2009 Edition - Wharton Health Care Business Conference

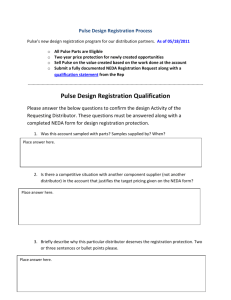

advertisement