TITLE: "The Primeval Prologue" - St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church

advertisement

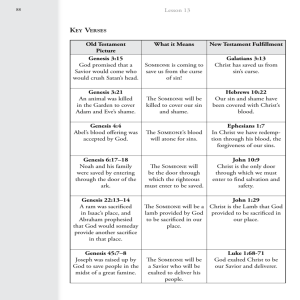

St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church January 5th, 2014 (#549a) TITLE: "The Primeval Prologue" Text: Genesis 1:1 - 11:26 Today we are beginning a yearlong adventure of sermons that will tie-in with our reading through the Bible in a year. For those of you who haven’t picked up your reading schedule yet, the whole year’s readings are available on the table in the entryway. And each Sunday I will include in the bulletin the scriptures that are to be read the following week. If you haven’t started yet, it’s not too late. Through yesterday you only had to read through Genesis 12 verse 9. Over the years I’ve used different translations as I’ve read through the Bible. This year I’m planning to use the NIV again. But whatever translation you use, listen as God begins to draw you into the biblical narratives. Be amazed once again by God’s grace - shown not only in the New Testament, but the Old Testament as well. Be with Isaiah as he is caught up into the throne room of God. Join the disciples as they hear Jesus’ words of "Do not be afraid." And as you begin your reading each day, I invite you to pray a short prayer, asking God to open your eyes and hearts to what He has for you that day. And have a pen and paper handy to write down insights and questions that have arisen during your reading and meditation. If you do that, you will find yourself on a wonderful adventure with God this year. Because of my planning for this series, I will be reading one week ahead. And as I was reading the opening pages of God’s revelation to us, I became aware once again of the pattern of humanity’s sin, God’s judgment on that sin, and also God’s grace present at the same time. Please turn with me to the first chapter of the book of Genesis, reading verses 1 through 5 before turning to Genesis 11, reading verses 1 through 9. Hear God’s unchanging Word. In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. 1 And God said, "Let there be light," and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light "day," and the darkness he called "night." And there was evening, and there was morning— the first day... Now the whole world had one language and a common speech. As men moved eastward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there. They said to each other, "Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly." They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. Then they said, "Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves and not be scattered over the face of the whole earth." But the LORD came down to see the city and the tower that the men were building. The LORD said, "If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other." So the LORD scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. That is why it was called Babel — because there the LORD confused the language of the whole world. From there the LORD scattered them over the face of the whole earth. (Genesis 1:1-5; 11:1-9; NIV) This is God’s Word. "In the beginning God..." With these few succinct words begins the biblical revelation ... a revelation that is first and foremost about God. This biblical revelation is spoken against a background of ancient stories that had their own idea of what God was like. While it is true that the ancient Mesopotamian cultures of the second millennium had produced creation stories like the Enuma Elish and flood stories like the Gilgamesh Epic, the Genesis version differs significantly in its telling. The author of Genesis deliberately challenges the Mesopotamian version of how things happened in our world. As one example, in chapter 1 verses 14 and following, the author speaks of the "greater light" and the "lesser light." Why not just call them the "sun" and the "moon"? Because the Mesopotamian culture saw the sun and moon as gods ruling the course of human affairs, and the writer of Genesis won’t dignify their understanding of that, and therefore does not even name them. The writer proclaims in no uncertain terms that it is God himself who has created these lights in the sky. Because God had chosen to reveal himself to our biblical ancestors, these men and women knew something about who this God is, and it is from that context that they write. The writer of Genesis is not interested in writing a cosmological treatise on how the world began. He is not even interested in satisfying our biological or geological curiosities. Instead, the author wants to tell the readers who this God is, and who and what human beings are - created by God, made in 2 the image of God, and yet - terribly scarred and marred by the sin which so soon entered into God’s perfect world and nearly obliterated God’s good work. It is written to convey key truths about God, humanity, and their relationship. It is a spiritual interpretation of history. It is true that Genesis doesn’t tell us everything we might like to know about the history of the universe and humanity, for much of that lies outside of God’s purpose in giving us this book. So there is no need to look into scripture to find answers to the technical questions of physics, or interstellar astronomy, or even our private musings about