Simulations of the Worst

advertisement

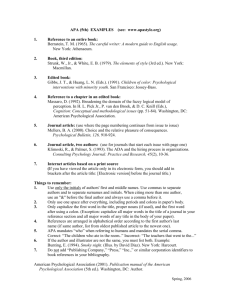

Afdeling Wetenschappelijk onderzoek en econometrie The Euro and Psychological Prices: Simulations of the Worst-Case Scenario C.K. Folkertsma Research Memorandum WO&E no. 659 June 2001 De Nederlandsche Bank THE EURO AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PRICES: Simulations of the worst-case scenario C.K. Folkertsma This paper is a translation of the Dutch Research Memorandum nr 659 'De euro en psychologische prijzen: simulaties van het worst-casescenario' by C.K. Folkertsma. Research Memorandum WO&E no. 659/0114 June 2001 De Nederlandsche Bank NV Econometric Research and Special Studies Department P.O. Box 98 1000 AB AMSTERDAM The Netherlands ABSTRACT The Euro and Psychological Prices: Simulations of the Worst-Case Scenario C.K. Folkertsma * Currently, nearly 90% of all prices of consumer goods and services in the Netherlands are psychological, conveniently broken or round prices. After converting these ‘attractive’ guilder prices into euro using the official conversion rate, the resulting euro prices are generally not attractive. The Dutch public is concerned that retailers will not round their euro prices symmetrically upwards and downwards to the next attractive pricing point but only upwards? This paper investigates the question ‘What would be the effect on the consumer price index (CPI) if prices were systematically rounded upwards’. Firstly, the attractive pricing points are determined empirically using the actual price sample underlying the Dutch CPI. Secondly, different rounding scenarios are investigated and the likelihood of the worst-case scenario is discussed. It turns out that the euro introduction may cause an increase of the CPI by 0.7% at most. However, due to competition in the retail sector, this scenario is very unlikely. Keywords: Euro, inflation, psychological prices, consumer price index JEL Codes: D49, E31, M31 SAMENVATTING De euro en psychologische prijzen: simulaties van het worst-casescenario C.K. Folkertsma Tegenwoordig zijn bijna 90% van de Nederlandse consumentenprijzen psychologische, handig gebroken of ronde bedragen. Na omrekening zullen de nieuwe europrijzen over het algemeen niet meer mooi ogen. Het Nederlandse publiek is bevreesd dat aanbieders consequent naar boven zullen afronden om mooie europrijzen te bereiken. Dit rapport geeft antwoord op de vraag: ‘Wat zou het effect op de consumentenprijsindex (CPI) zijn als alle aanbieders systematisch naar boven afronden?’ Aan de hand van de prijzensteekproef waarop de Nederlandse CPI is gebaseerd, wordt eerst empirisch bepaald welke psychologische prijzen in de praktijk worden toegepast. Vervolgens worden de prijseffecten van verschillende afrondingsscenario’s berekend. Uit deze berekeningen blijkt dat de CPI met maximaal 0,7% toeneemt, als alle aanbieders naar boven naar de volgende mooi ogende europrijs zouden afronden. Vanwege de concurrentie tussen aanbieders, waarmee bij de ramingen geen rekening werd gehouden, is dit worst-casescenario echter zeer onwaarschijnlijk. Trefwoorden: Euro, inflatie, psychologische prijzen, consumentenprijsindex JEL codes: D49, E31, M31 * Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de statistiek –CBS) supported this research by making available the necessary data. I would particularly like to thank Cecile Schut and Jan Walschots, both of the CBS, for their assistance. However, the CBS is not responsible in any way for the research method or results. Any errors are the sole responsibility of the author. -11 INTRODUCTION All products still currently priced in Dutch guilders should also carry a price in euros by 1 July 2001. A number of suppliers have already dual priced their ranges. In some cases, the transition to dual prices was combined with a sharp price increase with ‘attractive’ price points in guilders, such as NLG 1.99, being rounded up to give the product an ‘attractive’ euro price point, such as EUR 0.991. These incidents have created a suspicion among the public that all suppliers will systematically round their prices upwards and to the next attractive euro price point when the euro is introduced. Implicit in this is the assumption that price increases of such magnitude would not be happening except for the introduction of the euro and that, therefore, there are no other reasons, for example increased costs, to justify the adjustments. This study investigates the effects on the consumer price index (CPI) and the harmonised index for consumer prices (HICP) if all suppliers were to systematically round up their prices to reach attractive euro price points on conversion to the euro. This problem requires an empirical approach as the effects of such a rounding strategy on the CPI depend on the percentage of consumer expenditure in which attractive price points have a role, the prices that are regarded attractive, and the current prices and budget shares of the various goods. This study estimates the effect of rounding on the CPI by using simulations. The simulations use the same sample of prices as in the CPI for January 2001. The simulation involves determining whether or not each of the roughly 72,000 prices in the sample is at an attractive guilder price point. If the price is attractive, it is converted into euros and then rounded up to the next attractive euro price point. The