, that initial investment has provided an estimated $35 million in economic benefit to coastal communities. Yet the funds to operate this early warning system ran out at the end of 2012, and it is unclear whether money to continue the monitoring program will be appropriated. FOARAM appropriations over the last four years f y 2009 $8.0 million authorized $12.0 million authorized $5.5 million appropriated f y 2011 $15.0 million authorized $6.358 million appropriated f y 2012 $20.0 million authorized $6.206 million appropriated “There is a lot at risk for the fishing industry and anyone who eats seafood. But, as long as we have good science, we may have the opportunity to make adjustments as these changes take place Taylor Shellfish, the West Coast’s largest producer of farmed shellfish, saw its oyster production plummet by 80 percent a few summers ago. Thanks to the new equipment and favorable weather, the company has since hit record production levels. Continued inadequate funding for ocean acidification monitoring puts shellfish producers and commercial fishermen in a risky position. Puget Sound Partnership/Washington State f y 2010 Illustrations of sea life © B. Guild Gillespie/www.chartingnature.com $0.0 million appropriated over time. Without funding for science, we’ll be in the dark until it’s too late.” — m ark vinsel executive director of united fisher men of al ask a “ The monitoring equipment has literally put the headlights oyster farm samish bay, washington on the car for us. We were flying pretty blind before.” — bill dewey cl a m far mer and spokesm an for taylor shellfish