Tyrannosaurus Rex! What Genesis 1 does for us is tell us about the creation. It’s not the result of some biological accident. Nor does it have anything to do with some overactive amoebae deciding to crawl out of a primeval bog. Into the formless void of this "chaos" God speaks, and the world is created. God uses no building blocks - no giant Lego sets - for this creation. In fact, the writer uses a special word for "create" - "bara" - a word that is used only with God as the subject. Only God can "bara". And it is a creation "ex nihilio" - "out of nothing." Before continuing, I would like to make some comments about the structure of these writings. Genesis is the first of the beginning five books of the Old Testament - Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. Together they are called the Pentateuch, meaning "fivevolumed [book]", following the Jewish designation, "the five-fifths of the law." The Jews called it the Torah, which means "instruction." In English it has often been translated as "Law" as it is called in the New Testament. But "Law" - coming from our Western mindset - does not express the full meaning of Torah. The Pentateuch itself is divided into two parts - Genesis chapters 1 to 11, and Genesis chapter 12 through the end of Deuteronomy. The initial 11 chapters is known as the Primeval Prologue. Its focus is universal, going back to ultimate origins, and setting forth how men and women have been from ancient times: at war with themselves, alienated and separated from God and each other in a broken, disorderly world with nation against nation, individual against individual. The author paints this dark picture by tracing the origin and rise of sin from the disobedience of the first man and woman in the Garden of Eden, to the murder of Abel, the murderous vengeance expressed by Lamech, the general corruption of humanity which has become so heinous as to warrant the Flood, to the fracturing of humanity’s primal unity because of pride at the Tower of Babel - all of this darkness in contrast to the words "God saw all that he had made, and it was very good." Against this background the question is raised: What is God’s future relationship going to be with his scattered, broken, and alienated humanity? Is God’s patience going to be exhausted? 3 Will the nations experience his wrath forever? What is to become of the whole human race? Only in the light of this context can we begin to understand the significance of what follows. Immediately following the genealogy that separates the primeval and patriarchal prologues, we come upon the election and blessing of Abraham. In God’s special dealings with Abraham and his descendants - and through one particular descendant - lies the answer to the dilemma and anguish of the whole human family. As such, this juncture between chapters 11 and 12 is not only one of the most important places in the whole Old Testament but one of the most important in the whole Bible. Here in chapter 12 begins the redemptive history that awaits the proclamation of the good news of God’s redemptive act in Jesus Christ; only through him does the blessing of Abraham come to bless all the families of the earth. There are four major themes that dominate the landscape of the Primeval Prologue. First of all, there is the biblical understanding that God is the Creator, that he stands prior to and over against his creation, that all creation is dependent upon him, and that which God has created is good. It is this affirmation that prepares the way for the question of the origin of that which has disturbed this good order - sin. That brings us to the second major theme which deals with the problem of sin. In contrast to Genesis 1 which teaches the theological truth about why the world exists at all, Genesis 2 and 3 address the question of why things in our world exist as they do in a ruined condition, subject to physical and moral evil. The world was good as God made it, but mankind corrupted it by willful disobedience. The first couple aimed at being "as God" by determining for themselves what is good and bad, thereby usurping the divine prerogative. Chapters 2 and 3, then, picture men and women as above all, sinners. In the stories that follow, the author shows us the radical seriousness of sin by the sheer volume of the evidence. Once introduced into the world, sin rapidly reaches avalanche proportions. Sin not only moves in ever widening circles; it shows itself in more blatant and heinous ways. By the time we get to the story of the Flood, human sin has gotten so bad that God has no recourse but to wipe out his creatures and start all over again with Noah, who was "a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time" (6:9). 