remaining, ‘ordinary’ prices are converted into euros and rounded up to the next cent. The overall effect of the rounding on the CPI is computed by aggregating the price increases, weighted by the budget shares of the various products. The study deliberately pays little attention to theoretical factors such as the issue of whether there is economic justification for the expectation that the euro introduction will give suppliers an opportunity to implement profitable price increases. The simulations also ignore possible indirect effects of rounding. If the pricing strategy of retailers significantly affects the price level, compensating wage demands would prompt further price increases. This simplified approach has the advantage that it provides a clear answer to the question, ‘what would the effect be on the CPI if every supplier systematically rounds prices up?’ Naturally, the discussion of the simulation results considers the 1 In most cases, of course, the guilder price will no longer be an ‘attractive’ one after conversion. When dual pricing, suppliers are required to ensure that the two prices are accurate to the nearest cent using the official conversion rate of NLG 2.20371 per euro. -2likelihood of this worst-case scenario occurring, but for a comprehensive survey of the theoretical factors see Folkertsma and van Rooij (2001). Marketing literature divides ‘attractive’ price points into psychological, fractional and round prices. The last significant digit of a psychological price is a 9, as in NLG 1.99 or NLG 274.90. These prices are frequently used because consumers tend to ignore the last significant digit when comparing prices and do not distinguish between e.g. NLG 1.90 and NLG 1.99 but they do distinguish between NLG 1.99 and NLG 2.00 2. Fractional prices are amounts that are convenient to pay, such as NLG 2.50 or NLG 4.75. Payment of these amounts requires few coins and only one coin or none in change. These prices are often used by bars and cafés, tobacconists and public transport. Round prices are whole number amounts, such as NLG 1.00 or NLG 150.00. Round prices are used for larger amounts in particular, perhaps because a price of NLG 121.05 gives the consumer a negative impression that the supplier is tight-fisted. Since the choice of a psychological, fractional or round price depends on different motives, a supplier will not merely want to achieve some attractive euro price on conversion, but a euro price which just like the old price is psychological, fractional or round. Unlike round prices, it is not known exactly where psychological or, to a lesser extent, fractional prices lie. For example, is NLG 179.99 a psychological price, or NLG 179.00, or are both amounts relevant psychological prices? The effect on the CPI due to rounding up to psychological prices can only be reliably estimated if the psychological prices are known exactly. Since the literature provides no information on this, psychological prices are identified empirically in this study. The remainder of this report is as follows. The next section describes the data on which the simulations are based. Section 3 addresses the method of identifying psychological and fractional prices as used currently for pricing. Section 4 sets out the various rounding scenarios and the results of the simulations. It also discusses the interpretation of the simulation results. The conclusions are drawn in the fifth and final section of the report. 2 For a further description of the use of psychological prices, see Folkertsma and van Rooij (2001). -32 DATA The source material for this research is the sample of prices used by Statistics Netherlands (CBS) to compute the consumer price index (CPI) and the harmonised index for consumer prices (HICP) in January 2001 3. The data were the prices as recorded by inspectors at sales outlets. In total, the sample contained roughly 72,000 prices for 1,516 different articles selected for computing the CPI and HICP. The weighting coefficients for aggregating the price indices at item level into the CPI or HICP were also known for all articles. The effects of rounding to psychological prices have been simulated for a selection of 1,190 of the 1,516 items. Due to this selection, 132 prices from the sample were discarded. The excluded items account for some 39% and 28% of the expenditure on which the CPI and HICP are based respectively. These items have been excluded because few, if any, prices were observed for them or because psychological pricing has no role. Examples are seasonal items for which no prices were observed in January as the products, such as certain types of fruit and vegetables, garden items and summer clothing, are sold mainly in the summer. Excluded items for which the sample contained a few prices are house and garage rental, the notional rental value of owner-occupied housing, consumption taxes, TV and radio licences, subscriptions to associations and prices for goods and services such as healthcare, gas and electricity, motor fuels, telephone services, repair of household goods, insurance and road, rail and air passenger transport. These items were excluded because neither the few available prices nor the type of good and service suggests that psychological or fractional prices play any role. The excluded items represent a larger share of expenditure in the CPI than in the HICP as