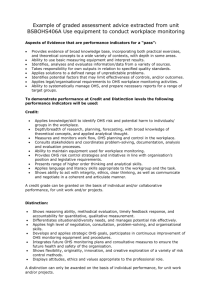

Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems

advertisement