Adventures in the Last Great American Wilderness

advertisement

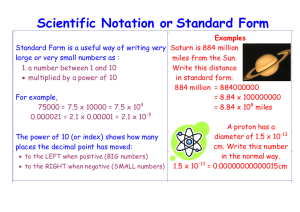

d n u o B Yukon By: William “Dots” Loopesko t s a L e h t n i s e r u Advent s s e n r e d l i W n a c i Great Amer Is it even morning? It’s hard to know when it’s sunny all the time. Rusty’s still asleep next to me even though it feels like a solar oven in here. As I emerge sweaty from the tent, I feel the hot Alaskan sun on my face and notice that it’s another dry and cloudless day. I glance over to where the food was stored and am relieved, as usual, to see that the bears didn’t get it while we slept. Before I allow the day to begin, I go to the edge of the sand bar we slept on and jump into the warm seventy degree water to wash the sweat off. Five minutes later, as I’m preparing breakfast Rusty, my traveling companion, emerges from the tent and starts packing our gear up. July 4th 2009, day 27 of our Yukon River through-paddling expedition, is going to be another exciting day. Though we left mining country a week ago, it’s hard not to think about how those thousands of prospectors must have felt as they braved this wild country looking for riches. Gold was discovered on the Klondike River in 1897. The rush was on. Nearly 30,000 people, the largest mass migration of humans in history, made the trek over the snowy Chilkoot Pass during the winter of 1897-98 and down the river come ice out. Though very few found gold, and far fewer stayed more than a few years, the relics and legacy they left behind have left a profound impact on the Yukon Territory and made it world famous as a place that favors the bold and adventurous. Following in the path of these adventurous men is one of the many reasons we’ve come to spend our summer in this great northern wilderness. The Yukon River is anywhere between 1,750 and over 2,000 miles long depending on how you define the exact beginning of the river among the plethora of alpine lakes, tributaries and glaciers in the mountains from which it flows. Historically the river began at Bennett, British Columbia, the abandoned ghost town at the head of Bennett Lake and the end of the Chilkoot Trail. It was here that most of the prospectors spent the harsh winter of 1897-98 and in the spring launched their handmade boats in which they carried all their hopes and dreams. It was here that we began our own journey 111 years later, full of all of the expectations and anxieties inherent in embarking on the longest trip either of us had ever been on. Little is left of this once bustling boomtown, but its spectacular scenery and historic significance has made it an important stop on the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad which was built for the prospectors but now carries tourists seeking to experience the thrill of the gold rush in comfort and luxury. We were quite a sight with all of our gear and canoe as we boarded the train full of seniors and families on vacation. The whole train provided us with words of encouragement, and once there, they all came down to the beach to see us off. We packed all of gear into the boat, thanked everyone for their kindness and pushed off into the icy waters. Our adventure had begun. Since that day nearly four weeks ago we’ve paddled over 1,100 miles of spectacularly untouched wilderness. It’s become clear that, regardless of its exact length, it’s hard to argue that the river is anything but powerful and huge. For its first seven hundred miles, the river rushed us through rugged mountains with a speed that was thrilling, sometimes terrifying and boosted our confidence in our paddling strength by allowing us to average over 50 mile a day. A week ago, the mountains ended very abruptly and we entered an impossibly vast wilderness of water, sand, forest and sky. The Yukon Flats is the largest swamp on the continent and over the course of 250 miles through these wetlands, the river has swelled to a width of nearly ten miles and become so braided and choked with islands sand bars that it has rendered all of our navigational equipment completely ineffective. For the last week we’ve had only the current as our guide and the thought that we might be stuck in this maze forever was never too far away. While the Yukon Flats certainly don’t possess the more obviously spectacular beauty of the mountains which surround them, in traversing them we’ve been able to experience their more subtle splendor. Cloudless blue skies stretch out to endless horizons, myriad birds swarm around our canoe and save the very occasional skiff, our only companions have been the 24 hour sunshine, the wind, the birds, and the river’s current, gently carrying us towards our destination. The silence and isolation here are palpable, and on more than one occasion we’ve heard the islands speaking to us, echoes of the conversation in the canoe. ns...” “Cloudless horizo s s le d n e o t t u o h blue skies stretc The idea for this trip was formulated by Rusty and me nearly a year ago at the start of our junior year at Bates College. Our primary objective was the Phillip J. Otis Fellowship, the college’s highly sought after adventure grant which provides money to explore the connections between nature and society. Though neither of us were particularly accomplished paddlers, we had settled on canoeing as our means of transportation since it would be easier to convince the selection committee that we needed to earn this grant together. After dozens of discarded ideas, we settled on the Yukon River since it possessed the perfect blend of history, wilderness, scenery and culture. During the nine-month application and then preparation process we researched every aspect of the river, culture and history of Alaska and Northern Canada. We wanted to be ready. For the last week, we’ve been teased by the presence of hazy mountains on the horizon, but only yesterday did we begin to notice them approaching. Last night we slept at the foot of the mountains, near the point where the river’s many meanders find each other and reunite to form a single, wide channel which punches through the Fort Hamlin Hills. Within less than five miles the river’s character changes dramatically from flat broad swamp to narrow rugged canyon and, as we go around the first bend, the Flats disappear