4 The author closes the Primeval Prologue with one more story, that of the Tower of Babel. The people gather together to build a city and a tower, but their purposes are motivated by a lust for fame and power: "Let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth" (11:4) Not only has sin corrupted the individual, but now it invades corporate structures and entities, which become bent on power and control. Human society now rises up in rebellion against God. This theme, which is woven throughout the stories in the prologue, speaks of the radical seriousness of the sin which, from the beginning of the rebellion of humanity, has marred and stained God’s good work. The third major theme in each of these narratives is God’s judgment on human sin. In Eden, first the serpent, then the woman, and then the man are judged by God. For each the judgment is the state in which he or she must live in the sinful, fallen condition that now characterizes our world. We note that it is only the serpent and the ground that is cursed. The man and woman are penalized due to their sin. But for humanity on its own there is no way back to fellowship with God. That way has been barred forever. Once the soil has drunk Cain’s brother’s blood, no longer will it yield to Cain its produce. And he is doomed to be a fugitive and wanderer on the face of the earth. But the supreme example of God’s judgment on human sin is the Flood story. It is probably this story, above any others, that causes some people to speak of the God of the Old Testament as a stern, demanding, and sometimes vengeful God - a very different God than the one revealed in the Gospels in the person of Jesus Christ, they tell us. Aside from the fact that these people are falling into the very same trap as our original parents - being "as God" by determining for themselves what is good and bad, thereby usurping God’s prerogative, the author seeks to express in a most graphic and terrifying way that human sin brings God’s judgment. But due to our familiarity with the story, we no longer hear it in its full force. It’s now become a delightful children’s tale of an ancient adventure. Good-hearted Noah is involved in a boat-building project on a colossal scale, light-hearted and quick-footed animals of all shapes and sizes move two-bytwo up the gangplank into the cavernous interior of the ark, and following the opening of the fountains of the deep and the windows of heaven, Noah and his floating zoo bob merrily along in safety. Meanwhile Noah’s nasty neighbours (with whom we would never identify!) sink from view. In the ancient Mesopotamian flood story, nature and the forces of nature that so deeply affected the ancients’ lives and existence were considered as divine beings. But in the biblical view, the God of Israel stood outside of nature and its forces as their Creator, and he used them as instruments of his purpose. Viewed against this background, the awesome power and terror of 5 the storm and cataclysmic destruction of the Flood are seen as the expression of God’s judgment on human sin when "every inclination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil all the time." But there is one other theme that, almost surprisingly, winds its way through the Primeval Prologue. It is the theme of God’s supporting, sustaining grace. That grace is present in and along with each judgment except the last. In the Eden story, the penalty for eating the forbidden fruit is death that very day. Yet God shows his grace in that though death is certain, it is now postponed to an unspecified time in the future. And God himself clothes the guilty couple, enabling them to live with their shame. The story of Cain does not end when the murderer cries out in despair as to his punishment. In an act of unmerited mercy, God places a mark upon him to let others know that God will protect him. And even in the supreme example of God’s judgment, we see evidences of his preserving grace. The condition which provoked God’s judgment - that "every inclination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil all the time" - becomes the grounds for God’s grace and providence "never again will I curse the ground because of man, even though every inclination of his heart is evil from childhood. And never again will I destroy all living creatures as I have done" (8:21). And that is followed up with the paradoxical measure of God’s supporting grace, known in the persistence of the natural orders despite ongoing human sin: "As long as the earth endures, seedtime and harvest, cold and heat, summer and winter, day and night will never cease." The theme of God’s supporting, sustaining grace is missing, however, at one point in the primeval account - at the very end. In the story of the Tower of Babel, there is no word of grace. With this sharp break in the primeval story, the question now rises: What is God going to do with humanity? How will he now relate to his wayward, rebellious creation? So here we stand at the point where primeval history and redemptive history dovetail. And as we continue in our reading of the biblical account, we will see that the desperate problem of human sin so poignantly portrayed in Genesis 3 through 11 will be remedied by God’s gracious action and initiative that begins with the promise to Abraham. But the redemptive history that begins there will not come to fruition until its consummation in the Son of Abraham (Matthew 1:1), the Son of Adam, the Son of God (Luke 4:38). It is his death and resurrection that will provide the ultimate victory over the sin and death that so soon had disfigured God’s good creation. AMEN. (NOTE: I am greatly indebted to Bruce Larson in his book entitled "My Creator, My Friend"; the book entitled "Old Testament Survey" by La Sor, Hubbard, and Bush; and an article in the July 6 2012 magazine "Ministry" by Randall Younker entitled "How should we interpret the opening chapters of Genesis?") 7