the coverage of the two indices varies. The main difference is that the HICP does not count the notional rental value of owner-occupied housing as consumer expenditure, although it represents over 12% of expenditure according to the definition of consumption in the CPI. 3 The CBS removed any information from the price sample which would allow the identification of the producer of the article or the point of sale. -43 IDENTIFICATION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL PRICES The results of simulating the effects of rounding on the CPI and HICP depend inter alia on the correct identification of the relevant psychological and fractional prices. If, for example, it is assumed that 0.99 is the only psychological price between 0.80 and 1.00, the conversion of NLG 1.89 into euros (EUR 0.86) and rounding up to the next psychological price (EUR 0.99) gives a price increase of 15%. If, however, 0.89 is also a psychological price, the increase would only be 3%. The correct identification of psychological prices actually in use is, therefore, crucial for the reliability of the results of the simulation. Figure 1 gives an initial impression of the prices in the sample. The chart shows the frequency distribution of the cent element in prices. It is evident that the cent elements are far from uniformly distributed and that certain figures occur very often while others are almost never used. This frequency distribution shows that all three types of attractive price points - round, fractional and psychological prices - are clearly present in the sample. Almost 24% of all prices were round. Altogether, classic psychological prices, with a 9 as the last significant digit, represented almost 31% of the observed prices. For fractional prices, the kwartje (25 cents) and multiples of it seem significant (in total, over 12% of prices). The frequency of prices ending in 95 and 98 cents (20.5%) was surprising. These twocent amounts appear to be used in the Netherlands for psychological price setting while according to the results in the theoretical and empirical marketing literature, 99 cents would be expected 4. If consumers disregard the last significant digit in prices, as suggested in the marketing literature, their purchasing decisions should be the same if prices end in 95, 98 or 99 cents. Therefore, a price ending in 99 cents should maximise profits. Moreover, a price ending in 99 cents is particularly attractive in the Netherlands, since the lowest denomination coin is 5 cents. If someone buys only a single product priced at NLG 1.99, he will actually pay NLG 2.00. However, not every price that ends for example, in 99 cents, is also a psychological price used in practice. The last significant digit in NLG 1.99 and NLG 107.99 is a 9 and so is regarded as psychological in the literature, but NLG 107.99 did not occur at all in the sample. The exact location of actual psychological price points cannot, however, be derived directly from the distribution of prices. This is illustrated by Figure 2, which presents the frequency of individual prices in the sample 5. 4 For a survey of the relevant literature, see Folkertsma and van Rooij (2001). 5 The sample of 71,757 observations included 5,566 separate prices. -5Figure 1 Frequency distribution of the cent element in prices Figure 2 Frequency distribution of prices -6The chart shows that some prices occur far more frequently than others do, while many amounts were not observed at all. It appears that the greater the price, the greater the distance between individual prices. For example, as many separate prices were observed between NLG 0 and NLG 7 as between NLG 39 and NLG 81. In general, the frequency with which prices were observed between NLG 0 and NLG 7 was higher than the frequency of the relatively common prices between NLG 326 and NLG 482. The actual psychological price points in use were identified for the simulations in a two-stage procedure. Firstly, all significant prices were identified by means of a rolling 75% percentile and they were then classified as psychological or fractional prices. In the first stage, the 75% percentile was computed for the distribution of the number of observations for each 100 consecutive prices in the sample. If the median of the 100 prices considered was among the 25% most observed prices, it is considered a significant price. This approach is rolling as the selection procedure is repeated, starting with the 100 lowest prices, then the next 100 prices with an overlap of 99 prices and so on. The number of observations necessary to be identified as a significant price in this sample is set out in Figure 3 for prices up to NLG 50. The decision to use the 75% percentile for 100 consecutive prices is motivated for purely empirical reasons. A higher percentile would have resulted in fewer prices being selected and relevant psychological prices possibly being ignored. If the 75% percentile is based on more than 100 consecutive prices, the curve of the percentile as a function of the price would be smoother than in Figure 3, in which case, the percentile reacts less quickly to changes in the number of observations that is normal for the neighbouring prices. Here too there is a risk that a figure, which is actually used for setting psychological prices, would not be recognised as such. The selected combination of a 75% percentile