from sight and become another memory to be tucked away and treasured. Already we have so many, and the trip’s barely half over. On “...we were traversin g through the land o f far more grizzlies th an humans...” the distant shoreline we a see a dark spot that appears to be moving and as we paddle over we see a small black bear walking the shore alone, only the second one we’ve seen in our time on the river. During the six days of near constant driving between Maine and the Yukon Territory, the one of us not driving would read aloud to the other the bear book. The bear book was a several hundred page long saga depicting savage bear attacks and ways in which to avoid becoming a victim of one. While reading about ferocious grizzlies eating their helpless victims’ faces, we had to repeatedly reassure ourselves that despite the fact that we were traversing through the land of far more grizzlies than humans, our preparations hopefully assured us this would likely not be our fate. We were going to sleep on islands each night, we were committed to keeping a clean camp and we had a gun. Despite our apprehensions, the Otis Committee and our parents had insisted that we get one. Bears were our biggest unknown, the one thing that would most keep our mothers up at night, the thing that we’d be least able to control yet would constantly be our most terrifying threat. However, despite the lingering fear of these “monsters”, their presence was titillating. Bears represented the essence of the wilderness we had come so far to experience, of a place where nature is still completely in control, and man is but a temporary and fragile guest. To spend time in bear country was to commune with the essence of untamed wilderness, and to be forced to respect it lest it turn on us. Now as I watch this bear not as a monster, but rather as the beautiful and powerful creature it is I’m forced to ask myself, could I shoot this creature? I try to reassure myself that I could at a time when I might have to, but uncertainties remain. Let’s never find out. In its simplest sense, the bridge is just a piece of the Dalton Highway, which spans the river on its way to the Arctic Ocean. To us the bridge is so much more. The bridge is the last connected road to touch the Yukon River. For the next 800 miles, the villages we’ll encounter are completely self sufficient. As the human population increases past the bridge, so too will river traffic as the river becomes the primary mode of transportation. Getting out becomes much harder, and far more expensive. The river becomes larger, and far more temperamental. The weather grows colder. Many travelers on the Yukon stop at the bridge, preferring the convenience of pulling out at a place connected to civilization. As the bridge fades out of sight behind us we’ve committed ourselves to completing our trip. In 800 miles we’ll be at the Bering Sea. We’d purchased our fireworks in Minnesota, during the drive, and kept them with us through all those miles for this moment, our own little 4th of July celebration. We’re camped tonight on a small sandbar at the bottom of a very deep and narrow canyon. The high alpine peaks above us are aglow in the midnight sunshine. After the desolation of the flats, the few fish camps we passed camps earlier, some with people sitting out on the porch drinking beers, made this canyon seem civilized. As the crackling of the fireworks echo off the canyon walls, we wonder if someone might actually be able to hear us now. After singing the national anthem and firing off a few more fireworks we retire back to the driftwood camp fire and eventually to bed. The only sound outside is the wind ruffling the tent. Could it be bring- ring?...” orrow b m to l il w s e r tu n e v d “What a ing in some weather? Day 27 was a great day. What adventures will tomorrow bring? More than a month later, Rusty and I are standing at the top of the Chilkoot Pass, on the snowfield which melts into the lake out of which one of the many small streams that form the Yukon flows. The last few weeks have been a blur of excitement and adventures that I can only hint at. Ten days ago we had reached the Bering Sea, more than one week ahead of schedule. As we stood at the edge of a landmass, scanning the horizon for any signs of Russia, we reflected back on the miles and memories that had brought us to this point. There was the all night paddle through the featureless expanse of the delta, that one time we spotted a “cool looking mountain” and climbed to the top of it, the wonderful people we’d met along the way, the silence and the conversations that had filled it, the vast and empty horizons, the spectacular scenery, the endless sunshine, and the countless hours spent soaking it all in. Life hadn’t always peaches and cream (to use Rusty’s expression). There had been that one time we almost got struck by lightning, the sudden squalls, the rainy days and the relentless headwinds. But life had been reduced to its most primitive and basic elements. We had been completely free from all the confines and pressures of society in a way that few people these days can ever be. We’d hadn’t just lived, we’d experienced. Edward Abbey once said, “Wilderness is not a luxury, but a necessity of the human soul” and after this trip I had to agree. Now after the end of our trip, our voyage has come full circle. For prospectors, this point represented only the beginning of their journey, and looking at the enormity and ruggedness of the landscape that lies below me, I can now begin to imagine what shape that journey must have taken, and why these people undertook this perilous and unknown journey. Though gold had been the official reason, most knew they would never find it, and instead had gone up north seeking adventure, comradery, and escape. Though 111 years had passed since those brave miners crossed these mountains our reasons for coming here hadn’t change. The gold they had found wasn’t shiny, but instead took the form of the friendships that had formed, maintained and solidified, the experiences that had been gained and the memories that had been formed and that they would undoubtedly cherish forever. 111 years later were lucky enough to also find that the same gold was still left on the Yukon River. -Dots Loopesko ‘09