and 100 consecutive prices means that a large number of prices which is classified as significant can also be interpreted as either psychological or fractional. The second stage in identifying psychological prices is classifying significant prices as psychological or fractional prices. If the last significant digit of an observed significant price was a 9 or if it ended in 98 or 95 cents, it was regarded as a psychological price. If any of the remaining prices were divisible by 5 cents, they were classified as fractional prices. Prices not falling into either of these two categories were ignored. Although, according to the literature, prices ending in 95 or 98 cents should be in the ordinary price category, they are used by Dutch businesses as psychological prices and this explains the frequency distribution of the cent elements (Figure 1) and the regularity with which our selection method identified these prices. -7Figure 3 Rolling 75% percentile Of the total of 5,566 different prices in the sample, 1,799 were significant and, of them, 624 were psychological and 978 were fractional prices according to the listed criteria, while 197 prices proved to be neither psychological nor fractional, e.g. NLG 6.57 6. The method used here to determine psychological and fractional prices fails for the highest and lowest prices. The simulations, however, are not influenced by the absence of the highest psychological or fractional prices as converting the highest guilder prices into euros gives amounts that are 55% smaller. The lowest psychological prices that are relevant for the simulations were extrapolated. The prices 0.09, 0.19, 0.29, 0.39, 0.49, 0.59, 0.69, 0.79 and 0.89 were also regarded as psychological as they are also used for psychological pricing with NLG 1, 2 and 3. The smallest fractional prices were constructed rather than extrapolated. The assumption for the construction is that a supplier uses a fractional price so that payment is quick and simple. Setting a price which can be paid using one, two or three coins and which requires no change or only one coin in change, ensures simple and quick payment. In principle, the price effects of the euro introduction can be simulated by applying this set of psychological and fractional prices as used by Dutch businesses. There are, however, three problems. Firstly, it is not certain that the set of psychological prices is complete since the source material is a 6 The appendix shows the prices thus identified between NLG 0 and NLG 25. -8sample of prices and significant prices have been selected by using a heuristic method. Missing psychological prices could considerably distort the results of the simulation, especially on the conversion of low prices. Secondly, amounts that are easy to pay depend on the available denominations. For example, payment of 0.75 cents in guilders requires three kwartjes or one guilder with one kwartje change. This is a simple payment. In contrast, the payment of the same figure in euros requires more than three coins. Therefore, it is not considered a simple payment. Finally, round prices have been ignored up to now. Prices such as NLG 5.00 or NLG 125.00 can be seen as either fractional or round. The results of the simulation would be distorted if a supplier deliberately set a round price for a product, which was treated as a fractional price in the simulation. As fractional prices, NLG 5.00 and NLG 125.00 would become EUR 2.28 and EUR 56.80 respectively and not EUR 3.00 and EUR 57.00 respectively. There is no general solution for the first problem. In order to limit the distortion of the simulation, it seems reasonable to assume, in any event for amounts under NLG 10 that all prices ending in 9 cents are in principle psychological prices. Under this hypothesis, there are 19 more psychological prices in addition to those identified empirically 7. A solution for the second problem could be to construct all fractional prices in guilders and euros. In this approach, only empirical psychological prices would be used in the simulation while all empirical fractional prices would be replaced by constructed fractional prices. Theoretical fractional guilder prices could be used to determine whether a price in the sample is fractional or not, while the theoretical fractional euro prices could be used for rounding converted prices. The construction of the fractional prices was based on the same principle for the two currencies; i.e. that fractional prices should make payment simple. A payment is simple if it can be made with three or fewer coins or banknotes with no change or only one coin or note being needed for change. The third problem can only partly be solved, as it is not clear whether say NLG 7.00 was chosen as a round figure or for simplicity of payment. A partial solution is to regard all round prices, and not only round prices which are also classified as fractional, above a given threshold as being rounded to a higher round euro price. The threshold should be selected so that above it the cents are an insignificant part of the price. In most of the simulations, NLG 25 was taken as the threshold. This amount is very low so that figures are probably rounded to a round price too often. This implies that the simulation will more likely overestimate than underestimate the price effect. 7 The appendix shows empirical psychological and fractional prices up to NLG 25. The table also shows the 19 prices, which have been added to the set of empirical psychological prices. -9Table 1 sets out the percentage of the observed prices which, according to the main definitions, are regarded as psychological, fractional or round. According to the criteria used, almost 90% of the prices in the sample were psychological or fractional. However, these figures overstate the significance of psychological and fractional prices in household consumer expenditure. The final column in the table shows that less than 50% of total expenditure is on goods and services with psychological or fractional prices. Table 1 Percentage coverage for different definitions of psychological, fractional and round prices Description Coverage _______________________ unweighted a) weighted b) ________________ ___________________________________________ ___________ __________ 1. Empirical All significant prices which are psychological or 88.2% 46.0% psychological and fractional. Extrapolated psychological and constructed fractional prices fractional prices for amounts under NLG 0.95. 2. Empirical psychological and constructed fractional prices Psychological prices as in 1, including 19 additional psychological prices between NLG 1 and 10. All fractional prices are constructed. 86.5% 44.7% 3. Including round prices As 2, but including all round prices above NLG 25. 89.6% 49.4% a) as a percentage of the 71,757 observed prices; b) percentage of the observed prices per item, aggregated using the CPI weighting coefficients. - 10 4 ROUNDING SCENARIOS AND SIMULATION RESULTS The principal aim of this research is to determine the size of the maximum effect on the CPI if all suppliers were to systematically round their prices upwards to psychological, fractional or round prices on the introduction of the euro. The upper limit of the price effect is quantified using simulations. The following assumptions are used for the simulations. Firstly, all suppliers choose psychological, fractional, round or ‘ordinary’ prices for their products and keep the price of each product in the same category after repricing in euros. Secondly, suppliers systematically round upwards. In other words, if a product has a psychological, fractional or round price and the price after conversion into euros is not in the same category, the supplier always rounds the price to the next highest psychological, fractional or round price respectively. Ordinary prices are also consistently rounded upwards, for example, NLG 1.17 (EUR 0.5309) becomes EUR 0.54. Thirdly, it is assumed that the psychological price points do not change as a result of the introduction of the euro. If NLG 1.89 is a psychological price, then EUR 1.89 is also a psychological price. This assumption applies for psychological and of course for round prices, but not for fractional prices, as these depend on the denominations of coins and banknotes. Fourthly, it is assumed that, when setting prices, the supplier does not allow for the fact that the new prices could affect the demand for his product because his market share compared with his competitors changes or because the market volume varies. Finally, indirect price effects, which could be the consequence of say a wage-price spiral, are ignored. The results of the simulation depend on how psychological, fractional, round and ordinary prices are defined. The maximum effect on the CPI has been computed using four different definitions. − In Scenario 1, a distinction is only made between psychological, fractional and round prices on the one hand and ordinary prices on the other. Furthermore, all pricing points have been determined empirically. In other words, in this simulation, NLG 2.69 (EUR 1.22) is rounded to EUR 1.25 and NLG 5.00 (EUR 2.27) to EUR 2.29. This simulation shows the maximum effect on the CPI if the distinction between psychological, fractional and round prices is irrelevant. − In Scenario 2, a distinction is drawn between psychological and fractional prices, and empirical psychological and fractional prices are used to determine whether the product has currently a psychological or fractional price. In contrast, empirical psychological and constructed fractional euro prices are used for the rounding of the euro prices. This scenario involves on the one hand taking as much account as possible of prices with a major empirical significance and on the other hand the special role that convenient, fractional prices play and the fact that these prices depend on denominations. - 11 − Scenario 3 also differentiates between psychological and fractional prices, but allows theoretical considerations to play a larger role. Theoretical psychological prices are added to the empirical psychological prices for amounts below NLG 10 and constructed amounts are applied for both currencies for fractional prices. − Scenario 4 is the most comprehensive as it also allows a separate role for round amounts. This scenario is the same as Scenario 3, except that all prices above NLG 25, which are round but not psychological, are rounded to a round euro price. For comparison, two alternative computations are also made. Scenario 5 shows the price effect if Scenario 4 were applied but all suppliers round up and down symmetrically. Rounding up to the higher psychological price is done if the relative price increase is smaller than the relative price reduction to the nearest lower psychological price. Finally, Scenario 6 shows the effects of deciding whether the pricing of an item is psychological or fractional for the item as a whole rather than for each of its separate prices. The scenario is the same as Scenario 4, except that if more than 5 prices are observed for an item and more than 75% of those prices are either psychological or fractional, all the prices of that item are rounded up to psychological or fractional euro prices respectively. The computation of the effects on the CPI uses the same index formula underlying the Dutch CPI. The Dutch CPI is a Laspeyres price index, which can be written as a weighted average of price indices per cpit = ∑ wi Pti i item in which wi is the share of item i in total consumer expenditure in the base period and Pti is the price index of item i at time t compared with the base period 8. In the Netherlands, the price index per item Pti is defined as the unweighted arithmetic mean of the observed prices for item i in period t divided by the corresponding mean for the base period. The simulation used the same weighting coefficients as the current CPI/HICP (base year 1995) while the precisely converted euro prices in the sample (January 2001) served as base prices. The results of the simulations for the various scenarios are set out in Table 2. Table 2 shows that the Dutch CPI will rise by 0.7 % if all suppliers round their prices upwards on the introduction of the euro to reach psychological, fractional or round euro prices. As a result of the 8 If the budget shares of homogenous and exactly identified products are known, w = i p0 i x0 i ∑p j xti is the amount of product i bought in period t and pti is the corresponding price. 0j x0 j and Pti = pti p0 i in which - 12 Table 2 Price effects on the CPI and HICP in the different scenarios (%) CPI HICP __________________________________ __________________________________ Total Psychological Fractional Ordinary Total Psychological Fractional Ordinary ____ ___________ ________ _______ ____ ____________ ________ _______ Scenario 1 0.53 0.52 0.01 0.63 0.62 0.01 Scenario 2 0.74 0.63 0.10 0.01 0.87 0.73 0.12 0.01 Scenario 3 0.71 0.61 0.09 0.01 0.84 0.71 0.12 0.01 Scenario 4 0.74 0.61 0.13 0.01 0.88 0.71 0.16 0.01 Scenario 5 -0.04 -0.04 -0.01 0.00 -0.05 -0.05 -0.01 0.00 Scenario 6 0.73 0.62 0.11 0.01 0.86 0.72 0.13 0.01 Notes: Rounding effects occurring with round prices were combined with the rounding for fractional prices. The results of the benchmark scenario are in bold type. The table reports the total price effect and its breakdown in the effect due to rounding towards psychological and fractional prices as well as due to rounding towards whole cents. different coverage, the effect on the HICP is 0.2 percentage points higher. There is no significant effect on the CPI if suppliers round up and down symmetrically and this is the, in itself, unsurprising result of Scenario 5. It is notable that the upper limit of 0.7 % for the CPI is robust with respect to the scenarios underlying the simulations. It is virtually irrelevant if the pricing strategy is determined for individual prices (Scenarios 1-4) or whole items (Scenario 6). It also makes no difference if purely empirical psychological and fractional prices are used or if theoretical considerations have a role in determining these prices (Scenarios 2 and 3). Finally, it is of minor significance if round prices have a special role in price setting (Scenarios 3 and 4) in addition to psychological and fractional prices. This result is surprising, as almost 24% of the observed prices were round amounts. A significantly lower maximum effect on the CPI only occurs if suppliers do not differentiate between fractional prices and psychological prices but simply regard both categories as psychological, as in this case the distance between two psychological prices is considerably less and so the amount of the rounding falls. The benchmark scenario, Scenario 4, is the most comprehensive from a theoretical perspective. It reflects the separate roles of psychological, fractional and round prices in price setting, it allows for the different denominations of the euro and the guilder and is based on the empirical psychological prices with additional theoretical prices for amounts up to NLG 10. Although the maximum effect on the CPI in this scenario is 0.7 %, prices rose on average by 1.5%, when the unweighted average of the 1,190 items for which psychological price setting played a role is involved. For some items, in particular those with low prices, prices could go up by more than 10% (see Figure 4). - 13 Figure 4 Accumulated price effects per item in the benchmark scenario It is unlikely that the CPI/HICP will go up by the figure estimated here if there are no other costrelated reasons for suppliers to raise their prices. Apart from costs businesses incur to make themselves euro compliant, however, these causes of price increases have nothing to do with the introduction of the euro. The worst-case scenario, in which all businesses consistently round their prices up to attractive euro price points and in the absence of any other reason for price increases to improve their margins, is unlikely. Why should businesses wait with price increases until the introduction of the euro if their competitive position and market conditions allow profitable price increases now? Menu costs, in other words the cost of changing the price of a product and applying the new price information, could be a reason why businesses have not implemented profitable price increases earlier. Changing prices and applying new price information is costly. As the introduction of the euro requires the price information on every product to be altered anyway, that moment may be used by businesses to implement price increases which were postponed due to menu costs or which were otherwise planned for the near future. This argument is not convincing, however. The average (unweighted) price increase in the benchmark scenario was 1.5% and price changes of between 2 and 6% were not exceptional. Empirical estimates of the amount of menu costs indicate much smaller figures. Consequently, it is unlikely that menu costs could explain why suppliers would systematically round upwards on the introduction of the euro. - 14 A second possible reason for choosing the introduction of the euro as the time to make profit-raising price increases is implicit price arrangements: if every supplier thinks that all competitors will round up, it could also be the best strategy for him to consistently round his own prices upwards. This argument is also unconvincing because the resulting situation will not be an equilibrium. Firstly any supplier could increase his market share and profit by not systematically rounding up prices, in contrast to the competitors. Thus, each retailer has a strong incentive to defect from an implicit price arrangement. Secondly, it is not correct to assume that consistent rounding up of prices would leave the market shares of the various suppliers unaffected. Hence even if no retailer would defect, the initial situation would not constitute an equilibrium. This can be demonstrated by the following example: say that a product is offered in three shops at NLG 1.89, NLG 1.95 and NLG 1.99. Compared with the cheapest shop, the price differences for the other two suppliers are 3.2% and 5.3% respectively. If all three shops act in accordance with the assumptions underlying the simulations, after the introduction of the euro the product will cost EUR 0.89 in the first and second shops (price increases of 3.8% and 1% respectively) and EUR 0.99 in the third shop (price increase of 9.6%). Compared with the cheapest shop, this cuts the price difference to 0% at the second shop and increases it to 11.2% at the third shop. This change in the relative prices between substitutable products or the same product in different shops will affect the market shares of the product and the shops. Using the simulations, it can be shown that this example is not exceptional. The data underlying the simulations are the observed prices for 1,190 different items. The various products that the CBS has combined into one item are very similar and are probably good substitutes from the consumer’s perspective. The standard deviation and the distance between the 25% and 75% percentiles (interquartile range) of the logarithmic prices are two measures for the spread of the relative prices. If these measures are greater for the actual prices than for the rounded euro prices, consumers will have less reason to buy the product from cheaper suppliers after the introduction of the euro. If, however, relative price differences increase, more consumers will go to discounters. In the first case the market share of the cheaper supplier will probably fall, while in the second case it will rise. Figures 5 and 6 show how the standard deviation and interquartile range of the logarithmic prices per item move when the change is made from the guilder to the euro according to Scenario 4. These charts clearly show that an implicit price arrangement between suppliers to consistently round upwards to reach attractive euro price points will significantly affect relative price differences. This will not be without consequences for market shares. If a supplier wishes to avoid losing market share, he will choose a less inflationary approach to rounding. - 15 Figure 5 Change of standard deviation of logarithmic prices in relation to relative price increases per item Figure 6 Change of the interquartile range of logarithmic prices in relation to relative price increases per item - 16 - Based on the competition between suppliers and the fact that rounding on the introduction of the euro does not lend itself to implicit price arrangements, the simulations presented here are a worst-case scenario that is unlikely to occur. In addition to these economic arguments, there is also a more technical reason why the results of the simulation overestimate possible price effects and so form an upper limit for the expected effect on the CPI. The empirical method has almost certainly not identified every psychological price that is used in practice. For example, according to the sample of prices and the method used here to identify psychological prices, there is no psychological price point between 74.95 and 79.00. This means that a price of NLG 169.00 (which is psychological) will be rounded from EUR 76.69 to EUR 79. This price increase of 3% overestimates the actual price increase if there are psychological prices between 76.69 and 79.00, such as NLG 76.95. Note that 0.28% of the observed prices were NLG 169. Finally, it has been checked whether the simulations could underestimate the price effect because a significant proportion of prices had been rounded before January 2001 to attractive euro amounts. As this was the time when the sample of prices that underlay the simulations was taken, the simulation would only provide information on the maximum price effect of euro repricing at the remaining suppliers. A survey of cash-handling organisations held by the Bank in March showed that 35% of those interviewed had already dual-priced their products. A check of whether the exact euro prices in the sample were psychological or fractional prices showed that this was the case in less than 0.9% of the prices. This small percentage barely detracts from the representativeness of the simulated effects. Furthermore, it is probable that this percentage is an overestimate as, for example, NLG 19.59 was not identified empirically as a psychological price but NLG 8.89 was. Since NLG 19.59 converts precisely to EUR 8.89, all products, which cost NLG 19.59 appear as if their pric e was already rounded to an attractive euro amount. It is, however, just as likely that NLG 19.59 is a psychological price, which was not classified as such by the identification method. - 17 5 CONCLUSIONS Incidents have raised the suspicion among the public that the introduction of the euro could lead to a general increase in prices. Suppliers will consistently round up prices on conversion so that their euro prices are psychological, fractional or round. This simulation study investigated the maximum effect on the CPI and the HICP if all suppliers actually chose this repricing strategy. Based on the sample of prices, which also underlay the computation of the CPI in January 2001, it can be concluded that the CPI will increase by a maximum of 0.7 %, although a few products could increase in price by 10% or more. Account has been taken of a large number of factors, which could influence price setting. Firstly, only psychological prices were used that are actually applied in practice. Secondly, account was taken of the fact that the choice of psychological, round or fractional prices is determined by different motives and that the converted euro price would be of the same type as the original price in guilder. Thirdly, the influence of the different denominations of guilders and euros on fractional prices was incorporated. However, the simulations, completely ignored whether competitive conditions permit systematic rounding up. The discussion of the simulation results showed that neither menu costs nor implicit price arrangements between suppliers could support the view that the introduction of the euro leads to profit-raising price increases. If there are no reasons other than the introduction of the euro for changing prices, an increase in the CPI by as much as 0.7% is, therefore, unlikely. - 18 BIBLIOGRAPHY Folkertsma, C.K. and M.C.J. van Rooij, 2001, De invloed van de euro-invoering op de prijzen. Deel I: een verkenning op basis van de literatuur, Research report WO&E No. 654, De Nederlandsche Bank nv. - 19 - APPENDIX Empirical psychological and fractional prices to NLG 25 0.05 0.09 0.10 0.15 0.19 0.20 0.25 0.29 0.30 0.35 0.39 0.40 0.45 0.49 0.50 0.55 0.59 0.60 0.69 0.75 0.79 0.89 0.90 0.95 0.98 0.99 1.00 1.05 1.09 2.00 1.15 1.19 2.15 2.19 2.09 3.00 3.05 3.09 4.00 4.09 5.00 5.05 5.09 6.00 6.05 6.09 7.00 8.00 9.00 10.00 11.00 12.00 13.00 14.00 15.00 16.00 17.00 18.00 19.00 20.00 21.00 22.00 7.09 8.09 9.09 23.00 24.00 10.10 3.19 4.19 5.19 6.19 7.19 8.19 11.15 9.19 10.19 11.19 13.19 16.19 15.20 1.25 1.29 2.25 2.29 3.25 3.29 4.25 4.29 5.25 5.29 6.25 6.29 7.25 7.29 8.25 8.29 9.25 10.25 11.25 9.29 11.29 13.25 14.25 13.29 16.25 17.25 19.25 20.25 21.25 20.29 23.29 16.30 24.30 1.35 1.39 2.35 2.39 23.35 3.39 4.39 5.29 6.39 7.29 8.29 9.29 1.45 1.49 1.50 1.55 1.59 2.45 2.49 2.50 2.55 2.59 3.45 3.49 3.50 3.55 3.59 4.49 4.50 4.55 4.59 5.49 5.50 6.49 6.50 7.49 7.50 8.49 8.50 15.45 9.49 10.49 11.49 12.49 13.49 15.49 16.49 17.49 18.49 19.49 20.49 21.49 22.49 9.50 10.50 11.50 12.50 13.50 14.50 15.50 16.50 17.50 18.50 19.50 20.50 21.50 22.50 5.59 6.59 7.59 8.59 8.60 1.65 1.69 1.75 1.79 1.80 1.85 1.89 2.65 2.69 2.75 2.79 2.89 3.89 4.89 1.95 1.98 1.99 2.95 2.98 2.99 3.95 3.98 3.99 4.95 4.98 4.99 3.69 3.75 3.79 4.69 4.75 4.79 5.69 5.75 5.79 5.89 5.90 5.95 5.98 5.99 6.69 6.75 6.79 6.89 6.95 6.98 6.99 7.69 7.75 7.79 8.89 7.90 7.95 7.98 7.99 8.69 8.75 8.79 8.89 8.90 8.95 8.98 8.99 15.39 9.59 23.45 23.50 24.50 15.59 10.60 17.65 19.65 9.69 11.69 12.65 15.69 9.75 10.75 12.75 13.75 14.75 15.75 16.75 17.75 18.75 19.75 9.79 19.80 11.85 9.89 9.90 11.90 12.90 13.90 14.90 15.90 16.90 17.90 18.90 19.90 9.95 10.95 11.95 12.95 13.95 14.95 15.95 16.95 17.95 18.95 19.95 9.98 10.98 11.98 12.98 13.98 14.98 15.98 16.98 17.98 19.98 9.99 10.99 11.99 12.99 13.99 14.99 15.99 16.99 17.99 18.99 19.99 21.75 21.79 20.80 21.80 20.85 23.75 20.90 21.90 22.90 20.95 21.95 22.95 20.98 20.99 21.99 22.99 23.90 24.90 23.95 24.95 24.80 23.99 24.99 Notes: The above amounts are the observed psychological and fractional prices. The underlined prices are regarded as psychological, the others as fractional. The psychological and fractional prices in italics in the first column were extrapolated or constructed respectively. The additions to the empirical psychological prices in Scenarios 4 to 6 are shaded in grey.